Now then, I wonder if you can reel off a list of Latin-American composers. If this seems a daunting task, don’t let it bother you too much because I suspect that few people in these parts can accomplish such a feat. Many concert-goers in Europe would find themselves in a similar position although some could probably dredge up the names of the Brazilian Villa-Lobos and possibly the Mexican composer Carlos Chavez. There are dozens of others whose music is frequently performed in Latin America but it has been slow to penetrate the rest of the classical music world. But honestly, I don’t know why.

Please Support Pattaya Mail

Out of curiosity, I dug out my 2002 edition of the venerable Oxford Companion to Music. The entire history of Latin-American music is summed up in three pages. In contrast, Johannes Brahms gets four pages and Beethoven gets five. Villa-Lobos, who wrote over a thousand works, gets just two paragraphs. This less-than-subtle Eurocentric perspective is to me at least, deeply disturbing. It may have been valid during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but now the world is a different place.

Recently the conductor Gisele Ben-Dor wrote in Symphony magazine, “Listen to some Latin-American composers and you’re going to find treasures. Keep digging… I think we need to discover music that we didn’t know before – new music, even if it’s old.”

Although there are some examples of early Latin-American music, the twentieth century has seen an explosion of composing activity. Many Latin-American composers write music which is intensely rhythmic, drawing freely on elements of national folk dance.

If you find yourself at a loose end one day, try typing a few names into the YouTube search box, followed by the word “composer”. For a start, you could try Leo Brouwer (Cuba), Silvestre Revueltas or Rodolfo Halffter (Mexico), José Serebrier (Uruguay) or Astor Piazzolla (Argentina). Oh yes, then there’s Oscar Lorenzo Fernández, one of the older school of twentieth century Brazilian composers. He eventually became a distinguished music teacher and founded the Brazilian Conservatory of Music in which he served as Director.

Like the nineteenth century French composer Hector Berlioz, Fernández first studied medicine, but was eventually drawn to music and moved through the Rio de Janeiro musical establishment, at first basing his music on European models. In 1924 Fernández won a composing competition with a piano trio entitled Trio Brasileiro, a work infused with elements of Brazilian popular song and dance. Most of his subsequent works, which include two symphonies, five symphonic poems and a handful of concertos, are decisively Brazilian in character and frequently quote folksongs.

In the early 1930s he wrote a three-act opera, entitled Malazarte which is a colourful, nationalistic work and thought to be the first successful Brazilian opera of its type. As composers so often do, Fernández extracted a three-movement suite from the opera, the last one of which, Batuque has become especially popular. This lively percussion-driven piece is based on an Afro-Brazilian folk dance. It uses pulsating and pounding rhythms and seems to give a foretaste of the minimalist movement yet to come.

