The publishing world appears to have a set of rules all its own. I will stop short of calling its conduct ‘subterfuge’, but I direct you towards that very core of the publishing business, the ISBN. A way to identify books which dates back to the 1967 version (called the SBN in the UK), and through to the International SBN and now the latest 13 digit classification. All very noble, and good to see that there has been international agreement on something at least.

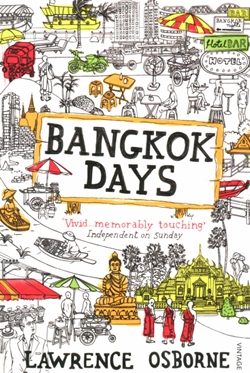

Let us now look at this week’s book from the Bookazine outlet that I have in my hand. Called Bangkok Days it was written by Lawrence Osborne and sports ISBN 978-0-099-53597-3. Published by Vintage Books in London in 2010, it sells for B. 395.

However, it was only when I came back to my office and went through my files that I found I had already reviewed a “Bangkok Days” written by a Lawrence Osborne (ISBN 978-1-846-55298-4) and published by Harvill Secker and released in 2009). It sold for B. 650. Could these be the same books? Surely not. The covers were entirely different, but inside, in miniscule print was the statement “First published in Great Britain in 2009 by Harvill Secker.” So the different ISBN numbers did refer to the one book, and with the change a sad commentary for the author that his work had been devalued from B. 650 to B. 395. That certainly lowered his income from royalties.

Previous books from Lawrence Osborne include The Accidental Connoisseur and The Naked Tourist, so he is no novice to the genre.

Bangkok Days is a narrative, with the author describing his (Bangkok) days as he explores the Thai capital on foot, claiming to be as poor as the proverbial temple dog.

Author Osborne has a keen eye and a full vocabulary. Describing his feelings after being told of a spirit inhabiting his garden he writes, “The mood suddenly changes. As the spirits move, a supernatural breeze stirs a chime, a bough, or a piece of grit against my tongue – and there for a second I feel them, shrilling like pipes in the distance, flickering in the dark with the mosquitoes.”

He deals at length with some of the other expats he meets, the Brit, the Aussie and the Spaniard. His eye examines his fellow expats finely. “Bangkok was filled with guys who played in unknown rock bands, ran bars, designed hotel toilets, but among them the fires of genuine ambition were not necessarily extinguished.” And one wonders whether that also described our author?

Amongst those who he meets and describes are Father Joe Maier and Sister Joan from the Klong Toey slums, two tireless workers who somehow have managed to retain a semblance of sanity whilst working in an environment that almost defies any sane logic.

However, Osborne is a gifted writer, but I felt the subject, with all its banality, was beneath him. As a travelogue, it didn’t need the salacious moments. It would have been better without it. He is a seriously good writer who should not trivialize his talents.