If you’re into cars, the title will probably bring to mind the Jaguar “S” type that first appeared amid a great deal of hype in 1998. It was met with a mixed response. Journalist Richard Hammond cruelly remarked that it looked like “something washed up on a beach” while another critic, presumably referring to the car’s gawping radiator grille, said it resembled “a dead cod”. Anyway, I am digressing. This column is not about Jaguar cars, but about composers whose names begin with an “S”. And I am sorry if this comes as a disappointment, but life is full of disappointments so you may as well get used to them.

If you’ve ever assembled a collection of classical recordings and felt compelled to store them in alphabetical order, you’ll know that a disproportionate amount of space for the composers whose surname begins with either a “B” or an “S”. The German Baroque was partly dominated by The Three Esses: Heinrich Schütz, Johann Hermann Schein and Samuel Scheidt. And yes, in case you were wondering, his name really does rhyme with “height”. Later years brought us Schubert, Schumann, Smetana and the prolific Strauss family. The 20th century saw the appearance of dozens of Esses, notably Stanford, Sibelius, Scriabin, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Schedrin, Schoenberg, Schnittke and Skalkottas. There are hundreds more of course, many of whom languish in utter obscurity and likely to do so for a considerable time.

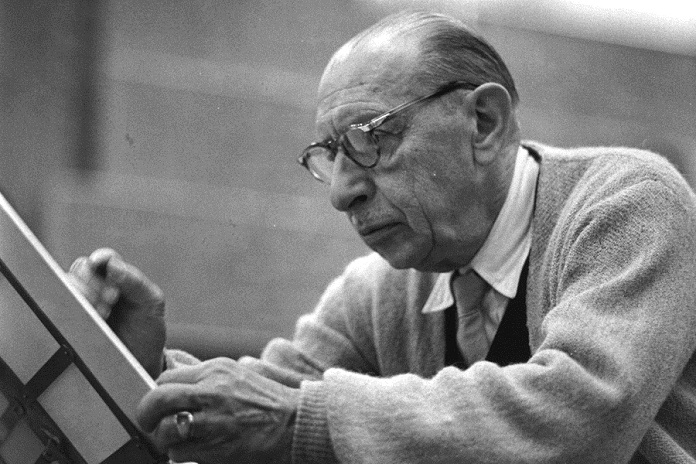

I’ve always had an admiration for the music of Stravinsky. As a teenager, I once heard a radio performance of The Rite of Spring, a work which famously caused a near-riot at its first performance in 1913. When I first heard it, the music seemed the best thing since sliced bread. And if these things interest you, sliced bread first appeared in 1928 by which time Stravinsky had achieved world fame. I bought the record at the earliest opportunity though some family members were not impressed. “Not many tunes,” sniffed a maiden aunt. She was wrong, because the work is absolutely loaded with tunes. They are just not the type of tunes you hear errand boys whistling. And what happened to them, I wonder? I haven’t seen an errand boy for decades.

It is probably safe to say that I am the only person in Thailand who has spoken to Stravinsky. It was in the mid-1960s. He was a super-star and I was an undistinguished music student but wanted to interview him so I brazenly phoned London’s Savoy Hotel where he was staying. To my amazement the operator put me through. It would have been pleasing to tell you that Stravinsky invited me over for tea and cakes. But he didn’t. The Great Man was not very pleased. Not very pleased at all. To be fair, he had a bad cold and was in a tetchy mood. In his squeaky gnome-like voice and almost impenetrable Russian accent he told me, in no uncertain manner, to sod off.

For decades The Rite was considered virtually impossible to play by all but the best orchestras. Hearing these fine professionals perform the work is thrilling and this is one of the best performances of the work that you’re likely to encounter. The haunting opening melody is a bassoon solo which begins on a tricky high note that only advanced players would attempt. Stravinsky piles musical fragments on top of each other in different keys and rhythms, creating a wonderful chaotic-sounding tapestry of sound. Notice the famous pounding rhythm at 04:05 which has been shamelessly copied by film music composers ever since. This is a powerful, crisp performance which Sir Simon takes at a lively pace and conducts the incredibly complex score from memory.

Here’s another “S” whose music doesn’t get played too often these days, especially outside his home country of Greece. The work consists of thirty-six Greek dances and this performance features five of them. You can’t miss the distinctive Eastern European flavours that pervade this lively music. The first dance Epirotikos has Hungarian overtones and shades of Bartók with percussive, insistent rhythms and brilliant string writing. The remaining dances are characterized by incisive spiky rhythms, contrasted with quieter reflective passages. The fourth dance Arkadikos is romantic in outlook with lovely folk-like melodies. The final dance really whirls along and lifts the spirits. And talking of which, a glass or two of Metaxa would make a pleasing accompaniment to this lovely music. Oh, and I am sorry if you still feel disappointed about the Jaguar. I really am.

|

|

|