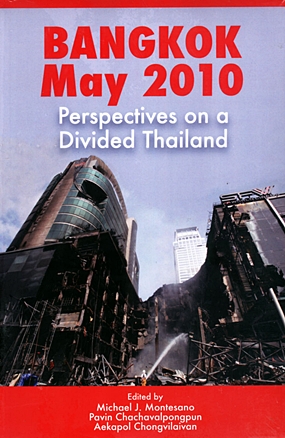

With recriminations still abounding from the Red and Yellow forces (and add in the Army), this book is well timed. Bangkok May 2010, subtitled Perspectives on a Divided Thailand is just available in Bookazine Big C Extra. The book was edited by Michael J Montesano, Pavin Chachavalpongpun and Aekapol Chongvilaivan (ISBN 978-616-215-042-5, Silkworm Books, 2012) and those three writers have also contributed to some chapters.

To try and ensure a balance between Red and Yellow preferences, the book is made up of items/articles/blogs from 26 writers, with many from tertiary institutions within and outside of Thailand.

In Montesano’s Introduction he writes, “Scholars may treat the ongoing conflict between Red and Yellow as Asia’s first major violent revolution – whether triumphant or extinguished – of the young century. They may see it as the sad end to a royal reign that looked so successful for so long. Or they may determine that it was due to the greed, cynicism, and evil of Thaksin Shinawatra alone.”

In the third chapter, James Stent writes, “The tragedy is Thaksin proved to be a false prophet, a venal and egotistical demagogue who had realized the potential power of the rural voting masses, but did not use this insight genuinely to reform the nature of Thai society.”

The concept of the ruling elite (ammat) versus the poor peasant (phrai) is a wonderfully emotive way to look at what happened in May 2010, but is far too simplistic, and this is ably shown throughout the book. Many graphs are printed to attempt to show where the support groups lay, and it is obvious that “reds” was not a cohesive slice of the Thai population and many factors smudged the edges, including the cash hand-outs for the demonstrators from the bottomless piggy bank held by Thaksin Shinawatra.

Examination of the May 2010 conflict automatically brings up (or dredges up) the massacre of 1992, and no attempt to suppress this is done in this book. There are more than passing similarities, and much of this can be explained by Thai culture/society. This is dealt with by more than one author of the chapters.

This book was a brave undertaking right from the outset, as the internal struggles are far more than a democracy trying to make itself apparent. It is also not a condemnation of what has gone before the Thaksin years, the patronage system, Bangkok versus Isaan Thai and other popular concepts such as the lese majeste provisions in the legal code and the vexed question as to whom is the next to succeed HM King Bhumibol. The book offers no real definitive answers, but does bring forth several points to ponder, far more than the surface battle of the colors.

A weighty tome and good value for anyone with an eye to the future – the future of Thailand itself. The back cover says it all, “Contributions examine socio-economic, political, diplomatic, historical, cultural and ideological issues with rare frankness, clarity and lack of jargon.” The only omission to this book is the fact that the red sympathizers are now in power, and Thaksin’s younger sister is the PM.