Almost every afternoon I go down to our local market to buy food for the dogs and a small supply of jasmine rice. A country market in these parts would not be complete without background music although considering the volume at which it’s delivered “background” is not the first word that springs to mind. In our market there are three loudspeakers mounted on poles in different areas and they relentlessly belt out continuous and unrelated music. Two of them play Thai pop and a third plays selections of Isaan songs you were hoping never to hear again. I have no idea who is responsible and I’ve never felt compelled to follow the various cables to establish their source.

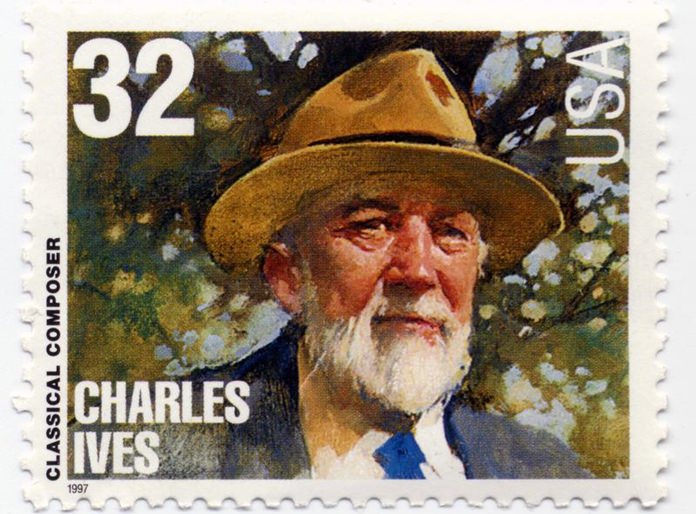

The other day, purely out of casual curiosity, I wandered about the market to try and find the exact spot where the sounds from each loudspeaker appeared to be the same volume. I found a convenient space near a stall where an owl-like woman was presiding over a large table of assorted plastic widgets, the purpose of which was not immediately obvious. In this position the three loudspeakers were equally balanced in volume. The curious experience of simultaneously hearing three unrelated songs reminded me of Charles Ives, whose birthday would have been this weekend. He would have probably relished my experience at the market.

Ives was born in Danbury, Connecticut where his father was a bandmaster. After a stint at Yale University the young Charles became one of the first American composers to engage in daring musical experiments which included using different keys at the same time, distorted rhythms, clusters of notes played together and elements of chance. Unfortunately all this proved too much of a challenge for most people and his music was generally ignored during his lifetime, largely on account of the relentless dissonance. Most of his music was composed before 1927 after which he felt, for reasons that have never really been discovered, that he could not compose anymore. For the rest of life he remained musically silent.

Today Charles Ives is recognized as “the grandfather of American music”. Leonard Bernstein recognized his genius and in 1951 conducted the premiere of the Second Symphony, an event which started to put Ives’ name on the musical map.

Ives was virtually self-taught and drew freely on American popular melodies, church music, patriotic tunes and marches, combining them in remarkable ways. His incredibly creative mind foreshadowed many of the innovations of the twentieth century. Three Places in New England was completed in 1914 and it’s one of his most popular orchestral works, containing many key features of his personal musical style.

The first movement is a haunting reflective piece; a memorial to the 54th Massachusetts Regiment many of whose members lost their lives during the Civil War. Ives creates a bleak sound-world in which out-of-focus shapes seem to drift across a dark, arid landscape. In contrast, the second movement Puttnam’s Camp (09:46) is enlivened with clashing harmonies and varying pulses combined to create the sound of community marching bands playing simultaneously. You’ll probably recognize some of the melodic fragments. The last movement opens with opulent and passionate harmonies which become increasingly strident before the works suddenly closes in almost total silence.

The Norwegian composer and pianist Geirr Tveitt (GAYR TVAYT) took a passionate interest in his country’s folk music and his birthday would have been this weekend too. His music draws on the barbaric style of Stravinsky’s early ballets, the rhythms and textures of Bartók’s music and the mystic qualities in the music of Debussy. His work was influenced Norwegian folk-music but by the 1950s anything that smacked of nationalism had become somewhat passé in Norway.

After years of international success, Tveitt’s music fell out of fashion and he became increasingly disenchanted, spending much of his time at the old family farm house with his unpublished manuscripts: five piano concertos, two violin concertos an opera, a couple of symphonies and a vast collection of folk-song arrangements. The music was filed in wooden boxes and it was a disaster waiting to happen. In 1970 the farm house burned to the ground, along with three hundred of Tveitt’s musical compositions. Tveitt was unscathed but eighty percent of his life’s work was lost forever.

The Fourth Piano Concerto has been reconstructed from the orchestral parts and recordings. The first movement was inspired by the aurora borealis and it’s a splendid, magical work with reflections of Debussy and Bartók and a gorgeously rhythmic second movement. Even so, I can’t help wondering what other remarkable music was lost to the world in that catastrophic fire.

|

|

|