Toronto (AP) – The name Deepwater Horizon is synonymous to most with environmental catastrophe and corporate negligence. For Mike Williams, who survived the April 2010 oil-rig explosion by plunging into the Gulf of Mexico from several stories up, it was about something else.

“My 11 brothers that got killed were immediately forgotten,” Williams said, speaking from his Sulphur Springs, Texas, home. “We understand the oil. It’s bad, yes. The birds are dying and the shrimp and the crabs and all that stuff. But those aren’t brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, sons, daughters. Shrimp can come back. People, you can’t bring those guys back.”

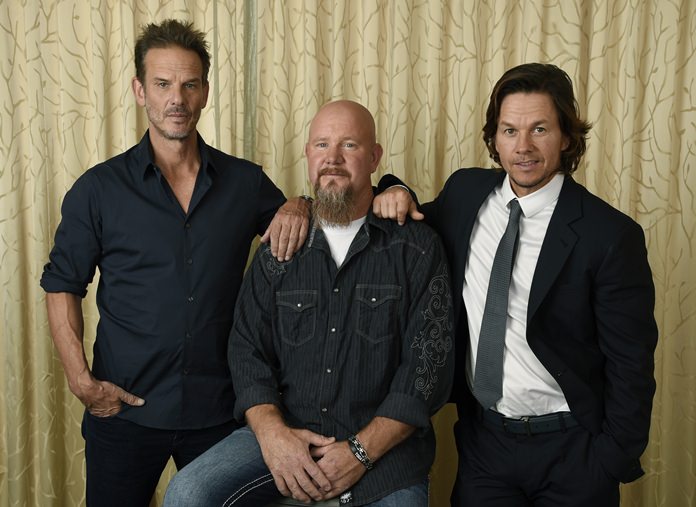

Peter Berg’s film “Deepwater Horizon” puts the spotlight of a big-budget disaster movie on the human toll of a real-life tragedy. Mark Wahlberg stars as Williams, a central figure in an earlier “60 Minutes” segment that focused on the Deepwater Horizon workers.

“There are probably several different ways you could tell this story or any story, but I liked this approach,” says Berg (“Friday Night Lights,” ‘’Battleship”). “I was very moved by the fact that 11 men lost their lives and I didn’t even know that before the ’60 Minutes’ piece.”

Made for over $100 million by Lionsgate, “Deepwater Horizon” gives the true story the kind of action-film treatment usually reserved for caped crusaders. A mock oil rig, 85 percent to scale, was built at an old Six Flags in Louisiana out of more than 3 million pounds of steel — one of the largest film sets ever erected. The film, based on a New York Times article that detailed the events surrounding the explosion, burrows into the details and politics of life on the rig leading up to the chaos-inducing blowout.

“It’s great that the studio would take the risk to make a movie that has no sequel potential,” says Wahlberg. “At a time when we get bombarded with superhero movies and other stuff that’s pretty mind-numbing, it’s nice to have a really smart, adult movie that has action.”

Though director J.C. Chandor originally helmed the project, Berg came aboard to lend the film a more movie star-based approach. “This film works on many levels and I think one of them is just a big-ass action film in the best possible way,” Berg says.

Berg’s last film, “Lone Survivor,” similarly sought to pay tribute to a hardened community (the US Navy SEALS) with kinetic verisimilitude. Many of the rig workers have small roles in the film or served as consultants, including Williams.

“Once the family members and loved ones heard that they were making a movie, they were all completely against it because they assumed that Hollywood was going to make a movie about the environmental disaster and their loved ones would be overlooked again,” says Wahlberg. “Once we were able to communicate to them what our intentions were, what the movie was going to be, then they all came onboard. We wanted to honor those people.”

Some may take issue that one of the largest environmental disasters in history has been reduced to a fiery action movie. “Deepwater Horizon” spends little time on the millions of barrels of oil that leaked into the Gulf of Mexico for 87 days after the explosion. Nor is there much scrutiny of BP, which was found primarily responsible for the spill by a federal judge in 2014. It has paid billions in cleanup costs, penalties and settlements.

“When it came down to who decided what, pointing figures, we didn’t want to do that,” says Wahlberg. “These guys do a very dangerous job.”

The primary figure of corporate greed is encapsulated by rig supervisor Donald Vidrine (played by John Malkovich with a devilish Cajun accent), who was found guilty of a misdemeanor pollution charge for a shoddy pressure test that precipitated the explosion. In the film, a money-centric, behind-schedule BP is seen as recklessly rushing past safety regulations.

Williams, an electrician who has given up the oil business to home-school his kids, says Berg told the story “right down the middle.” He hopes the film makes people more aware of the “dirty, dangerous, potentially toxic business” that fuels their cars.

“More than likely, the people who see this film are going to get in a car and drive to the theater,” he says. “Or even if they take public transportation, it still has to have some kind of fuel source. And even if it’s electric-powered, it still has to have grease, it still has to have tires — all, of course, petroleum products. When they make that connection, it will be a deeper connection to the men that died.”

“It’s the least I can do to speak for them,” says Williams, “because I’m still here and they’re not.”