Los Angeles (AP) – David Attenborough, who turned 90 last Sunday, isn’t resting on his laurels or any other element of the natural world he’s explored so fully.

The man behind acclaimed documentaries including “Life on Earth” and “The Life of Birds” is giving insects their TV close-up in the three-part “Micro Monsters with David Attenborough”.

He will reprise his role as narrator for “Planet Earth II,” the BBC’s recently announced sequel to the awe-inspiring 2006 project. And he brushes aside any notion that his curiosity or drive might flag after more than 100 films and series (as producer, writer or presenter, and at times all three) and some 25 books.

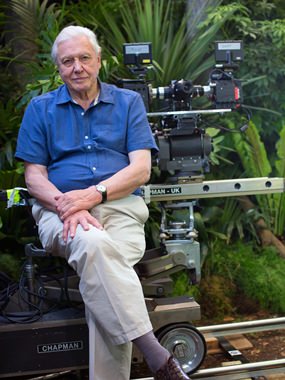

David Attenborough is shown during the filming of “Micro Monsters with David Attenborough,” a series about insects. (Colossus Productions/Smithsonian Channel via AP)

David Attenborough is shown during the filming of “Micro Monsters with David Attenborough,” a series about insects. (Colossus Productions/Smithsonian Channel via AP)

The sheer joy of continuing to work and learn keeps him “wanting to get up in the morning and have a go at it,” he said in an email. “It would be terrible if you knew it all, and nobody ever will.”

The British-born Attenborough, who plans to spend his birthday with family and friends, weighed in recently with The Associated Press on his six-decade legacy, the Earth’s future and the importance of getting to know bugs.

AP: What do people fail to understand about insects?

Attenborough: Knowledge is the great thing, superstition is the enemy. (It’s) superstition that all spiders bite, or are poisonous … so the more you know about these things, the better you are. If you know that a millipede is actually a vegetarian and it only has tiny little mouth parts and it can’t possibly bite you, then you are going to allow a millipede to crawl over your hand with no concern whatever. On the other hand, if you also know that a centipede which has fewer legs and moves rather faster and is actually inclined to be a hunter and it has a very poisonous bite, then you don’t handle a centipede.

AP: To what do you attribute your enduring curiosity and energy?

Attenborough: I’ve never met a child who’s not interested in natural history. Just the simplest thing, a 5-year-old turning over a stone and seeing a slug and (saying) ‘What a treasure!’ (and) ‘Well, how does it live, what are those things on the front?’ Kids love it! Kids understand the natural world is fascinating. So the question is (how does) anyone lose their interest in nature?

AP: What are the most critical problems facing the natural world today?

Attenborough: The rise in global temperature due to climate change is a very, very serious worry indeed. Children around the world today are going to inherit a very different world from the one I inherited — one which is much more crowded and one which has more severe problems than anybody could have supposed, certainly when I was a child. … I believe that if we find ways of generating and storing power from renewable resources, we will make the problem with oil and coal and other carbon fuels disappear because, economically, we will wish to use these other methods. And if we do that, a huge step will have been taken toward solving the problems of the Earth.

AP: As you turn 90, what do you count among your top achievements?

Attenborough: Television has become the visual medium which has really dealt with natural history in an unparalleled way, and the coverage of natural history is one of television’s feathers in its cap. … I went into television and particularly natural history because it was fun. … I reckon that I’m very fortunate in that I can look back and say, ‘Yes, it was worthwhile doing.’ We get letters from everywhere, from Russia, from China, from Hungary, from all kinds of people who say that they were moved and saw the value of natural history because of television.