Does anyone suffer more in wartime than a child? All they know is at risk — parents, siblings, neighbors, homes, schools, even pets. All too soon they learn of hunger, death and inhumanity. Those who survive carry scars on their flesh and their minds — and they have stories to tell, if they can bear it.

“I want to forget,” says Liuba Alexandrovich, who was just 11 when she watched German soldiers shoot every third person in her tiny Soviet village, a reprisal for providing support to partisans opposing Hitler’s forces after their 1941 invasion. Later the soldiers gathered those whose children had joined the partisans and beheaded them. She says, “I want to forget it all.”

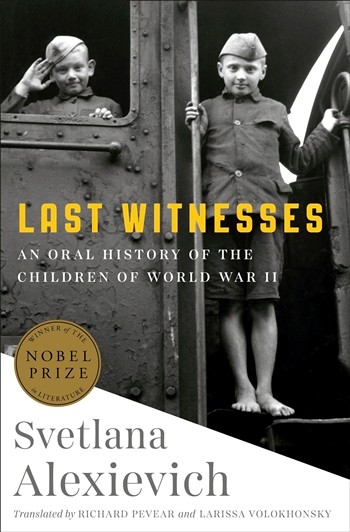

Belarusian writer and journalist Svetlana Alexievich believes such moments must be remembered and gives scores of Soviets an opportunity to tell their stories. Her engrossing book “Last Witnesses” first appeared in 1985, but its English translation is new, the third of Alexievich’s books to come from Random House since she won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2015. Readers of the late American writer Studs Terkel, the most celebrated oral historian in the U.S., will recognize the simple but powerful prose that comes from recording ordinary people’s memories.

More than 100 people speak in “Last Witnesses” and many recall similar horrors — planes and falling bombs interrupting playtime, soldiers burning villages and their inhabitants, people fleeing into forests, children burying parents in frigid ground, young ones eating grass or garbage or the family cat to survive.

There are hopeful stories, too, serving as streaks of light in the darkness. Some people recall acts of kindness, such as a single woman telling two young orphans wandering the countryside, “You’ll be my children now.” Or a farm family taking in a Jewish girl in spite of fear of discovery and certain death.

Except for occasional footnotes for context, Alexievich lets these children of war speak for themselves. One wonders why they would willingly revisit such times. Some, like Oleg Boldyreve, who was 10 when he went to work with his father in a bomb factory, weren’t sure they wanted to. “What’s better — to remember or to forget?” he asked. “Maybe it’s better to keep quiet? For many years I tried to forget.”

For Nadia Gorbacheva, who was 7 when the horrors began, the answer was simple: “I remember war in order to figure it out. Otherwise why do it?” (AP)

|

|

|