Some years ago, UK’s Classic FM radio station published a list of what was considered the “saddest music ever written”. It contained the well-known lament from Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas. This incidentally, was my very first professional engagement, not singing the role of Dido you understand, but playing the cello in the orchestra.

The Classic FM list also contained some instrumental works which included the slow movement from Elgar’s Serenade for Strings, Albinoni’s Adagio and the slow movement of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony. Then there was the slow movement from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, which leapt to fame after Luchino Visconti used it his 1971 movie Death in Venice.

As a young teenager I remember becoming hopelessly weepy every time I listened to the yearning slow movement of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto, though I could never understand the reason. When you look at the score, the melodic line looks straightforward enough but somehow, the wandering theme hits the button, especially when it’s taken up by the strings. The music isn’t actually sad. If anything, it’s elevating and enriching and at some moments, filled with joy.

Charles Darwin noted that “several of our strongest emotions – grief, great joy, and sympathy – lead to the free secretion of tears and it is not surprising that music should be apt to cause our eyes to become suffused with tears”. Darwin realised of course that music doesn’t have to be “sad” to bring out powerful emotions. In any case, the word “sad” is far too childishly simplistic to be of much value.

I recently came across a fascinating article on the subject by Robert Barry, amusingly entitled Having a Bawl in which he wrote, “There are tears and then there are tears. Emotional tears, the ones wrung from inner pain and the recognition of tragedy, have even a different chemical composition. There are proteins that are theirs alone. And the precise network of higher brain functions involved in these less obviously functional emissions remains shrouded in mystery.”

It’s sometimes been suggested that a minor key can produce a “sad” effect but I don’t think that explanation holds much water, or much of anything for that matter. The song My Favourite Things is in a minor key and it’s anything but sad. The Rachmaninov movement which made me lachrymose as a teenager is in a major key. And so for that matter is the last movement of Mahler’s massive Third Symphony which is almost guaranteed to bring a tear or three. But whether it’s a tear of melancholy, sadness, joy, elation or ecstasy, I shall leave it to you to decide.

This final movement, undeniably introspective and poignant is in the bright sunny key of D major. The symphony was composed between 1893 and 1896 and it’s probably the longest symphony ever written, running for about an hour and a half. The work is scored for an enormous orchestra too, with the result that it’s played less often than Mahler’s other symphonies.

Unusually, it has six movements instead of the more conventional four. In a letter to a friend, Mahler referred to the work as “A Summer’s Midday Dream” and he gave each movement a fanciful title implying that they were mildly descriptive. However, before the symphony was published in 1898, he ditched all the titles, indicating that he must have had a major change of heart.

The conductor Bruno Walter wrote, “In the last movement, words are stilled, for what language can utter heavenly love more powerfully and forcefully than music itself?” The broad sweeping lines of the melodies touch the emotions in all sorts of ways and seem to grow organically, beginning very softly with a hymn-like melody which slowly builds to a loud, majestic and triumphant conclusion.

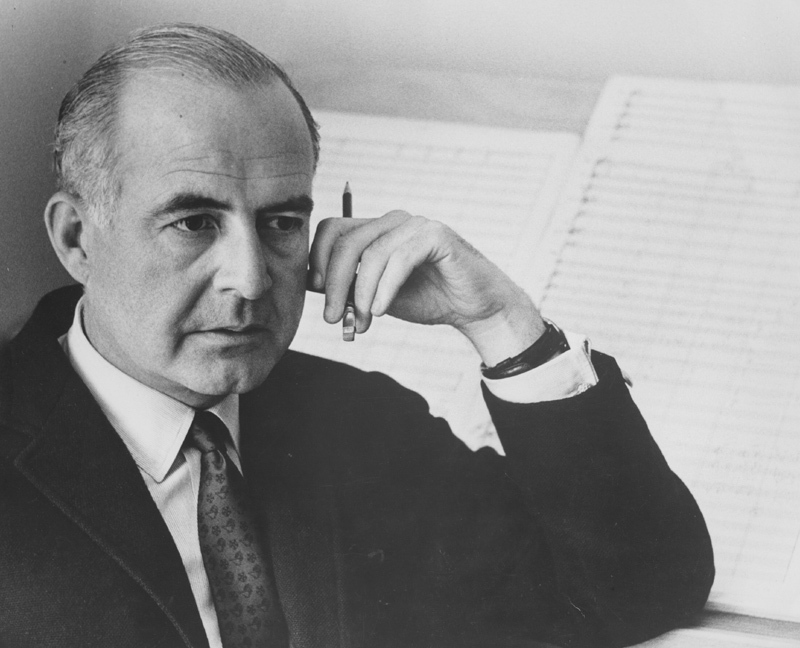

Barber was one of America’s most celebrated composers of the twentieth century. This piece was originally the slow movement of his String Quartet in B minor, written in Austria during 1935 and 1936. It would have probably remained obscure had not the conductor Arturo Toscanini urged Barber to arrange it for orchestra. It has since become hugely popular and been used in several feature films.

When the BBC launched a competition to find the “saddest music in the world”, Barber’s Adagio came at the top of the list. However, the word “sad” in this context is another over-simplification, for the music has moments of joy and triumph. Incidentally, the Italian word “adagio” simply means “slowly” and this is an intense work which grows in power and volume from the beginning. Notice how the melody develops and how Barber uses silence for dramatic effect in the long pause after the climax at 05:58. For a moment, it seems like the end of piece. But it isn’t. Instead, the composer takes us back to that quiet, secretive place where our melancholy journey began.

|

|

|