New York (AP) – In the latest chapter of a scandal that’s jolted New York’s art world, a federal jury is hearing about a Chinese immigrant who forged fakes of modern masters such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko in his garage, a once-reputable Manhattan gallery that sold them and the wealthy buyers who paid millions for the knockoffs.

“I got a fake painting for $8.3 million and they don’t want to give my money back to me,” Domenico De Sole, the chairman of the board at Sotheby’s auction house and a former Gucci CEO, groused from the witness stand at the high-stakes civil trial that continued this week.

His wife Eleanore — testifying with the faux color-block Rothko called “Untitled, 1956” unceremoniously propped up on an easel next to the witness stand — told jurors she “went into a shaking frenzy” when she first learned of suspicions about it.

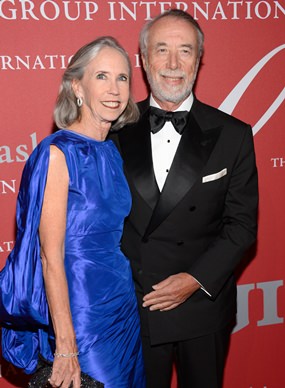

Domenico De Sole and his wife Eleanore are shown in this Oct. 23, 2014 file photo. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP)

Domenico De Sole and his wife Eleanore are shown in this Oct. 23, 2014 file photo. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP)

The couple sued the Knoedler & Company gallery and its former director, Ann Freedman, in 2013 after federal prosecutors brought a separate criminal case against Long Island dealer Glafira Rosales, who admitted in a guilty plea that she sold or consigned 40 fakes to the gallery before it closed in 2011 after more than a century. The De Soles are seeking $25 million in damages, claiming Freedman should have known the painting was a forgery.

The defense has portrayed Freedman, who wasn’t charged in the criminal fraud, as a victim as well. It also contends the evidence will show that the forgeries were so good — and such a surprise — even respected art experts lost their bearings.

“This is the art world equivalent of finding dinosaur bones,” Freedman’s attorney, Luke Nikas, said in opening statements. “This was an important discovery. Ann believed in it and the art world believed in it.”

The fraud dates to the 1990s, when Rosales, her partner and her boyfriend discovered future forger Pei-Shen Qian painting portraits on the streets of lower Manhattan. The dealer learned the artist had trained at the same art school attended by Rothko and other famous abstract expressionists — and had a knack for mimicking their style.

Qian, who was charged criminally but has fled to China, began painting fakes of Rothkos and others in his garage at his Queens home in exchange for a few hundred dollars up to $9,000. The dealer then began taking them to the Knoedler gallery, where she told Freedman they were undiscovered works supplied by the anonymous son of a deceased Swiss collector.

After obtaining “Untitled, 1956” for $950,000, Freedman sold the painting to the De Soles for more than $8 million in 2004. The couple hung it on the wall at their Hilton Head, South Carolina, home, believing they were the owners of a museum-worthy Rothko.

“I thought it was beautiful,” Domenico De Sole testified.

Pressed on cross-examination on why he hadn’t done more to authenticate the painting, De Sole shot back, “I had complete trust in (Freedman) and Knoedler. It never crossed my mind that these guys were in the business of selling fake art. Is that clear?”

The defense insists Freedman was so completely conned that she paid nearly $300,000 for a phony Pollock drip painting in 2000 and displayed it in her apartment for a decade, even though the artist’s signature was misspelled “Pollok.” It also claims art experts who saw the Rothko were believers as well, and have asked the jury to be skeptical of testimony that they never actually authenticated the work.

“The experts were fooled,” defense attorney Nikas said. “And now they feel like fools.”

De Sole lawyer Emily Reisbaum told jurors that, at minimum, Freedman was at fault for ignoring obvious red flags such as the proliferation of pieces from the mystery collection over a 15-year period and Rosales’ willingness to sell them to the gallery at prices far below market value.

“Your common sense will tell you,” Reisbaum said. “Such a treasure trove of never-before-seen masterpieces by America’s most famous artists was too good to be true.”