The English author Aidan Chambers once wrote, “I thought how lovely and how strange a river is. A river is a river, always there, and yet the water flowing through it is never the same water and is never still. It’s always changing and is always on the move. And over time the river itself changes too. It widens and deepens as it rubs and scours, gnaws and kneads, eats and bores its way through the land. Even the greatest rivers… the Nile and the Ganges, the Yangtze and the Mississippi must have been no more than trickles and flickering streams before they grew into mighty rivers.”

Battles have been fought over rivers or at least, close to them. The Battle of the Somme was a tragic episode during the First World War, involving British and French troops against those of the German Empire. The battle began in July 1916 and raged for over four months on both sides of the River Somme in France. By the following November, over a million soldiers had been killed or wounded.

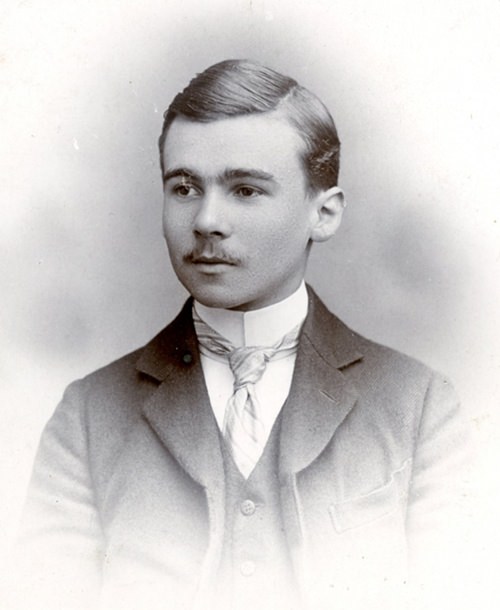

One of them was 31-year-old George Butterworth, a Lieutenant in the Durham Light Infantry who had already been awarded the Military Cross for bravery. On 5th August 1916 in the muddy trenches near the river, he was killed by sniper fire. Most of the other soldiers including his commanding officer were unaware that Butterworth was one of the most promising young English composers of his generation.

George Butterworth (1885-1916): The Banks of Green Willow. National Children’s Orchestra of Great Britain, cond. Roger Clarkson (Duration: 06:34; Video: 480p)

Although he was born in London’s Paddington district, the family soon moved to Yorkshire so that his father could take up an appointment as General Manager of the North Eastern Railway. The boy received his first music lessons from his mother and he began composing at an early age, playing the organ for services in the chapel of his elementary school. He won a scholarship to Eton College and later in life became a close friend of composer Ralph Vaughan Williams.

The Banks of Green Willow was written in 1913 and it’s a pastoral piece, based loosely on a folk song that Butterworth heard and wrote down in Sussex. It is probably the composer’s best-known work and the title implies a musical picture of a river somewhere in England, but we don’t know exactly where.

The work is given an engaging and lively performance by the National Children’s Orchestra of Great Britain, a well-established organization founded in 1978. Hearing these young musicians playing with such commitment and maturity it is hard to believe that they are all less than thirteen years old.

Like so much of the music by Delius and Vaughan Williams, this work sounds utterly English. It’s a picture of the England that Butterworth loved so much and for which, like so many others of his generation he fought for and paid for with his life.

Bedøich Smetana (1824-1884): Vltava. Gimnazija Kranj Symphony Orchestra, cond. Nejc Beèa (Duration: 14:40; Video: 1080p)

Unlike Butterworth’s meandering English river, we know exactly where this one is. It’s often called “the Czech national river”.

Bedøich Smetana is considered the grandfather of Czech music because he pioneered a national musical style. Má Vlast, meaning “My Homeland” is a set of six symphonic poems that Smetana wrote during the 1870s and one of the movements is called Vltava, also known by its German name Die Moldau. It describes the journey of the Vltava River from its source in the Bohemian mountains through the countryside to the city of Prague. The piece contains Smetana’s most famous melody, an adaptation of a borrowed Moldavian folksong which is strikingly similar to the tune of the Israeli national anthem.

This performance is by Gimnazija Kranj Symphony Orchestra, a youth orchestra based at Gimnazija Kranj high school in Slovenia. Established in 1810, the school is one of the oldest and most respected in the country and has over a thousand students between the ages of fifteen to eighteen. The orchestral playing is amazingly good and a remarkable technical and musical standard.

The piece begins with a musical picture of the springs at the source of the great river and eventually leads into the main theme. There are various musical snapshots during the work which include a sound image of a hunt in the forest, a peasant wedding, water-nymphs in the moonlight, St John’s Rapids and finally the concluding section in which the river triumphantly enters Prague and then flows away into the distance. It would be pleasing to tell you that the river eventually flows majestically to the sea, but it doesn’t. Further downstream, it merges with the River Elbe.

|

|

|