The Nation newspaper has reported that up to 26,000 people get killed in road accidents every year in Thailand, which puts the country sixth in terms of road casualties. Of those killed, up to 70 or 80 percent are motorcyclists or their passengers.

These statistics were released at a press conference by Vice Interior Minister Silapachai Jarukasemratana last week.

He told the press that the key causes for the deaths were speeding, drunk driving or the failure to wear safety belts or crash helmets – all of which are offences under traffic laws.

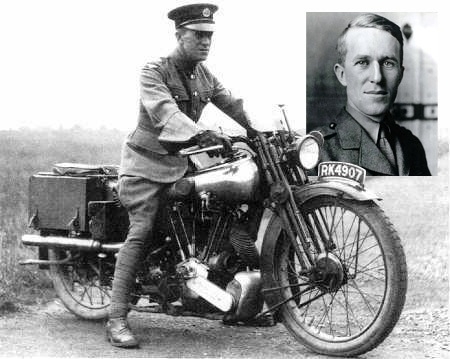

Lawrence of Arabia.

Lawrence of Arabia.

Now while I congratulate officialdom on keeping statistics, I can assure you that these are not the complete figures, as in Thailand, to be counted as a road death you have to die right there on the bitumen. Those who die later in hospital are not counted.

However, you don’t need to be an Einstein to see that if you attack the 70-80 percent, you would see a dramatic reduction in the road toll.

So why do motorcyclists get killed? It certainly isn’t from road-rash, but from brain damage, all of which can be reduced by the wearing of a proper helmet. This is not something new, but is something that has been proved all over the world for the past 80 years. Yes, 80 years, making Thailand quite behind the times.

However, it is interesting to look at the history surrounding the use of helmets, starting with motorcycle helmets, going back as far as T.E. Lawrence, otherwise known as Lawrence of Arabia, who died from brain injuries in 1935 following a motorcycle accident.

One of the neurosurgeons who attended Lawrence was Australian Dr. Hugh Cairns. He was profoundly moved by the tragedy of this famous First World War hero dying at such a young age from severe head trauma. Having been powerless to save Lawrence, Cairns set about identifying, studying, and solving the problem of head trauma prevention in motorcyclists.

In 1941, his first and most important article on the subject was published in the British Medical Journal. He observed that 2279 motorcyclists and pillion passengers had been killed in road accidents during the first 21 months of the war, and head injuries were by far the most common cause of death. Most significantly, however, Cairns had only observed seven cases of motorcyclists injured while wearing a crash helmet, all of which were nonfatal injuries. His 1946 article on crash helmets charted the monthly totals of motorcyclist fatalities in the United Kingdom from 1939 to 1945. The obvious decline in the number of fatalities took place after November 1941, when crash helmets became compulsory for all army motorcyclists on duty. His article concluded, “From these experiences there can be little doubt that adoption of a crash helmet as standard wear by all civilian motorcyclists would result in considerable saving of life, working time, and the time of hospitals.”

It was not until 1973, 32 years after his first scientific article on the subject, were crash helmets made compulsory for all motorcycle riders and pillion passengers in the United Kingdom. And many, many years after that for the use of crash helmets to be legislated in Thailand, and some SE Asian nations are yet to follow.

However, legislation alone is not enough. Helmets have to be of a sufficient standard to give the protection needed. The plastic bucket favored by some motorcycle taxi riders is worth very little as far as saving lives is concerned. There needs to be a standard, and the US Snell Foundation is one such organization, for example.

So what should be done here? The answer is two-fold. One -all helmets to be sold in Thailand have to meet international standards. Put a date on this such as Jan 1, 2014, so that shops can clear their current stocks. Very easy to police this by snap visits to stores selling helmets. And Two – the Thai Police have to crack down on the non-use of helmets by motorcycle riders and pillion passengers.

The latter is easy to do, and should not be just another revenue gathering for the BiB at the end of each month. The legislation is already there, enforce it properly.

If this were to be done, Vice Interior Minister Silapachai Jarukasemratana would be able to proudly announce a reduction in the road toll of at least 50 percent. But does the government have the tenacity and ‘will’ for this to happen?

Don’t hold your breath!