I am sure that you’ve heard of the Walt Disney film Fantasia. You may have seen it too, though you probably weren’t at the premiere unless you’ve been lying to me about your age. It was first shown nearly eighty years ago in 1940 and became a landmark in animated films. Over a thousand artists and technicians worked on the movie which featured over five hundred animated characters. The soundtrack was recorded using an elaborate set-up with multiple audio channels making Fantasia the first commercial film shown in stereo sound.

You may recall that all the music was arranged by Leopold Stokowski who also conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra on the sound-track. There’s an excellent print of the original 1940 version on YouTube though the stereo sound, which must have seemed wonderful at the time, now feels a little bit dated and it’s sometimes strangely unbalanced. Of course, the animations were created manually, for it was decades before computer-generated imagery was possible. It’s a remarkable movie for its time though to the modern viewer, parts of it look slightly kitsch and some of the animals are agonizingly cutesy.

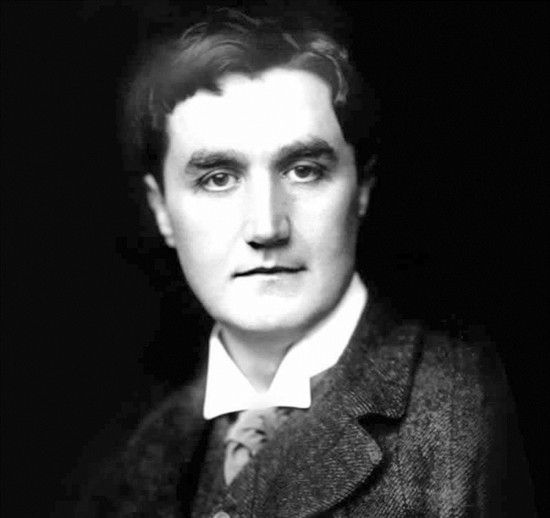

The name Fantasia was borrowed from the world of classical music where it appears in several variations such as fantasy, fancy and phantasy. The word first cropped up during the sixteenth century in various collections of keyboard music from Spain, Italy, Germany and France. The name itself implies music which is improvisatory in style and avoids a strict musical form. Several baroque and classical composers borrowed the term for works of an improvisatory nature and in the opening decades of the twentieth century, some British composers wrote fantasias, notably John Ireland, Herbert Howells and Benjamin Britten. But the two most well-known fantasias are those by the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. This is one of them.

I first heard this visionary work many years ago – early one morning in September, “just as the sun was rising” as the folk-song goes. The barely audible opening chords are played pianissimo and this one of the great magical moments in classical music. Vaughan Williams imbued his music with a kind of timeless quality and none more so that this much-loved Fantasia. It was composed in 1910 and takes its name from the English composer Thomas Tallis who was one of Europe’s leading sixteenth century writers of sacred choral music.

Scored for string orchestra, the composer divides the players into three groups. As well as the large main group, there’s a smaller one of nine players plus a string quartet. All this makes for an intensely rich and sonorous sound. At the first performance, Vaughan Williams obtained dramatic spatial effects by placing the three groups of strings some distance from each other.

Needless to say, the work sounds best in a church or cathedral, which is where the Tallis original would almost certainly have been heard and indeed where the first performance of the Fantasia was given. Vaughan Williams takes the relatively simple hymn-like Tallis melody and transforms it into something entirely new with a powerful depth of feeling, rich harmonies and a pervasive sense of Englishness.

In case you’re wondering, the “D number” refers to a numbered list of all Schubert’s compositions, compiled in 1951 by Otto Erich Deutsch. It’s usually known simply as the “Deutsch number”. The high Deutsch number of 934 indicates that it is a late work, the last in fact of Schubert’s compositions for violin and piano.

This challenging and difficult piece was premiered by the violinist Josef Slavík and the pianist Carl Maria von Bocklet at the Landhaussaal in Vienna. Slavík was one of the finest violinists of his day and was considered on a par with Paganini. The work was designed to display Slavik’s brilliant technique and even the piano part has been described by the Russian pianist Nikolai Lugansky as “the most difficult music ever written for the piano”.

It’s a long and complex work which proved too great an intellectual challenge for the aristocratic Viennese who turned up for the first performance in January 1828. As the performers valiantly soldiered on through the work, the hall gradually emptied and even the local music critic discreetly crept away. In the newspaper, he wrote rather dismissively, “The Fantasy occupied rather too much of the time a Viennese is prepared to devote to pleasures of the mind.” However, despite this inauspicious beginning, the Fantasia has become one of the standard works in the advanced violin repertoire.

|

|

|