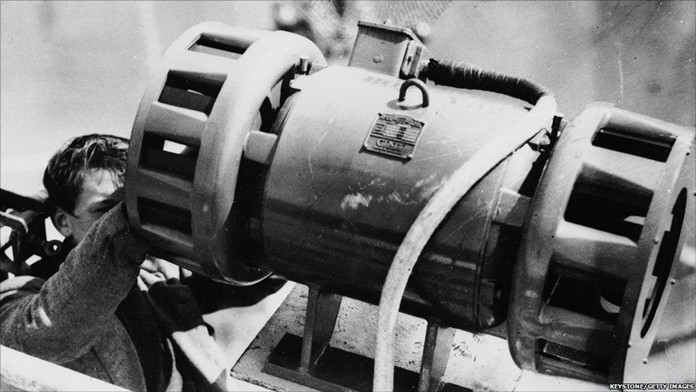

A long time ago, when I was two or three years old, we lived in an English village not far from the town of Crewe. Every few days, I remember hearing dull, booming thuds which my mother assured me were caused by trucks bumping along the road outside. This seemed a bit unlikely as we rarely saw any trucks in the village. The noise was in fact coming from German bombs exploding in the distance. Crewe was known for its large railway junction and its enormous railway engineering facility for manufacturing and overhauling locomotives. During World War II, military tanks were also built there, so the town naturally became a favourite target for the German Luftwaffe. The air raids were preceded and followed by the distinctive wailing sound of air-raid sirens which were installed in almost every town and village in the country. Sadly, for many people the air-raid siren was one of the last sounds they heard.

At that tender age, I used to tinkle around on my grandmother’s piano. My earliest musical memory was the discovery that the notes B flat and D flat played simultaneously sounded almost exactly the same pitches as the wailing air-raid sirens. I was tremendously excited about this revelation though no one else shared my enthusiasm. Perhaps they were more concerned about the bombs. Years later, I discovered that the notes B flat and D flat create a musical interval called a minor third. You might be wondering what it sounds like, especially if you can’t tell a B flat from a wombat’s armpit. Think of the song Greensleeves and sing the first two notes. Or sing the first two notes of the Beatles song Hey Jude. Then imagine those two notes sounding together. That’s a minor third, assuming that you’re singing in tune.

The distinctive sound of the minor third helps to create the character of music in minor keys. Some people describe the minor key as dark-sounding, soulful or heart-rending. Many folk songs in minor keys tend to stay in the minor throughout, but if a symphony is described as being in a minor key, you can be sure that it will drift into a bright and sunny major key sooner or later. Strangely enough, during the late eighteenth century, composers tended to avoid minor keys. Only two of Mozart’s forty-one symphonies are in a minor key and Haydn, who wrote over a hundred symphonies, chose minor keys for only seven. Only two of Beethoven’s nine symphonies are in a minor key. This might be a reflection of contemporary Viennese public taste because as the Romantic Movement surged across Europe during the 19th century, more symphonies appeared in minor keys. But let’s explore two less well-known symphonies, both in minor keys and both equally rewarding.

Considered the grandfather of American music, Charles Ives was born in Danbury, Connecticut. This attractive work is the first of four symphonies and was composed between 1898 and 1902. It’s written in a late romantic European style and the second movement is exceptionally beautiful and moving, evoking an atmosphere similar to the slow movement of Dvorak’s New World Symphony. The scherzo is delightful with a tuneful dance-like trio section while the last movement is a real tour-de-force with thrilling brass writing.

Later in life, Charles Ives was among the first American composers to engage in daring musical experiments which included elements of chance. He also experimented with tone clusters and “polytonality” a word which means music played in several different keys at the same time. However, all this proved too much of a challenge for most audiences and his music was generally ignored, largely because of the relentless dissonance. It was Ives who famously said, “Stand up and take your dissonance like a man.”

Scriabin’s Third Symphony is subtitled The Divine Poem and was written between 1902 and 1904. The work marked a significant step towards Scriabin’s personal musical language and has a visionary quality which was only hinted at in his earlier works.

Scriabin liked a massive orchestral sound and at times, he turns the orchestra into an ensemble of soloists; each contributing points of detail to a complex web of sound texture. It’s been suggested that his emotionally-charged, highly personal music reflects the notions of nineteenth century existentialism and the mysticism of the famous, if slightly dotty Madame Blavatsky of the controversial Theosophical Society. Anyway, if you enjoy romantic, orchestral wall-to-wall sound, Scriabin’s Third Symphony will probably be right up your soi.

|

|

|