All professional musicians know that string players tend to prefer the company of other string players. In an orchestra, they rarely mingle with anyone else. It’s not that string players are snobs you understand, they are just different. And I speak as an ex-string player myself. The cello, since you asked. The string section of a modern symphony orchestra often contains more musicians than the woodwind, brass and percussion put together. Brass players often like to joke amongst themselves that the string players are like a herd of sheep.

In my youth, in a cold grey country far, far away I used to play in youth orchestras. When I was about thirteen, I got a place in our county orchestra. But really, this was no great achievement. Our dog could have probably done the same thing if he’d persevered with the cello lessons.

Even way back then, the brass section of the orchestra seemed a rum lot. They were loutish, unrefined country lads and I think we string players were slightly scared of them. We never spoke to them of course. In later years, when I played in national orchestras it was much the same: the brass players were often rough types. But in those days, the brass section was a preserve of the males of the species. Even today, orchestral brass sections tend to be male dominated.

Musicologists prefer to call string instruments cordophones and it’s thought that the first bowed strings were probably developed in central Asia. In the history of music, the violin and its family are relative newcomers. They didn’t appear until the second half of the 16th century when the unrelated viol family held sway. The string orchestra has since become popular with composers with the result that there’s a surprisingly large repertoire. Some composers have written entire symphonies for strings alone.

A string orchestra usually contains between twelve and twenty-four musicians. They tend to be fairly small. The orchestras I mean, not the musicians. But because there are relatively few players, they can hear each other easily and often perform without a conductor. Like this one, for example.

There’s a clever bit of editing at the start of this video which took me rather by surprise. Camerata Nordica is Sweden’s leading string ensemble with most of its members from Scandinavian countries. You’ll probably notice instantly that there’s no conductor.

It might take you a few minutes to realize that there’s something else missing. Yes, it’s printed music. There’s not a sheet of music in sight and no untidy clutter of music stands. Apart from the two cellists all the players are standing. This, together with the fact that the musicians have memorized the music, makes for better eye-contact and therefore more secure ensemble playing. It also makes the performance more visually stimulating.

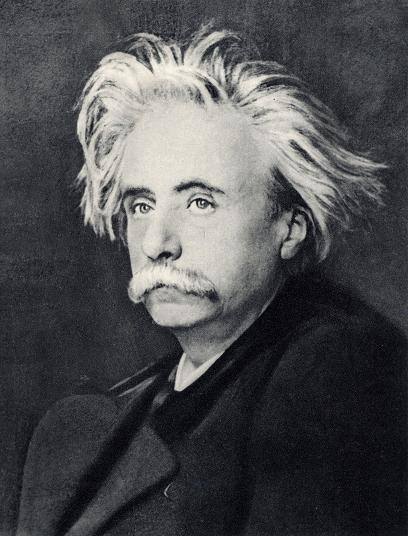

This delightful suite dates from 1884 and it was written to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of the philosopher and playwright Ludvig Holberg, considered one of Scandinavia’s most influential figures. Grieg wrote the work in an eighteenth century style using the dance forms of the period. In that sense, it’s an early example of neo-classicism. The suite was originally composed for piano but during the following year, Grieg skillfully arranged it for string orchestra. Even if this music is new to you, it’s possible you’ll recognise the Gavotte (06:20). You can look forward to some sparkling string playing in the last movement (15:17), a lively French baroque dance known as the Rigaudon.

The name Peter Warlock was actually the pseudonym of the British composer and acerbic music critic Philip Heseltine. The witch-like name reflected his obsession with all things occult. It was used for all his musical works, which include over a hundred songs, a number of choral works and a few instrumental pieces. He also wrote dozens of general music articles and reviews and contributed to many books.

The Capriol Suite dates from 1926 and it’s a set of six short dances. Like the Grieg, it would be described as neo-classical because it was loosely based on melodies from Arbeau’s Orchésographie, a sixteenth century manual of Renaissance dances.

Warlock was a curious figure in British music. He achieved notoriety through his unconventional and often scandalous lifestyle. He has been described an “alcoholic hell-raiser” but at least he wasn’t a brass player. Incidentally, I don’t want to give the impression that I have something against brass players. On the contrary, I have met several who are utterly charming. Or so they told me.

|

|

|