The first time I visited New England it was back in the seventies and I’d decided to rent a car in Boston. I had specifically requested a small one, though I can’t remember why. The rental place was in a cavernous gloomy basement off Copley Square. Having signed a couple of forms, the office person gestured vaguely in the direction of a fleet of cars lined up in rows. I searched in vain for a small one. An assistant finally emerged from the office and led me to an enormous dark green thing which turned out to be a Mercury Cougar. Eventually, I hesitatingly drove out into the streets of Boston, but after years of driving a tiny car in Britain, I felt as though I was navigating an aircraft carrier.

I eventually fell in love with the green car; the light-as-a-feather power steering, the smooth automatic transmission and a suspension system that made it feel you were riding on a blancmange. The real thrill came when I drove out on the interstate across Massachusetts. I switched on the radio, poked a tuning button and out came the sounds of bluegrass music. This normally doesn’t do much for me but on that occasion, sweeping along the Massachusetts Turnpike at a stately 55 mph, the country music was strangely appropriate. It felt just right.

At the time, it hadn’t dawned on me that New England was the home of American “classical” music. William Billings was regarded as the first American choral composer. He lived in Boston and was described as “a singular man of moderate size, short of one leg, with one eye…and with an uncommon negligence of person.” One of his less scruffy contemporaries rejoiced in the name of Supply Belcher and was one of a group of mostly self-taught composers who wrote music for amateur local choirs.

The first American composer to write for symphony orchestra was the mildly eccentric Anthony Philip Heinrich. He gave his compositions rambling titles such as The Dawning of Music in Kentucky, or the Pleasures of Harmony in the Solitudes of Nature. One critic referred to him as “the Beethoven of America.” As the nineteenth century marched onward, a new breed of composers began to emerge who had studied in Europe but returned home to compose, perform and acquire students. Among them were George Whitefield Chadwick, Edward MacDowell, and Horatio Parker.

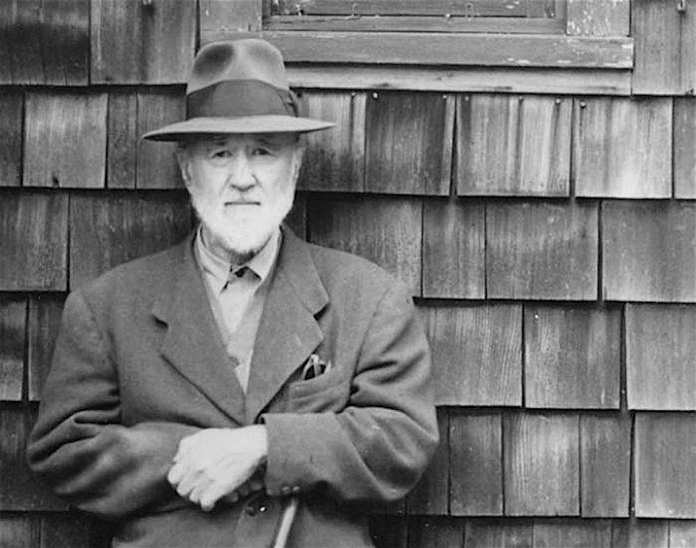

Considered the grandfather of American music, Charles Ives was another New Englander born in Danbury, Connecticut. As a child he played drums in his father’s marching band and must have tramped down many a road in his home town.

In 1894 he entered Yale University to study with Horatio Parker. He became a leading student and later in life was among the first composers to engage in daring musical experiments which included polytonality, polyrhythm, tone clusters and elements of chance. All this proved too much of a challenge for most people and his music was generally ignored, partly because of the relentless dissonance. It was Ives who famously said, “Stand up and take your dissonance like a man.”

This attractive symphony is the first of four and was composed between 1898 and 1902. If you’ve heard his later works this might come as a surprise because it’s written in a late romantic European style. The second movement is exceptionally beautiful and moving, evoking an atmosphere similar to the slow movement of the New World Symphony. The scherzo is delightful with a tuneful dance-like trio section, while the last movement is a real tour-de-force with thrilling brass writing, bringing the work to a joyful and triumphant conclusion.

Adams was also born in New England. In Worcester, Massachusetts to be precise. According to the composer, the piece was inspired by an early morning ride in a sports car that he took with his brother-in-law. One can only assume that they ignored the speed limit. This is one of his most approachable works and dates from 1986. Adams said that the piece has the “idea of excitement and thrill and just on the edge of anxiety or terror”.

This exhilarating piece is an iconic example of his so-called post-minimal style, which uses the characteristic techniques of repetition, a steady beat, the repetition of short musical ideas and perhaps most importantly, a tonality that relies on consonant harmony. Short Ride in a Fast Machine is a joyfully exuberant piece and brilliantly scored for a large orchestra, conducted in this video by Marin Alsop, one of today’s most successful female conductors.

|

|

|