We’re doing so much more than eradicating polio.

Musa Muhammed Ali, a farmer in Borno state, Nigeria, has had to deal with the many ways polio has affected his life. For instance, he used to have to pay for transportation when he needed to buy feed for his animals. But after receiving a hand-operated tricycle funded through Rotary’s PolioPlus grants, Ali (pictured above) can now spend that money on other necessities. His life was changed by the “plus” in PolioPlus.

When we talk about PolioPlus, we know we are eradicating polio, but do we realize how many added benefits the program brings? The “plus” is something else that is provided as a part of the polio eradication campaign. It might be a hand-operated tricycle or access to water. It might be additional medical treatment, bed nets, or soap. A 2010 study estimates that vitamin A drops given to children at the same time as the polio vaccine have prevented 1.25 million deaths by decreasing susceptibility to infectious diseases.

In these pages, we take you to Nigeria, which could soon be declared free of wild poliovirus, to show you some of the many ways the polio eradication campaign is improving lives.

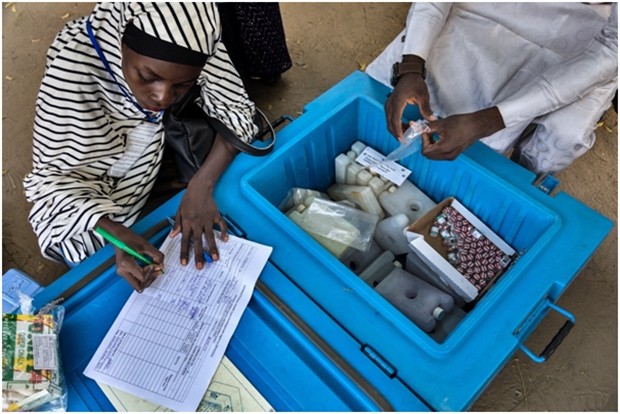

PREVENTING DISEASE

Polio vaccination campaigns are difficult to carry out in northern Nigeria, where the Boko Haram insurgency has displaced millions of people, leading to malnutrition and spikes in disease. When security allows, health workers diligently work to bring the polio vaccine and other health services to every child, including going tent to tent in camps for displaced people. The health workers pictured here are in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno, where the insurgency began 10 years ago.

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), of which Rotary is a spearheading partner, funds 91 percent of all immunization staff in the World Health Organization’s Africa region. These staff members are key figures in the fight against polio — and other diseases: 85 percent give half their time to immunization, surveillance, and outbreak response for other initiatives. For example, health workers in Borno use the polio surveillance system, which detects new cases of polio and determines where and how they originated, to find people with symptoms of yellow fever. During a 2018 yellow fever outbreak, this was one of many strategies that resulted in the vaccination of 8 million people. And during an outbreak of Ebola in Nigeria in 2014, health workers prevented that disease from spreading beyond 19 reported cases by using methods developed for the polio eradication campaign to find anyone who might have come in contact with an infected person.

Children protected from polio still face other illnesses, and in Borno, malaria kills more people than all other diseases combined. Worldwide, a child dies of malaria every two minutes. To prevent its spread, insecticide-treated bed nets — such as the one Hurera Idris is pictured installing in her home — are often distributed for free during polio immunization events. In 2017, the World Health Organization, one of Rotary’s partners in the GPEI, organized a campaign to deliver antimalarial medicines to children in Borno using polio eradication staff and infrastructure. It was the first time that antimalarial medicines were delivered on a large scale alongside the polio vaccine, and the effort reached 1.2 million children.

Rotary and its partners also distribute soap and organize health camps to treat other conditions. “The pluses vary from one area to another. Depending on the environment and what is seen as a need, we try to bridge the gap,” says Tunji Funsho, chair of Rotary’s Nigeria PolioPlus Committee. “Part of the reason you get rejections when you immunize children is that we’ve been doing this for so long. In our part of the world, people look at things that are free and persistent with suspicion. When they know something else is coming, reluctant families will bring their children out to have them immunized.”

Rotarians’ contributions to PolioPlus help fund planning by technical experts, large-scale communication efforts to make people aware of the benefits of vaccinations, and support for volunteers who go door to door.

Volunteer community mobilizers are a critical part of vaccination campaigns in Nigeria’s hardest-to-reach communities. The volunteers are selected and trained by UNICEF, one of Rotary’s partners in the GPEI, and then deployed in the community or displaced persons camp where they live. They take advantage of the time they spend connecting with community members about polio to talk about other strategies to improve their families’ health. Fatima Umar, the volunteer pictured here, is educating HadizaZanna about health topics such as hygiene and maternal health, in addition to why polio vaccination is so important.

