On a question-and-answer website last week someone asked if he could become a professional violinist if he started lessons at the age of eighteen. He’d evidently not played the violin (or anything else) before. The response from several professional string players and teachers who took it upon themselves to answer was a resounding “no”. Of course, there’s no reason why you can’t start violin lessons at that age. You might even become passably good but you’d be pretty unlikely to ever reach a professional standard.

Violinist and teacher Sue Hunt claims that playing the violin is “the most complicated activity” known to humankind. It’s one of the reasons that top players start young. The Japanese teacher Shinichi Suzuki pioneered the notion that given the right musical environment, infants could learn to play the violin if the learning steps and the instrument were small enough. Some of his beginners were just two years old. This is unusually early and many string teachers consider the ideal age to be between three and five. However, an overwhelming passion to learn the instrument and the ability to concentrate are probably more important than the physical age.

The trouble is that there’s such a lot to learn. While the right hand has to develop a range of bowing skills, the left hand – not normally the one used for dexterous activity – has to do all the work producing the notes, sometimes in rapid succession. There is no visual guide on the fingerboard, so the position of every note has to be learned. Playing in tune is a skill in itself. And of course, playing the right notes in the right place is only half the story. It’s obvious that a range of musical and interpretational skills are also needed if the music is going to make any sense. Clearly, the sooner the child starts the better.

To qualify for any Music College at around the age of eighteen, students are required to be highly skilled musicians. Cellists for example, will be expected to be at a standard at which they can manage a half-decent performance of two particular works by Gabriel Fauré and Max Bruch. They’re staples of the cello repertoire and every student comes across them at some point. But they are both such wonderful works that studying them is a joy. Well, most of the time.

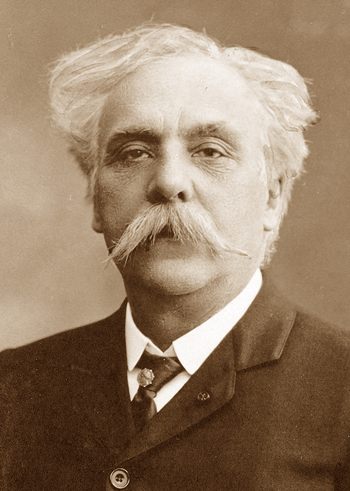

Fauré (FOR-ray) is today perhaps best-known for his Requiem and was one of the foremost French composers of his generation. In 1880, having just completed his First Piano Quartet, Fauré began work on a cello sonata and in his usual manner, started writing the slow movement first. For some reason the rest of the sonata was never completed and in 1883 the slow movement was published as a stand-alone piece called Élégie. The first performance was given the same year at the Société Nationale de Musique in 1883 and was such a great success that the conductor Édouard Colonne asked Fauré to write an arrangement for cello and orchestra. The arrangement was premiered in 1901; the legendary Pablo Casals was soloist and the composer conducted.

There are several fine recordings of this work from which to choose but this one, performed by young musicians from Wroclaw in Poland has excellent audio quality and you can clearly hear the expressive counter-melodies in the woodwind.

Strangely enough, at about the same time in 1880 that Fauré was writing his Élégie in Paris, Bruch was writing his Kol Nidrei (NEE-dry) in Liverpool. It was published in Berlin in 1881 and the title means “all vows” in Aramaic. It was one of the first pieces Bruch wrote when he took up the post of Principal Conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic, composed specifically for Liverpool’s Jewish community. It’s based on two Hebrew melodies, the first which is first heard on the solo cello and comes from the traditional service on the night of Yom Kippur.

Contrary to popular belief Bruch wasn’t Jewish himself but was friendly with several prominent Jewish musicians of the day. This evocative music shows Bruch at his best with lovely melodies sumptuously harmonized. This is a splendid performance and at 07:12 another melodious treat is in store, a plaintive Hebrew melody that forms the second subject of the work.

Cellist Matt Haimovitz was born in 1970 and started learning cello at an early age. He later studied with Leonard Rose at the Juilliard School. Rose described Haimovitz as “probably the greatest talent I have ever taught”. When this recording was made, he was just twenty-one and already a successful international musician.

|

|

|