The German writer and dramatist August von Kotzebue once wrote in the magazine Der Freimütige, “All impartial musicians and music lovers were in perfect agreement that never was anything so incoherent, shrill, chaotic and ear-splitting produced in music. The most piercing dissonances clash in really atrocious harmony and a few puny ideas only increase the disagreeable and deafening effect.” The year was September 1806 and Kotzebue was referring to Beethoven’s overture Fidelio. Incidentally, Kotzebue was murdered thirteen years later but not, surprisingly by Beethoven.

Samuel Butler once wrote, “The only things we really hate are unfamiliar things”. We know how children can be squeamish about unfamiliar foods and suspicion surrounding the unfamiliar can pass well into adulthood and even old age. In his book Lexicon of Musical Invective (from which the two above quotations are taken) musician and writer Nicolas Slonimsky describes this phenomenon as “non-acceptance of the unfamiliar”. Look at any newspaper and you can see this phenomenon at work every day, whether in music, art, science or religion.

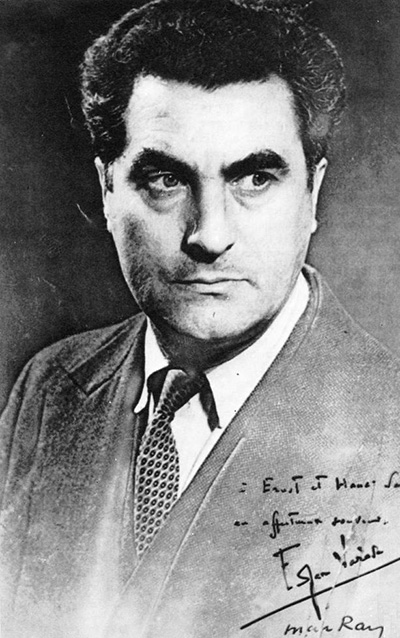

In 1915 the French composer Edgar (or Edgard) Varèse arrived in New York from Europe. Soon afterwards, he wrote his first American composition entitled Amériques which was later premiered at Carnegie Hall in April 1926 by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski. The music critic of the New York Times wrote, “No sooner had the last of the strange sounds of Mr. Varèse disappeared in the silence when the audience commenced to demonstrate: to hiss, to applaud, to gesticulate, even to whistle and bawl.”

Amériques has been described as “a musical picture of the machine age” with sounds which evoke the clatter of New York’s railways, the hooting of foghorns on the Hudson River and the incessant wailing of police-car sirens. It’s scored for a massive orchestra with double woodwind and brass and also requires a large percussion section with exotic instruments such as sleigh bells, a cyclone whistle, a steamboat whistle, a twig brush and a crow call. In case you’re wondering, the crow call sound is made by squeezing the mouthpiece with your teeth while blowing into the instrument.

The work is full of strikingly dissonant sounds and extremely complex rhythmic patterns built up using blocks of sound with short motifs juxtaposed against each other. Varèse used unconventional techniques and instrumental effects and about two thirds of the way through the work a strange hypnotic dance emerges with repeated figure in the strings and a haunting melody in the upper winds.

The sheer elemental power of the work is exhilarating but I have to admit that this music will not be to everyone’s taste. Varèse was opening up a new sound world and, to quote the voiceover of a famous television series, he was attempting to “boldly go where no one had gone before”.

Dating from 1967, this is a powerful, brooding work in which Ligeti takes us by the hand (or, more accurately by the ear) and leads us into an alien, uncharted territory. Perhaps this is one of the reasons Stanley Kubrick used Ligeti’s music in his seminal movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. But this music doesn’t actually describe anything in the sense that Smetana’s Vltava describes a river, or Debussy’s La Mer evokes images of the sea. Lontano begins almost inaudibly with a single A flat on the flute, then gradually other instruments enter playing the same note. They’re joined by the trumpets but then the woodwinds move one by one down to G, thereby creating an increasingly cutting dissonance. If you’ve not heard this piece before, your first reaction might be, “What’s going on here?”

György Ligeti (jurj LIH-geh-tee) explained that – “the harmonic crystallization within the area of sonority leads to an intervallic-harmonic thought process… achieved with the aid of polyphonic methods: the fictive harmonies emerge from the complex vocal woven texture and the gradual opacity and new crystallization are the result of discrete alterations in the individual parts”. Perhaps it makes more sense in the original Hungarian. He seems to be saying that many horizontal threads of simultaneous melody sometimes combine to produce brief moments of recogniseable harmony.

From time to time, a familiar-sounding chord emerges through the rich texture then fades away as quickly as it appeared, tantalizingly out of reach. I have always loved Lontano and find it immensely satisfying. Perhaps at first hearing it sounds as though the music is happening by chance, but it is actually incredibly detailed and precise in its notation. The score contains many specific written instructions and interestingly, the piece ends with a silent bar which lasts between ten and twenty seconds. Not many people know that.

|

|

|