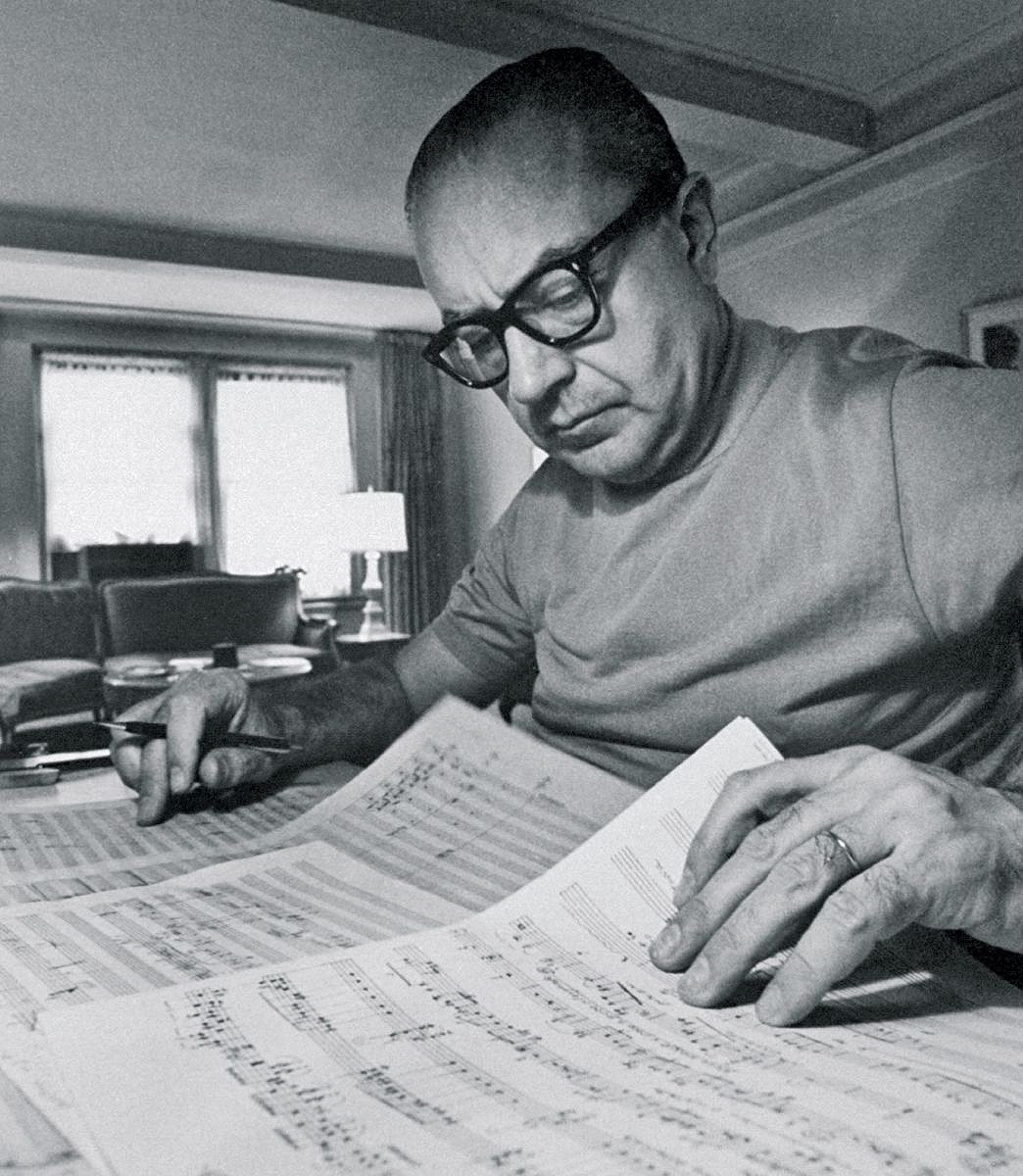

Alberto Ginastera (jee-nah-STEHR-ah) is considered the most powerful voice in Argentine classical music. He studied at the conservatoire in Buenos Aires, and later with the American composer Aaron Copland. Ginastera’s music can be challenging, percussive, thrilling, thought-provoking and sometimes even downright scary. If anything sums it up, the word is rhythm.

Much of Ginastera’s music draws on Argentine folk themes or other elements of traditional music. He greatly admired the Gaucho traditions and this is reflected in his 1942 one-act ballet Estancia (“The Ranch”). Ginastera turned the ballet music into a delightful four-movement orchestral suite and if you haven’t heard his music before, this is a great place to start. All the hallmarks of his style are here: his passion for percussive sounds, his sparkling angular melodies and of course his infectious sense of rhythm.

This is an absolute “must hear”. The closing section (at 10:47) is thrilling, with cataclysmic percussion and brilliantly articulated playing. The Simon Bolivar Orchestra of Venezuela is the product of another music teacher, José Antonio Abreu, who developed the music education programme known as El Sistema.

And by the way, the Gershwin song ungrammatically entitled I Got Rhythm was published in 1930 and was written in the surprisingly unusual key of D flat. I don’t know whether you’ve noticed, but the second phrase is the same as the first, played backwards.

|

|

|