At the recent Yehudi Menuhin International Competition for Young Violinists in Switzerland, I was delighted to see a large number of brilliant young musicians from China and other parts of South East Asia. There are several Chinese stars of classical music that are already household names in the West. But I bet that in the coming years, there will be many more. Just wait and see.

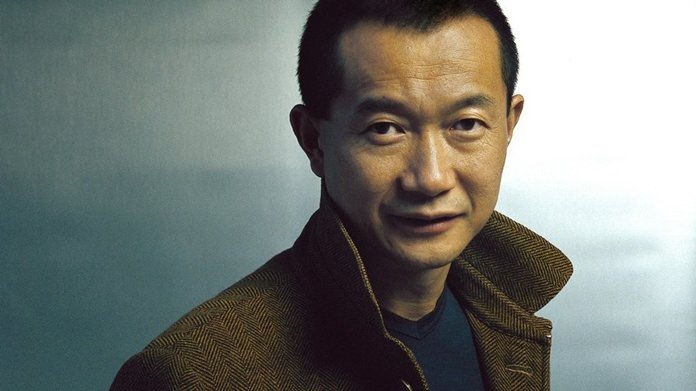

There are fewer Chinese composers who are well-known in Europe and America, though you may have come across Tan Dun. Even if the name seems unfamiliar, you may well have heard his music because this Oscar-winning composer wrote the film scores for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero.

In recent years China has embraced the Western classical tradition with unbounded enthusiasm. Today about thirty-six million Chinese children are studying piano, which must be heartening news for Chinese piano manufacturers of which there are over three hundred. Of course, it wasn’t always thus. The horrific catastrophe known as the Cultural Revolution which Mao Zedong launched in 1966 guaranteed that any form of western music wouldn’t stand a chance. The whole tragic saga continued for ten years until 1976, the year of Mao’s death. When violinist Isaac Stern arrived in China three years later for a series of concert appearances, there was evidently not one playable piano in Shanghai. All the instruments, including about five hundred pianos owned by the Shanghai Conservatory, had been destroyed.

Confucius believed that the study of music was “an indispensable way to train the mind.” By the 1980s, the Chinese Communist Party was beginning to re-embrace Confucian ideals and western classical music came back into favour. The success of today’s Chinese piano industry can be traced to the government’s decision to create nationalized piano factories in every major city in China. By the early 1990s, the government was deliberately encouraging the study of music through its education policy and pouring astronomical sums into magnificent new concert halls such as the Shanghai Opera House and the National Center for the Performing Arts in Beijing.

Tan Dun (b. 1957): Concerto for Orchestra (Marco Polo). New England Conservatory Philharmonia cond. Hugh Wolff (Duration: 35:00; Video: 1080p HD)

Tan Dun was born in China and moved to New York City in the 1980s to study music at Columbia. His music invariably fuses various musical styles. For example, at the start of this work which was premiered in 2012, he uses multiple rapids glissandi on the trombones and strings, as well as unusual pizzicato techniques for the string players.

The composer wrote: “This piece evolved from a concerto of mine commissioned by the Berlin Philharmonic and was written with my opera Marco Polo in mind. Marco Polo took three different journeys: a geographical, musical and spiritual journey.

“In the first movement Light of Timespace, Marco Polo is making his spiritual journey through time and space. The second movement Scent of Bazaar, opens to the scent of Eastern markets with the trumpets and brass representing the spicy flavours and powerful perfumes. With the third movement The Raga of Desert we hear Indian ragas where every note is alive and has an infinite number of expressions. For the final movement, Marco Polo makes his arrival in the Forbidden City and I was trying to imagine what kind of light, colour and sound he saw and heard there.”

If at first, you find the music something of a challenge, do keep listening. It is compelling, rhythmic and sometimes enigmatic music in which the composer creates fascinating musical soundscapes.

Chen Yi (b. 1954): Prospect Overture for Orchestra. China National Symphony Orchestra cond. Daniel Harding (Duration: 09:32; Video: 480p)

Chen Yi was born in Guangzhou, formerly known as Canton and she became the first woman to earn a Master of Arts degree in composition at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. At the age of seventeen, she was appointed Concertmaster of the Beijing Opera Company Orchestra but later moved to New York, receiving her Doctorate at Columbia. She has since become an award-winning composer and has written a great number of successful works in which she often blends Chinese and Western elements.

This work dates from 2009 and was commissioned by the China National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing. Her musical soundscapes are quite different from those of Tan Dun and there are many moments when distinctly tonal melodies emerge. According to the publisher, the work “is intended to reflect the eternal evolution and challenges of nature and its analogous relationship to the challenges of the human experience. The music presents the images of conflict, struggle, yearning, encouragement and triumph, to express the composer’s hope for the peace in the future of the world.” I have to admit that all that sounds to me ever-so-slightly pretentious. Probably better to ignore it and enjoy the invigorating music.

|

|

|