Chatting with a friend over coffee recently, we were reminding ourselves about famous movies that used classical music for their sound tracks. Driving back home, I began to realize that a classical music soundtrack is not such a novel idea as I first imagined. The concept goes back to the earliest days of cinema. I read somewhere that music was originally played during silent films not for any artistic purpose, but was merely intended as a distraction from the continuous clatter of the projector. It was usually provided by a pianist and many helpful books were published to provide accompanists with suitable musical examples for various scenes. It eventually became common practice for film distributors to provide musical cue sheets with each print of the film. I would guess that because many cinema pianists were classically trained, they would also draw on their knowledge of the classical repertoire to supplement their partly improvised performances.

Please Support Pattaya Mail

The first days of January 1915 saw the premier of the movie Birth of a Nation, hailed for its dramatic and visual innovations. With a running time three hours it was longest film ever made up to that point and its use of music was also something of a revolution. But the film itself was silent because sound-on-film technology was not developed until the mid 1920s. The composer and conductor Joseph Carl Breil assembled a three-hour score for Birth of a Nation intended to be played by an orchestra during the screening. He used adaptations of classical works together with well-known melodies and newly composed music. During the early years of sound film, classical music was used freely, especially music from the nineteenth century.

But once the ability to synchronize music and sound became possible, the role of background music started to become an integral part of the movie and part of the story-telling process. Thus began the role of the film music composer. Some of Hollywood’s most influential film composers such as Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold came from Austria or other parts of Eastern Europe and their musical roots were deeply embedded in European romantic tradition. This is indeed where the characteristic Hollywood Sound came from, with its soaring melodies, rich orchestral textures and sumptuous harmonies.

Even so, some film directors were drawn to classical music to underscore their films. I suppose one obvious reason might have been that composers do not demand fees or royalties when they have been dead for two hundred years. But more importantly, classical music can add a sense if historical framework, it can add a depth and breadth that is otherwise rarely achieved. Just think back for a moment to some of the most compelling cinematic moments: the opening scene of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey enriched by the powerful music of Richard Strauss; the melancholy sequences in Visconti’s Death in Venice which used music by Mahler and the brilliant use of Wagner’s music in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now.

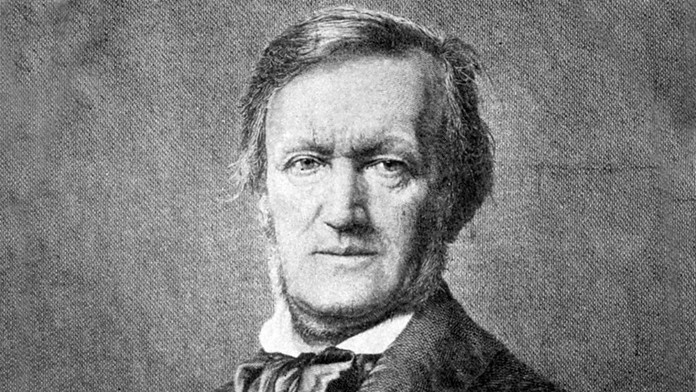

It’s difficult to hear this piece without mental images of helicopters surging towards the coast of Vietnam; such was the impact of the music in Coppola’s movie, in which at first the music is barely audible under the ominous drone of the helicopters then comes surging forward. The music dates from the 1850s and is part of the opera Die Walküre (The Valkyries) which is the second opera in the four that make up Wagner’s great opera cycle, Der Ring des Niblungen. And case you’re wondering, a Valkyrie is a female god-like being from Norse mythology who chooses those who will die in a battle and those who will live. The music gives the spotlight to the brass instruments but in the original operatic version we hear the battle cries of the Valkyries above the orchestra. The orchestral version, without the shrieking Valkyries has become one of Wagner’s most well-known works. Incidentally, I discovered this morning that this work was also used in Joseph Carl Breil’s score for Birth of a Nation.

A few nights ago, I watched a cleaned-up print of David Lean’s 1945 classic movie, Brief Encounter. After all those years it is still a wonderful experience and in many ways a remarkable movie. Throughout the film Lean draws on excerpts from Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto, one of the great piano works of the twentieth century, though its heart is firmly in the nineteenth. As a teenager, I adored this work and eventually saved up enough money to buy the Deutsche Grammophon recording of the brilliant Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter playing it. The dreamy and lyrical slow movement used to reduce me to a helpless sniffling wreck. Sometimes, it still does.

|

|

|