Loving Father of heartbroken nation

The Pattaya Mail Media Group joins the entire Kingdom in sorrowfully extending our heartfelt grief in the passing of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej who passed away in peace on October 13, 2016. We wish to join all people of the world in our most sincere condolences to the entire Royal Family for their tragic loss.

His Majesty has been our inspiration of love and hope for the past 70 years, and we wish him a most peaceful journey into the next realm.

With his passing, the Thai Nation mourns, in a thousand different ways, with every person from the youngest to the oldest renewing their pledge of loyalty and devotion to the beloved King, and to the entire Royal Family.

The following pages contain part 2 of sometimes repeated, oft quoted excerpts of the incredible life of our most gracious Father of the Thai Kingdom, written by our special correspondent Peter Cummins.

Development for the People

HM King Bhumibol Adulyadej established several Royal Development Study Centres – or, as they are better known – “Living Museums” – situated in the roughest terrain in their respective regions. These centres are the locale for experiments in reforestation, irrigation, land development and farm technology which are conducted to find practical applications within the constraints of local conditions, geography and topography. His Majesty’s aim was to restore the natural balance, to enable people to become self-supporting.

The first centre organized was that of Khao Hin Son, in the rocky area of Chachoengsao’s Phanom Sarakam District. Here, the centre studies how to turn the barren soil, caused by deforestation, back into fertile land again.

Other centres are located at strategic places around the Kingdom.

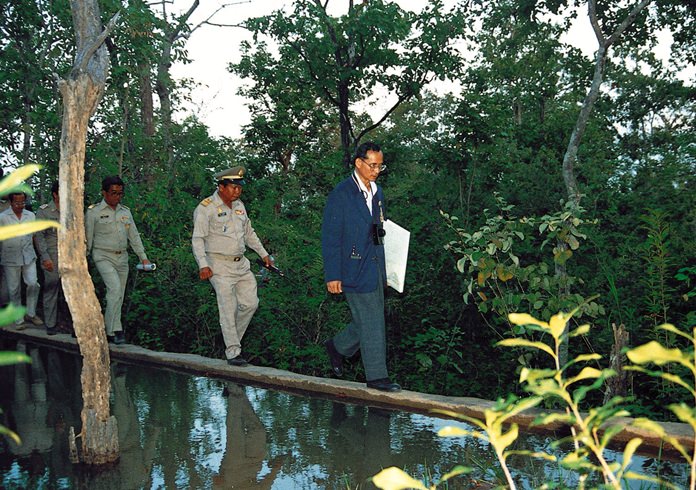

The Pikul Thong Centre at Narathiwat studies the swampy, acidic land of the southern-most region. The Phu Phan Centre in Sakon Nakhon studies soil salinity and irrigation in the country’s biggest region, the Northeast, which suffers from endemic drought. The Krung Kraben Bay Centre in Chantaburi examines the rehabilitation of mangrove forests and coastal areas following massive destruction. The Huay Sai Centre in Petchaburi studies the rehabilitation of degraded forests and shows villagers, in their turn, how to protect the forests.

