Despite the ornithological theme, I have to admit that I’m not much good at recognising birds, even though my father could spot a great crested grebe at two hundred yards. Quite frankly I couldn’t recognize a great crested grebe if you hit me over the head with a stuffed one. I can manage owls, seagulls and swans but that’s about it. I suppose I might recognise a lark given a helpful clue, such as “This is a lark”.

Talking of larks, in Greek mythology the bird represented the break of day. Geoffrey Chaucer describes “the busy lark, messenger of day” in his famous work The Canterbury Tales. In one of his sonnets (the twenty-ninth, since you asked) Shakespeare wrote “the lark at break of day arising, from sullen earth sings hymns at heaven’s gate”.

I didn’t realise until yesterday that larks are sometimes kept as pets in China. In Beijing, larks are sometimes taught to mimic the calls of other songbirds or even animals. Apparently some Chinese people teach their larks thirteen different sounds in a certain order and – presumably after a bit of practice – the bird is expected to repeat the sounds from memory in the correct order. I would have thought that would be a challenge for many humans, let alone a Chinese lark.

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809): String Quartet, Op. 64 No. 5 “The Lark”. Attacca Quartet (First movement duration 06:31; Video 720p HD)

As you know, a string quartet consists of two violins, a viola and a cello. But it’s not just that. The four players have to work together for a considerable time to discover how they can function as a close-knit team, blend their separate sounds effectively, develop ensemble skills and make musical sense of what they’re playing. Sometimes it can take years.

The young Attacca Quartet is based in New York City and won first prize in the Seventh Osaka International Chamber Music Competition in 2011. The quartet was formed at the Julliard School in 2003 and has been praised by The Strad magazine for possessing “maturity beyond its members’ years”. The New York Times described their playing as “exuberant, funky and exactingly nuanced.”

The German poet and statesman Johann Wolfgang von Goethe described the string quartet as “a stimulating conversation between four intelligent people.” All of Haydn’s eighty-three string quartets provide a sophisticated musical experience in four movements, aptly described by composer Paul Epstein as “a story, a song, a dance and a party”. The notion of “a story” comes from the traditional structure of the first movement in which musical ideas and developed and juxtaposed.

In 1790 Haydn composed a set of six string quartets which were later published as his Opus 64 and The Lark is the fifth of the set. The nickname comes from the melody played by the first violin near the beginning. The second movement is beautifully lyrical and although it sounds relatively simple, to my mind it’s a fine example of art that conceals art. The third movement is traditionally a minuet and trio and here Haydn’s sense of humour shines through as well as his gift for making everything sound so interesting. The vivacious three-minute finale is perhaps responsible for the work’s popularity and in this performance the movement taken at a whirlwind tempo and the energy never lets up for a moment. Sparkling playing, too.

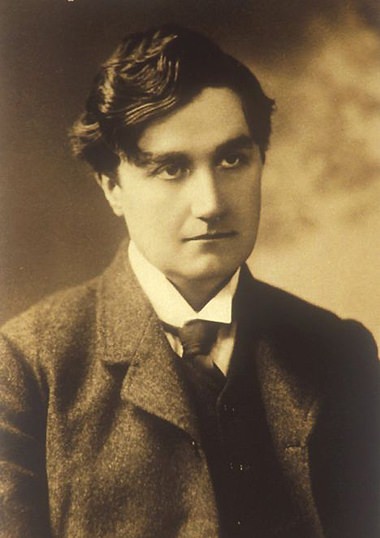

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): The Lark Ascending. Arabella Steinbacher (vln), North German Radio Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Andrew Manze (Duration: 18:11; Video: 480p)

George Meredith was an English novelist and poet, whose friends and acquaintances included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and J.M. Barrie, he of Peter Pan fame.

Meredith’s poem The Lark Ascending dates from 1881 when he once jokingly wrote that he had become afflicted by “the dreadful curse of verse”. Vaughan Williams was attracted to the poem and in 1914 wrote a piece of the same name for violin and piano which he orchestrated six years later. The title has a pleasing ring to it, which perhaps wouldn’t have been the case if Meredith had instead written a poem about the great tit or the little bustard.

This is lyrical evocative music in which the violin mimics the “silver chain of sound” that Meredith describes. There’s a wonderful and compelling sense of place too. It could only be England. Incidentally, when Vaughan Williams was making sketches for the piece in August 1914, he visited Margate for a short holiday on the same day that Britain entered the Great War. As bad luck would have it, a small boy observed the composer making notes and assumed he was writing some kind of secret code. The boy did his duty for King and Country and informed a police officer. Vaughan Williams was promptly arrested on the grounds of suspicious behaviour.

|

|

|