“Through Tara’s halls” I hear you murmur. Or perhaps I don’t, if you’re not familiar with the writings of that Irish poet, singer and songwriter Thomas Moore – not to be confused with Sir Thomas More, the English statesman who was eventually venerated in Catholicism as Saint Thomas More.

The song has certainly been around for long enough; since 1821 to be exact, when it was first published in a collection of Irish popular songs. The Irish Thomas Moore was born nine years after Beethoven and he’s best remembered for the lyrics of The Minstrel Boy, The Last Rose of Summer and other timeless songs. Tara, as you might (or might not) recall was the ancient seat of power in Ireland in prehistoric and early medieval times.

The harp is the traditional musical instrument of Ireland and symbolizes the Irish people and their culture. If you’ve ever tasted that splendid Irish dry stout called Guinness, you may have noticed the trade-mark image of a Celtic harp on every bottle. The harp is also the national instrument of Wales with a history that can be traced back at least to the eleventh century. It’s one of the oldest musical instruments in the world and simple harps, based loosely on the shape of a hunter’s bow were in use as early as 3500 BC. The large harp you see in orchestras today dates from the eighteenth century. It’s technically known as the pedal harp and has forty-seven strings covering a range of six-and-a-half octaves and weighs about eighty pounds.

An old chestnut among harp players is that harps are like old people; they’re unforgiving and difficult to get in and out of cars. As the name implies, the pedal harp has a set of pedals (seven, since you asked) which are connected to an ingenious internal mechanism which alters the pitch of the strings. Harps don’t come cheap. You can buy a student model for about $15,000 but a professional instrument could set you back over $100,000. You’ll also need to buy a big van to cart the thing around.

The harp is popular in Mexico, the Andes, Venezuela and Paraguay and although these instruments have slightly different designs, they have a common ancestor: the Baroque harps brought from Spain during the colonial period. Many classical composers have been attracted to the unique sound of the harp and there are perhaps surprisingly, a large number of harp concertos.

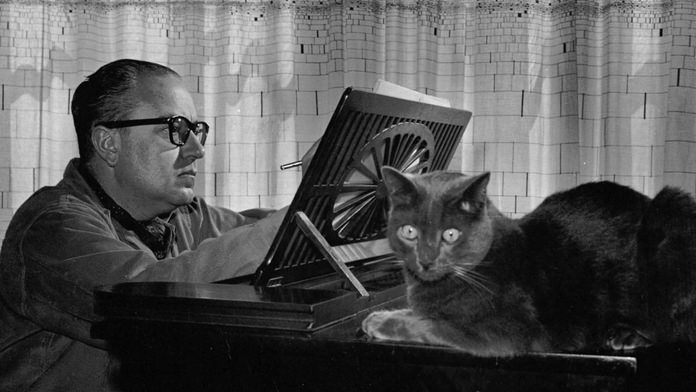

Alberto Ginastera (jee-nah-STEHR-ah) was the most influential composer of Argentine classical music. His music can be challenging, percussive, thrilling, thought-provoking and sometimes even downright scary.

This three movement concerto is a brilliant virtuosic work and it’s full of Ginastera’s musical trade-marks. The churning rhythms punctuated by thumps on the timpani at around 04:05 sound as though the passage has been lifted straight out of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Now I come to think about it, Stravinsky himself once remarked that “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.”

The frenetic music gradually transforms into the kind of mysterious musical landscape that Ginastera paints so well. The slow second movement takes the listener into a haunting sound-world of rich dark sonorities and strange angular melodies. The last movement (at 14:20) begins unusually with a cadenza which leads into a folk-like dance with sparkling rhythmic vivacity and catchy fragmented melodies. Driving rhythms lead the music into a thundering climax. It’s thrilling stuff and given a superb performance by both soloist and orchestra.

Nothing could be more different to the unbuttoned Ginestera concerto than this delightful work by one of the most prolific composers of the classical period. The Austrian composer Carl Dittersdorf wrote over two hundred symphonies, although some of them have not been authenticated. He wrote dozens of concertos, chamber works, oratorios, masses and operas: enough music to fill a small library. He was friends with Haydn and Mozart and with the composer Johann Baptist Wanhal they often played string quartets together. Dittersdorf’s three-movement Harp Concerto is a lovely work and exemplifies the classical ideals of form, elegance, grace and charm.

Harps have been the target for musicians’ jokes ever since the instrument appeared in the symphony orchestra. Unlike pianists, who expect the services of a piano tuner, harpists are expected to tune the instrument themselves. However, it quickly gets out of tune especially if there are temperature variations at the concert venue. The problem is summed up in a well-known orchestral joke, “How long does it take to tune a harp?” The answer is that nobody knows.

|

|

|