Can you remember the famous Merrie Melodies cartoons? They were made between 1931 and 1969 and three of them even won Academy Awards. The name sprung to mind as I recalled an occasion some years ago when I once became intensely irritated on hearing a well-meaning but ill-informed elementary music teacher talking to her class about “happy sounds” and “sad sounds”. She was trying to convince the children that the notes C and E played together sounded “happy” and that the notes C and E flat sounded “sad”. Of course, all this was complete and total nonsense and with as much tact and diplomacy as I could muster, I told her so.

It was unfortunate that the teacher was feeding her class the hopelessly naïve notion that music is either “happy” or “sad”. The other day I found an article in which someone had foolishly listed examples of “music that makes you happy”. A further Internet search revealed lists of music “which makes you sad.” It’s just far too superficial. Perhaps it’s too subjective to warrant such a list because an individual’s reaction to music is informed by their frames of reference, not to mention cultural background or personal taste and experience. Anyway, the important thing is that there are countless shades of meaning and emotion between and outside the simplistic notions of “happy” and sad”.

Some music can be so full of radiant joy and elation that it makes your spirits soar and you find yourself weeping. Now why is that, I wonder? Well, my knowledge of psychology is such that I’d prefer to leave that for you to ponder. You may recall that Hans Christian Andersen once wrote, “Where words fail, music speaks”.

Even so, I can think of many pieces that uplift the spirits and brighten the day. Perhaps they even evoke a sense of merriment – for at least part of the time. But with the possible exception of Swiss accordion players, most musicians know that unrelenting jollity can become wearisome. In Gustav Holst’s The Planets the fourth movement is entitled Jupiter the Bringer of Jollity but the jovial mood soon gives way to one of his noblest melodies. Dvorak’s effervescent and sprightly Carnival Overture includes a beautiful middle section of almost heart-breaking nostalgia. And talking of overtures, here are two that might lift your spirits, assuming of course that you feel the need to have them lifted.

In case you’d forgotten (or possibly never knew) Galicia is an autonomous community in Spain which lies in the far north-west corner of the country just north of Portugal. Go any further north-west and you’d be sloshing about in the Atlantic. Their local orchestra gives a superb performance of this Bernstein classic and I enjoyed it more than that the performance by Bernstein himself with the London Symphony.

Bernstein’s operetta Candide was first performed in 1956 and based on the novella of the same name written almost exactly two hundred years earlier by the French writer, historian and philosopher François-Marie Arouet, better known by his pseudonym Voltaire.

The overture is a lively and engaging work with a catchy opening theme which gives way to a passionate melody (01:24) that recurs triumphantly later in the work. This theme has a wonderfully fluid quality produced by using alternate bars of two and three beats. The overture combines energy, delight, passion and vulgarity and the exciting Rossini-style crescendo (04:57) drives this heart-warming work to a satisfying conclusion.

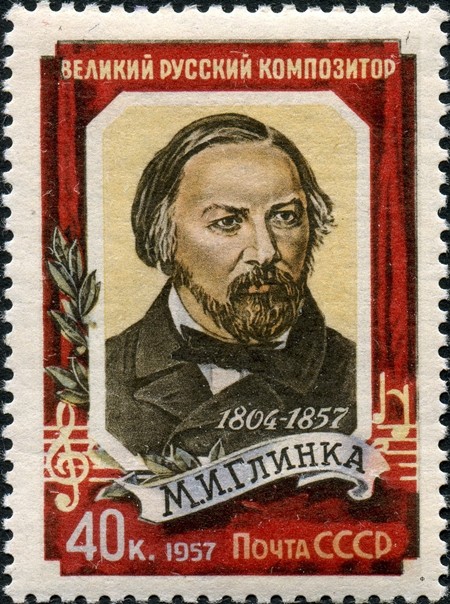

This is a sizzling overture, which I first came across at the age of fourteen. It’s remarkable that the music sounds so modern for something written in 1840. The overture is taken from Glinka’s opera of the same name which was based on an epic fairy-tale poem by Alexander Pushkin. In case you’re wondering, Ludmilla is the daughter of a prince and the damsel in distress who is rescued from the clutches of a wicked wizard by the brave knight Ruslan. Of course, there’s more to it, but that’s the gist of the plot.

Glinka is considered the father of Russian classical music and although he was a tremendously prolific composer, today he’s known in the West for only a handful of works. He’s highly regarded in Russia where three different music conservatories are named after him.

Conductor Valery Gergiev takes the overture at a hair-raising speed, revealing the competence of this superb Russian orchestra. A lesser band would probably disintegrate at this frenetic tempo. As he so often does, Gergiev appears to be conducting with the aid of a toothpick. You’d have thought with the fees he demands, he could afford to buy a decent baton.

|

|

|