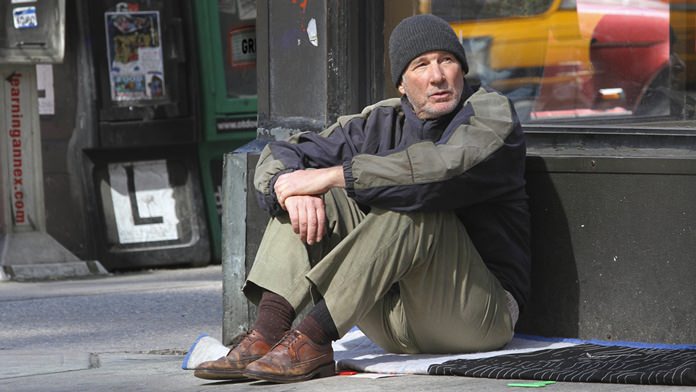

New York (AP) – The last time Richard Gere walked into this bar, he did it as a homeless man.

Gere plays one in “Time Out of Mind,” a movie that he shot almost entirely on the streets of Manhattan – in East Village back allies, among the trash cans outside Grand Central Station and inside the Houston Street bar he’s returned to in order to reflect on an unusually spare and neo-realistic movie, one Gere has wanted to make for more than a decade.

“I really believe this was one of the things I was meant to do,” says Gere, sitting in a booth in the back.

Inspired by the photography of Saul Leiter, director Oren Moverman (“The Messenger, “Rampart”) frequently shot Gere from far away, hiding the camera from view to capture an unwitting city moving around one of the more famous faces on the planet.

It was an audacious approach, one that, if successful, would only further prove part of the movie’s point: Most of us are oblivious to those suffering around us. Gere (also a producer) and Moverman nervously gave it a test run on the first day of shooting in the East Village’s Astor Place, where the man forever linked to “Pretty Woman” begged for change with a coffee cup.

“As someone who would probably never stand on a street corner that long, it was an anxiety-ridden moment,” Gere recalls. “None of us really knew what was going to happen. We thought maybe we would get five minutes before crowds started to screw up the shot, that I would be recognized and it would be over. A couple minutes into the shot, we realized no one was paying attention.”

They went on shooting unnoticed for 40 minutes, and the same lack of recognition continued throughout the production.

“They could have seen Richard Gere if they looked into his eyes,” says Moverman. “Here we are putting make-believe in the middle of reality, and reality is saying, `No, that’s reality. That’s not make-believe.’ It doesn’t matter who it is.”

In “Time Out of Mind” Gere plays a vagrant named George Hammond whose unfortunate fate is teased out slowly and without sentiment. His backstory comes through only in Moverman’s patient observation of his movements around New York.

The movie doesn’t just capture George’s story, though. It’s a close-up of the soul-crushing experience of homelessness: the omnipresent assault of noise, the indignities of shelters, the sanity-shattering invisibility. But it’s also a wider view of urban life where the normal occupations of people are going on all around him.

“Are we all in this together or not, is basically the question,” says Gere. “Somehow, we’ve gotten habituated to this idea that we’re in our separate capsules. It’s not true.”

Gere, a longtime New Yorker, first got a pass to homeless shelters 12 years ago. He’s worked with the Coalition for Homeless for years and refers to his “homeless friends” he’s gotten to know while researching the film. He took a lot of inspiration from the Cadillac Man memoir of homelessness, “Land of the Lost Souls: My Life on the Streets.”

Getting to actually experience the feeling of begging, if only for hours at a time, Gere says, was more like being a black hole than being invisible. He could feel people avoiding him, going through an “interior opera” of guilt that he notes, ultimately “has very little to do with the reality of that guy on the street corner.”

It gave him a taste of “how quickly we deteriorate mentally.”

“He was shaken by the experience because this is a man who for 40 years is used to being looked at and admired by most and paid attention to and showered with attention and love,” says Moverman. “Here he was dealing with immediate rejection, with a need to get away from him, a toxicity he was bringing to the street corner.”

In between takes on the very low-budget film, Gere would wait in a rental car. The one luxury he allowed himself was a tea kettle he could plug into the car. For the longtime Buddhist, there were “monk-like” lessons of humility in playing George.

None of it, perhaps, is how many would expect the 66-year-old Gere, most famous for less extreme Hollywood productions, to be spending his time. But his filmography has always been dotted with more daring than he’s often given credit for, from 1978’s “Days of Heaven” to 2007’s “I’m Not There” to 2012’s “Arbitrage.”

“Time Out of Mind,” which he hopes leads to more collaborations with Moverman, is part of a recent string of films for the still ambitious Gere.

“I’m not going to waste any time,” he says. “I’m still enjoying this.”