Back in the Old Country on the bleak island where we lived, my parents would often take me for a jaunt in our ageing car, pottering around the familiar country lanes with their high hedgerows and grey stone walls. My father enjoyed taking a road less travelled, with the words, “I wonder where this road leads?” And with that, we’d turn into some country lane eager with anticipation. Sometimes it would lead to a farmstead and we’d end up in a muddy yard surrounded by mystified cows and pigs. Other times we’d find a tiny pebbled beach, a small forgotten forest or come over the brow of a hill to a sudden vista that stretched to the far horizon.

The musical world is full of byways too, along which comparatively few people have ventured. As a teenager, I loved to travel those roads and I still do. For us kids who lived out in the sticks yet wanted to hear classical music, the BBC’s so-called Third Programme was a cultural lifeline. It went on the air in 1946 and for decades played a leading role in disseminating classical music to the farthest flung corners of Britain.

Coming home one day after a jaunt in the car with my parents, I switched on the radio in the music room. We didn’t have a radio in the car. (“Too distracting,” my father used to say.) The radio was an enormous polished wooden thing and after the valves had warmed up, the sound of cello music emerged from the loudspeakers. It was music I’d never heard before, with oddly angular melodies and captivating turns of harmony. I didn’t realize at the time, at least not until the announcement at the end of the piece, but I was listening to Martinù’s Third Cello Sonata, which had been written only a few years earlier. For years afterwards, I bought every recording of Martinù’s music that I could lay hands on, most of which appeared on the Czech Supraphon label.

Bohuslav Martinu was an incredibly prolific composer and churned out six symphonies, fifteen operas, fourteen ballet scores and countless other orchestral, chamber, vocal and instrumental works. In his younger day he was a violinist in the Czech Philharmonic and taught music in his home town. As a composer he experimented with different musical styles yet from his earliest work a highly personal sound began to emerge.

Martinu (MAR-tih-noo) had a rather curious childhood. He was born in a church tower in a small town in Bohemia. His father held a part-time job in the church and as a reward was allowed to live in some rooms up in the church tower. The young Bohuslav was a sickly child and frequently had to be carried up the 143 steps to his room on the back of his father or his elder sister. In adult life, he was quiet, introverted, and socially uncomfortable. Close friends found him to be a kind, gentle and somewhat self-effacing individual. Research during the last decade has revealed evidence that Martinu was autistic and probably had Asperger syndrome.

If you’re unfamiliar with his music, this 1951 chamber work would make an excellent introduction. It was written when the composer was settled in New York and a splendid example of how Martinu was able to blend traditional Czech idioms with more modern sounds. His characteristic personal sound is instantly recognizable in the opening bars.

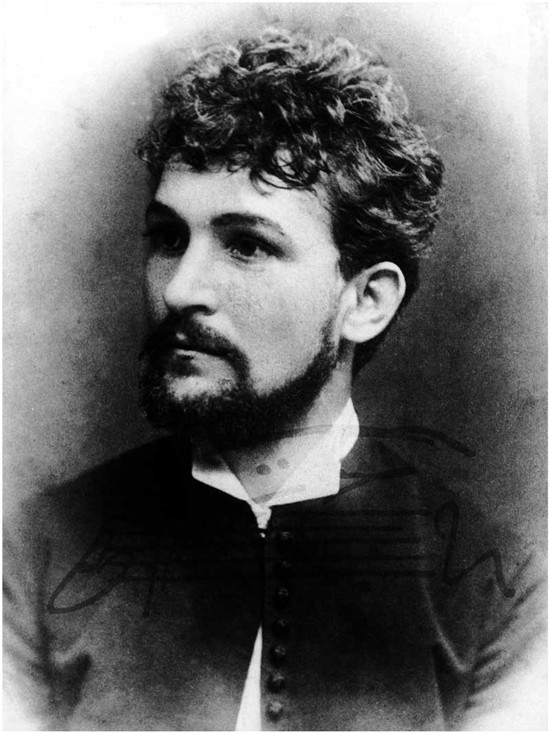

In case you’re wondering, A Far Cry is the somewhat unusual name of a string orchestra based in Boston. It is small enough to perform without the need of a conductor. The members of the orchestra tend to play standing up, which gives much more freedom of movement. They give a splendid performance of this little-known work by Janácek (yah-NAH-check) who today is considered one of the most important of all Czech composers. The suite is an early work written in 1877 when Janácek was aged twenty-three and a penniless music student in Prague. At about the same time, he became the conductor of the Brno Music Society which at least must have brought him a bit of much-needed extra income.

This delightful six-movement work seems to speak of another age. From the opening notes you can hear echoes of the yearning folk songs and lively country dances of Janácek’s native Bohemia. It’s often said that his musical style absorbed elements of Moravian and Slovak folk music and for many years Janácek took and active interest in his country’s folklore. Oddly enough, there are moments when the music sounds almost English. Despite being a student work, it’s compelling, charming music yet gives few hints of Janácek’s tormented and powerful musical style which was to emerge in years to come.

|

|

|