A few months ago, during those distant care-free days when we could wander the streets without surgical masks and sit in a bar with a glass of half-decent wine, I overheard some bloke at a nearby table remark loudly to his companion that he couldn’t stand poetry. “A waste of words” he snorted and implied in his dismissive comments that poetry was basically a load of arty-farty nonsense fit only for wimps and fairies. Poor old sod! He had no idea what he’s been missing.

I resisted the temptation to comment because I’ve found that if people tell you that they hate poetry, or hate ballet or hate asparagus, further discussion is pointless. They will never change their minds. Rather than become irritated with the poetry-hater, I dismissed his fatuous remarks on the grounds that he is the loser. He will never experience, let alone understand the joy of magical words.

Anyway, this all came to mind the other day when I was looking through a book of poems by that remarkable Bengali writer Rabindraneth Tagore. The book is entitled Gitanjali and inside the front cover is my mother’s maiden name followed by the inscription “Christmas 1934.” Looking through the yellowed pages and pouring over Tagore’s mystical verses, I was strangely reminded of what the English composer Henry Purcell wrote in 1650: “Musick and poetry have ever been acknowledged sisters, which walking hand in hand support each other; as poetry is the harmony of words, so musick that of notes…”

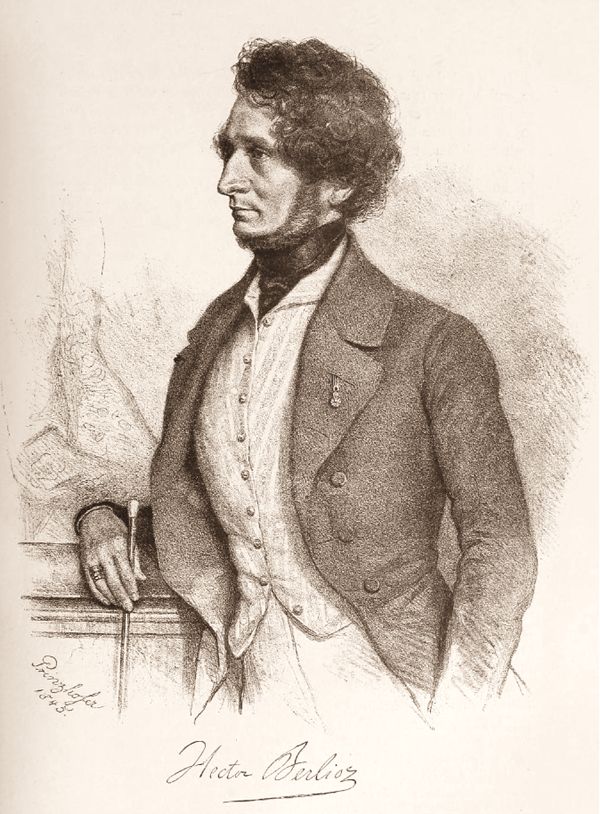

Music and poetry have indeed been intertwined for thousands of years. Even the first lyric poets in ancient Greece performed to the accompaniment of the lyre. From Elizabeth times until the 19th century, songs, music and poetry influenced each other in a kind of symbiotic, reciprocal kind of way. The art songs of the great 19th century song-writers were nearly always settings of existing poems. But even more interesting was the 19th century realization that poetry and literature could become the starting point for music. Berlioz and Liszt spring to mind as two of the many composers who turned to poetry. Richard Strauss drew heavily on German romantic poetry for his massive, brooding orchestral works. There must be hundreds of classical works that owe their existence to a poem. The English composers Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams often turned for inspiration to the poetry of the American writer Walt Whitman.

The evocative title of this work is from a poem by Whitman, whose writing influenced many young artists and musicians during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Vaughan Williams was fascinated by Whitman’s poetry and the collection of poems Leaves of Grass was a constant companion. The Sea Symphony of 1910, written for choir and orchestra uses Whitman’s poetry throughout. Toward the Unknown Region was intended as a companion piece for the symphony. It was actually finished before the symphony and first performed at the Leeds Festival in October 1907 with the composer conducting. He described it as a “song” for chorus and orchestra though it’s rarely performed today. This is a shame, for it’s a wonderful setting of the poem with superb choral writing, brilliant orchestration and soaring melodies. This performance, recorded at The Proms in 2013 is fresh and captivating with superb sound quality too. Try using a good quality headset to enjoy the expansive spatial audio of the recording.

Many years ago my mother confided in me that when she was a teenager, she loved to read the poetry of Lord Byron, until she heard that he was “one of those horrid perverts.” In fairness to Byron, I don’t suppose he was any more perverted than some of his other artistic chums. However, if this revelation titivates your sensibilities, I shall leave to explore the subject in your own time.

If you’re not familiar with this work, you might find the title mildly puzzling. The eponymous Harold was a character created by Byron and the subject of a lengthy, partly autobiographical poem completed in 1818 and entitled Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. It describes the travels and reflections of Harold, a somewhat world-weary young man who traipses around Europe looking for distraction in foreign lands. The word “childe” is a medieval title for someone who is a candidate for knighthood. Berlioz used Byron’s poem as a basis for the music, which he described as “a symphony in four parts with viola solo”. The viola reflects the character of Harold, the melancholy dreamer. Berlioz was good at writing memorable tunes and the solo viola enters with a remarkably beautiful melody (at 03:48) delicately accompanied by strings and harp. Completed in 1834, it’s all splendidly romantic music with a typically French lightness of touch. If Berlioz is new to you, here’s a rewarding place to start.

|

|

|