Nigerian Rotarians have been at the forefront of raising support for Rotary’s polio efforts. For example, Sir Emeka Offor, a member of the Rotary Club of Abuja Ministers Hill, and his foundation collaborated with Rotary and UNICEF to produce an audiobook called Yes to Health, No to Polio that health workers use.

PROVIDING CLEAN WATER

Addressing a critical long-term need such as access to clean water helps build relationships and trust with community members. Within camps for displaced people, vaccinators are sometimes met with frustration. “People say, ‘We don’t have water, and you’re giving us polio drops,’” Tunji Funsho explains. Rotary and its partners responded by funding 31 solar-powered boreholes to provide clean water in northern Nigeria, and the effort is ongoing. At left, women and children collect water from a borehole in the Madinatu settlement, where about 5,000 displaced people live.

Supplying clean water to vulnerable communities is a priority of the PolioPlus program not only in Nigeria, but also in Afghanistan and Pakistan — the only other remaining polio-endemic nations, or countries where transmission of the virus has never been interrupted. “Giving water is noble work also,” says Aziz Memon, chair of Rotary’s Pakistan PolioPlus Committee.

Access to safe drinking water is also an important aspect of the GPEI’s endgame strategy, which encourages efforts that “ensure populations reached for polio campaigns are also able to access much-needed basic services, such as clean water, sanitation, and nutrition.” The poliovirus spreads through human waste, so making sure people aren’t drinking or bathing in contaminated water is critical to eradicating the disease. Bunmi Lagunju, the PolioPlus project coordinator in Nigeria, says that installing the boreholes has also helped prevent the spread of cholera and other diseases in the displaced persons camps.

Communities with a reliable source of clean water enjoy a reduced rate of disease and a better quality of life. “When we came [to the camp], there was no borehole. We had to go to the nearby block factory to get water, and this was difficult because the factory only gave us limited amounts of water,” says Jumai Alhassan (pictured at bottom left bathing her baby). “We are thankful for people who provided us with the water.”

CREATING JOBS

Polio left Isiaku Musa Maaji disabled, with few ways to make a living. At age 24, he learned to build hand-operated tricycles designed to provide mobility for disabled adults and children, and later started his own business assembling them. His first break came, he says, when a local government placed a trial order. It was impressed with his product, and the orders continued. Rotary’s Nigeria PolioPlus Committee recently ordered 150 tricycles from Maaji to distribute to polio survivors and others with mobility problems. The relationship he has built with local Rotarians has motivated him to take part in door-to-door polio vaccination campaigns.

“It is not easy to be physically challenged,” he says. “I go out to educate other people on the importance of polio vaccine because I don’t want any other person to fall victim to polio.”

Aliyu Issah feels lucky; he’s able to support himself running a small convenience store. He knows other polio survivors who have attended skills training programs but lack the money to start a business and are forced to beg on the street. However, the GPEI provides a job that’s uniquely suited to polio survivors: educating others about the effects of the disease.

“Some of my friends who used to be street beggars now run their own small business with money they earn from working on the door-to-door immunization campaign,” Issah says.

IMPROVING HEALTH CARE

In Maiduguri, Falmata Mustapha rides a hand-operated tricycle donated to her by Rotary’s Nigeria PolioPlus Committee. She is joined by several health workers for a door-to-door immunization campaign, bringing polio drops to areas without basic health care. UNICEF data show that polio survivors like Mustapha have a remarkable success rate persuading reluctant parents to vaccinate their children — on average, survivors convince seven of every 10 parents they talk to. In places where misinformation and rumors have left people hesitant to vaccinate, the survivors’ role in the final phase of the eradication effort is critical.

“Since working with the team, I have seen an increase in immunization compliance in the community,” Mustapha says. “I am well-regarded in the community because of my work, and I am happy about this.”

Eighteen million people around the world who would have died or been paralyzed are alive and walking because of the polio eradication campaign. Health workers and volunteers supported by PolioPlus grants have built an infrastructure for delivering health care and collecting data that, in many parts of the world, didn’t exist before. It’s already being used to improve overall health care and to fight other diseases, proving that the legacy of PolioPlus is more than eradicating a deadly disease from the planet — it’s also building a stronger health system that provides better access to lifesaving interventions for the world’s most vulnerable children.

This story originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of The Rotarian magazine.

The polio eradication campaign needs your help to reach every child. Thanks to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, your contribution will be tripled. To donate, visit endpolio.org/donate.