When I was a teenager back in The Old Country I went through a phase of wanting to play the trombone. Perhaps you did too. I eventually borrowed a trombone for the weekend and taught myself to play a couple of simple tunes. But the affair was short-lived. The trombone and I didn’t seem to get on terribly well so we went our separate ways. I never tried to play a trombone again.

At first glance, the trombone looks deceptively simple. It isn’t of course. The basic model is devoid of complex mechanism and daunting-looking valves. A student trombone consists of a mouthpiece, a slide mechanism and a cylindrical tube which flares into a bell at the end. Like all brass instruments the tones are formed by vibration of the player’s lips and the different notes are produced by placing the slide in various precise positions. The characteristic sliding sound known technically as a glissando which is frequently heard in traditional jazz, is rarely used outside the genre. More expensive trombones have additional tubing up at the top end of the instrument. If you want to know why, ask a professional trombone player who will keep you entertained for hours with the explanation.

The word “trombone” comes from the Italian tromba (trumpet) to which the suffix one (big) has been added thus giving us a word which means “big trumpet”. This is rather a misnomer because the trombone looks nothing like a trumpet. The first trombones appeared during the late fifteenth century and were known as sackbuts. They were in use all over Europe until the eighteenth century.

The instrument was slow to enter the developing orchestra. Its first significant symphonic appearance was not until 1808 when Beethoven used trombones in his Fifth Symphony. Within ten years the instrument had become a regular member of the orchestra. The “standard” trombone is known as the tenor trombone but bass trombones often appear in most orchestras and the small alto trombone is sometimes seen in performances of baroque music. There’s also a valve trombone, popular among some jazz musicians but otherwise seldom encountered.

Many later nineteenth century composers were drawn to the majestic sound of three trombones playing together. With the addition of a tuba, the huge sound was irresistible. But the trombone has a quieter character too. In competent hands, the instrument is capable of a wide range of expression. Just listen to the slow movement of this concerto, for example.

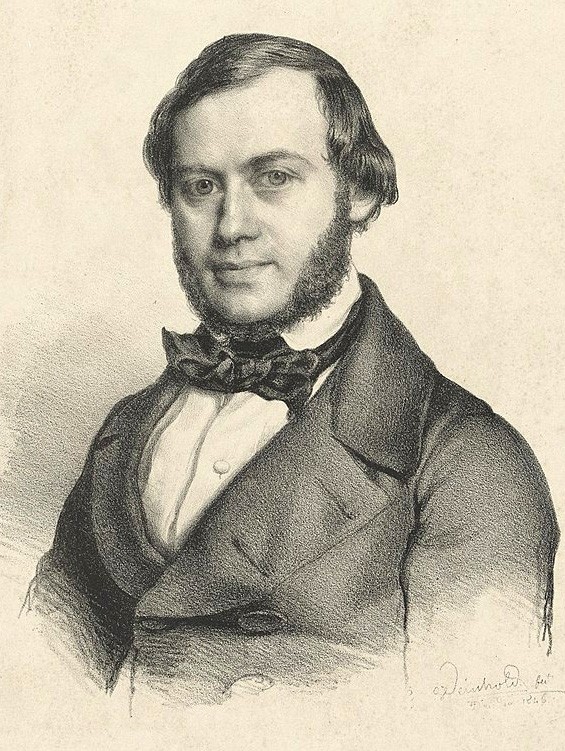

Strangely enough, Ferdinand David was born in exactly the same house in Hamburg where Felix Mendelssohn had been born the previous year. David was not a trombone player – few composers were. He was a violinist and being a pupil of the legendary Louis Spohr, a rather distinguished one at that. He was also a competent music editor who had a close working relationship with Breitkopf & Härtel and other publishers in Leipzig. This three-movement concerto is one of about fifty works which include five violin concertos. The work remains popular today with trombonists and it’s often used as an audition piece for those aspiring to get a job in a symphony orchestra. The composer calls it a concertino which literally means “a small concerto”. However, the word is sometimes used to indicate a work which is light-hearted in nature. The concerto dates from 1837 and opens lyrically with hints of Beethoven. It’s a lovely work, full of melodic invention and a brilliant trombone part superbly performed by the Israeli musician Nir Erez.

The music of the Danish composer Launy Grøndahl isn’t heard often these days, possibly because he was over-shadowed by Carl Neilsen, a Great Dane if ever there was one. Grøndahl began studying the violin at the age of eight and by the age of fifteen he was competent enough to become a professional player with the Orchestra of the Casino Theatre in Copenhagen, an orchestra known for its high standard. This concerto is Grøndahl’s best-known work and dates from 1924 when he was staying in Italy. Like countless concertos before and since, it is cast in the usual three movements and it’s an approachable and enjoyable work which in some ways seems to look back nostalgically to the late nineteenth century. This is especially true of the lyrical second movement, characterized by rich harmonies from the low brass. The movement contains some lovely melodic writing too. The work was composed a year before the composer became the resident conductor of the Danish National Symphony Orchestra, Denmark’s most prestigious orchestra. The concerto was originally written for symphony orchestra but several different instrumentations of the work exist and this version for trombone and wind orchestra is compelling.

|

|

|