Chicago (AP) — Newer drugs are substantially improving the chances of survival for some people with hard-to-treat forms of lung, breast and prostate cancer, doctors reported at the world’s largest cancer conference.

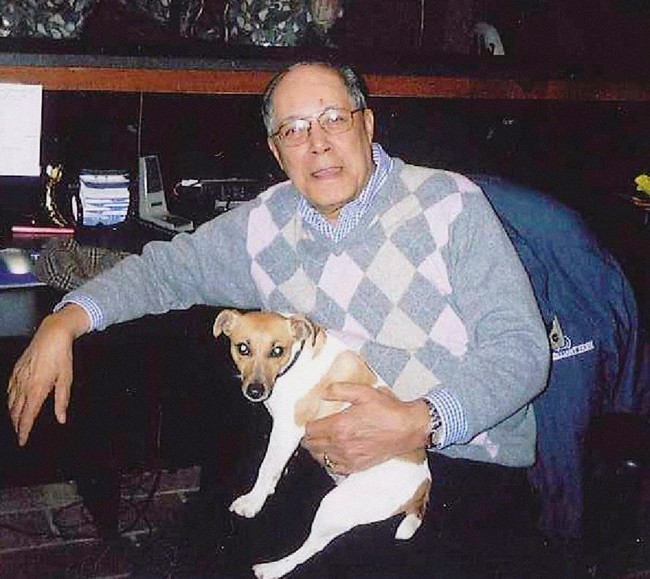

Among those who have benefited is Roszell Mack Jr., who at age 87 is still able to work at a Lexington, Kentucky, horse farm, nine years after being diagnosed with lung cancer that had spread to his bones and lymph nodes.

“I go in every day, I’m the first one there,” said Mack, who helped test Merck’s Keytruda, a therapy that helps the immune system identify and fight cancer. “I’m feeling well and I have a good quality of life.”

The downside: Many of these drugs cost $100,000 or more a year, although what patients pay out of pocket varies depending on insurance, income and other criteria.

The results were featured Saturday and Sunday at the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference in Chicago and some were published by the New England Journal of Medicine. Companies that make the drugs sponsored the studies, and some study leaders have financial ties.

Here are some highlights:

Lung Cancer

Immunotherapy drugs such as Keytruda have transformed the treatment of many types of cancer, but they’re still fairly new and don’t help most patients. The longest study yet of Keytruda in patients with advanced lung cancer found that 23% of those who got the drug as part of their initial therapy survived at least five years, whereas 16% of those who tried other treatments first did.

In the past, only about 5% of such patients lived that long.

“I’m a big believer that it’s not just about duration of life, quality of life is important,” said Dr. Leora Horn, of the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville, Tennessee. She enrolled Mack in the 550-person study.

Mack said he had manageable side effects — mostly some awful itching — after starting on Keytruda four years ago. He went off it last winter and scans showed no active cancer; he and his doctor hope it’s in remission.

Last year, a smaller study reported five-year survival rates of 16% for similar patients given another immunotherapy, Opdivo.

“From both studies we’re getting a similar message: When these drugs work, they can have a really durable effect,” Horn said.

Breast Cancer

The risk of this rises with age, but about 48,000 cases each year in the U.S. are in women under age 50. About 70% are “hormone-positive, HER2-negative” — that is, the cancer’s growth is fueled by estrogen or progesterone and not by the gene that the drug Herceptin targets.

In a study of 672 women with such cancers that had spread or were very advanced, adding the Novartis drug Kisqali to the usual hormone blockers as initial therapy helped more than hormone therapy alone.

After 3 1/2 years, 70% of women on Kisqali were alive, compared to 46% of the rest. Side effects were more common with Kisqali.

This is the first time any treatment has boosted survival beyond what hormone blockers do for such patients.

Prostate

The options keep expanding for men with prostate cancer that has spread beyond the gland. Standard treatment is drugs that block the male hormone testosterone, which helps these cancers grow, plus chemotherapy or a newer drug called Zytiga.

Now, two other drugs have proven able to extend survival when used like chemo or Zytiga in men who were getting usual hormone therapy and still being helped by it.

One study tested Xtandi, sold by Pfizer and Astellas Pharma Inc., in 1,125 men, half of whom also were getting chemo. After three years, 80% of those given Xtandi plus standard treatments were alive, compared to 72% of men given the other treatments alone.

The other study involved 1,052 men who were given hormone therapy with or without the Janssen drug Erleada. After two years, survival was 82% among those on Erleada and 74% among those who weren’t.

Men now have a choice of four drugs that give similar benefits, and no studies yet have compared them against each other, said Dr. Ethan Basch, a prostate specialist at the University of North Carolina’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center who has no financial ties to any drugmakers.

Cost and side effects may help patients decide, he said. Chemo can cause numbness and tingling in the hands and feet and may not be good for men with diabetes who already are at higher risk for this problem. Zytiga must be taken with a steroid; Xtandi and Erleada can cause falling and fainting.

Chemo has more side effects but costs much less and requires only four to six intravenous treatments. The other three drugs are pills that cost more than $10,000 a month and are taken indefinitely.

“I have patients who refuse to take these drugs because of cost,” Basch said. “Patients have more choice, but it isn’t clear more benefit is being provided” beyond what chemo gives, he said.

|

|

|