An acquaintance of mine is fond of remarking that “chamber music is musicians’ music” and while I think I know what he trying to say, it implies that chamber music is too refined for most listeners to grasp. This of course is utter nonsense. Honestly, he needs to be poked with a pointed wooden stick for saying such daft things. If I had one, I’d do it myself.

Needless to say, his own preference runs to massive orchestral works, grand opera and other gut-busting stuff. But you know, some of the finest, most expressive and most enjoyable music was written for just two or three instruments. A few monumental classics, such as Bach’s cello suites and his violin sonatas and partitas were written for only one. And so, were the countless memorable works for solo piano.

The expression “chamber music” implies something written for relatively few instruments which can be accommodated in a room rather than a concert hall. Technically speaking, it’s often defined as music in which each instrument has an individual part. For this reason, most musicians enjoy playing chamber music because unlike playing in an orchestra, they have complete artistic control over what they’re doing. To my mind the delight of chamber music is that every separate part is distinct, the harmonies shine more brightly and the counterpoint, when melodies are set against each other, is crystal clear.

A trio for example, can consist of any three instruments you care to name but over the years, several standard combinations have emerged. These include the String Trio (for violin, viola and cello) and the oddly named Piano Trio which is not, as some people might reasonably assume, music for three pianos. It’s nearly always for piano, violin and cello. Mozart wrote over twenty of them, and Haydn wrote forty-five. I have all Haydn’s on a set of CDs in the car, because with a total of ten hours playing time, there’s more than enough to help me endure the worst traffic jams that Bangkok has to offer.

Haydn, always one to be original, begins the work with piano and pizzicato strings, an unusual harp-like effect which recurs several times during the lyrical first movement. This three-movement trio was written in 1797 and is noted for its especially wide expressive range as well as its virtuosity. Although firmly rooted in the classical tradition, to my mind the first movement seems to look ahead to the romantic ideals of the approaching new century. In contrast, the second movement turns the clock back and sounds a bit like a passacaglia in which the mysteriously creeping bass part on the piano supports weaving melodic parts above. It sounds almost Bach-like. The last movement is more familiar ground – Haydn at his most elegant with playful and characteristic cross-rhythms intended to perplex and delight the ear.

This is a rewarding work; chamber music at its most intimate and satisfying and given a sensitive and telling performance by these fine Dutch musicians.

Looking through my database for this column I was surprised to find that I haven’t told you about this work before. I discovered it when I was a music student back in The Old Country and it’s always been one of my favourites.

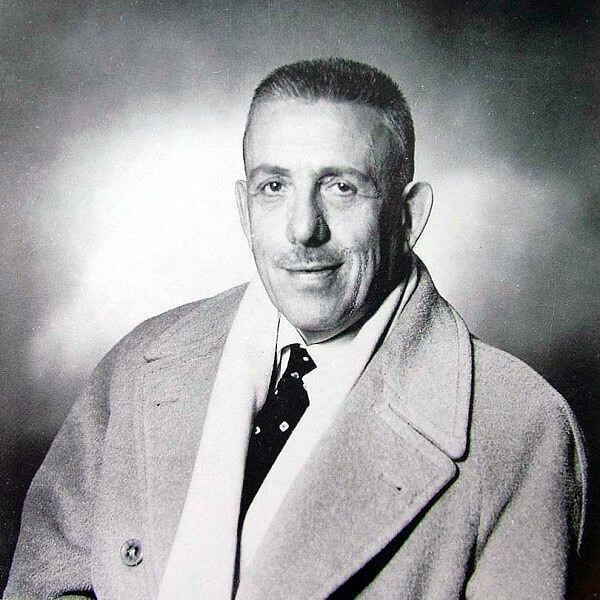

Although Poulenc (POO-lank) grew up in a musical household he was largely self-taught at composition. He later fell under the influence of Erik Satie and was one of the French composers collectively known as Les Six, a title that hardly requires translation. He’s probably best known for his Concert Champêtre (1928) for harpsichord and orchestra and the Gloria (1959) for soprano, choir and orchestra.

This trio was composed at Cannes in 1926, and dedicated to the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla, who evidently enjoyed it. The work begins with a series of serious-sounding chords on the piano, but soon the oboe and bassoon introduce an amusing scampering melody which forms the basis of the lively movement contrasted with typical Poulenc moments of soul-searching lyricism. The second movement is a beautifully-crafted piece that radiates tranquility and always reminds me of the pastoral river-side scenes in the classic book Wind in the Willows. It’s splendidly performed too. The colourful last movement is almost like looking through someone’s family photograph album, with its images of joy, fleeting glimpse of sadness, flashes of joyous hilarity and sudden moments of heart-tugging melancholy.

|

|

|