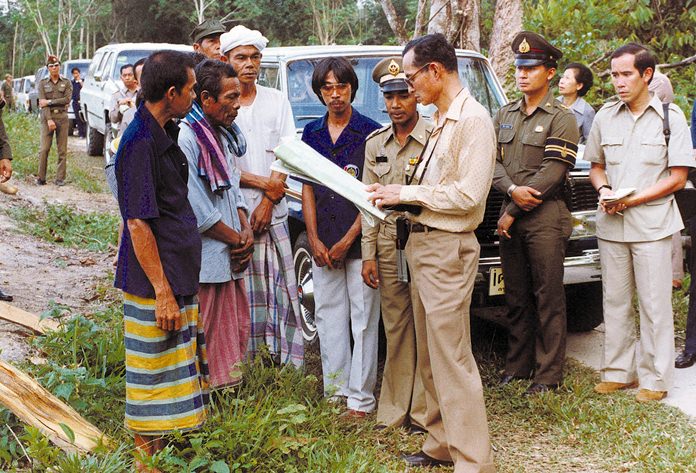

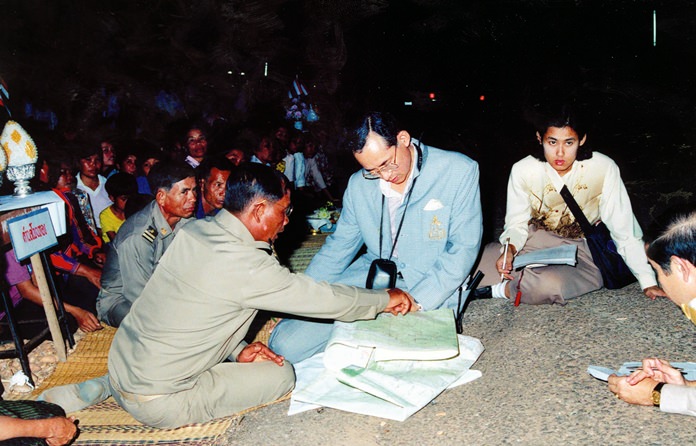

When he was in doubt, HM the King would fly over a particular area, armed with aerial photographs and maps of the terrain, noting features as they passed underneath. And, as he was a good photographer, he also took His own pictures, later to juxtapose them on area charts to obtain a complete and detailed image of the specifics which helped his planning of various development projects.

His Majesty’s insightful approach to local prevailing conditions enabled him to improvise new theories for agricultural development, to provide guidelines for educating farmers on self-sufficiency, and to solve problems of goitre by feeding iodine into salt roads at strategic points.

During all these works, His Majesty promoted a simple approach using environmentally friendly techniques and utilizing moderate amounts of locally available resources. For example, before environmentalism became a major force in the development equation, His Majesty was using vetiver grass to prevent erosion, controlling ground water level to reduce soil acidity, and seeding clouds with simple materials such as dry ice, to produce rain.

A ‘Simple’ approach

The King’s philosophy to development problems was to “keep it simple” – relying on an intimate knowledge of Nature and her immutable law, such as using fresh water to flush out polluted water or dilute it through utilization of normal tidal fluctuations. The ubiquitous water hyacinth too can be ‘harnessed’ to absorb pollutants.

The results of any development, the King asserted, must reach the people directly as a means of overcoming immediate problems, translating into “enough to live, enough to eat”, while looking at a longer-term result of “living well and eating well.”

His Majesty compared this to using adharma (evil) to fight evil, observing that both pollution and the water weed are a menace, but they can be used to counteract each other, thus lessening the damage to the environment.

The King himself practiced this ‘simple approach’ and brought a down-to-earth approach to which the people could readily relate. He studied and deliberated exhaustively on the particular project and then revealed his thinking in short, easy-to-grasp titles. The very simplicity belies the profundity of the philosophy, for each title reflects a much deeper insight into a given problem and often, at the same time, hints at the mode of operation to be employed.

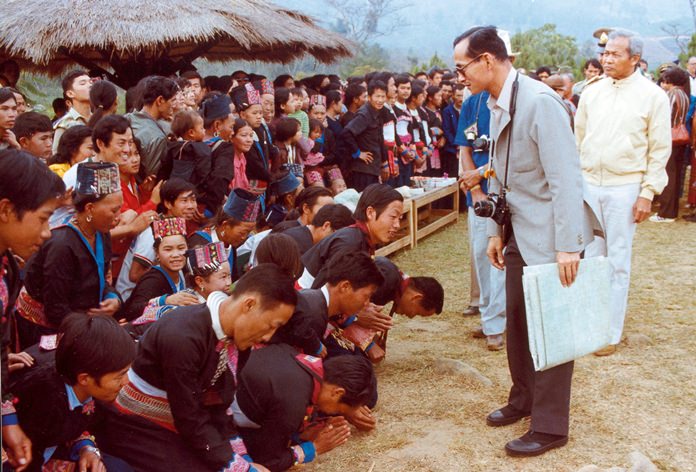

The King undertook the establishment of the Royal Development Projects in 1969, primarily as a means of arresting the opium growing and deforestation caused by the Hilltribes’ slash and burn agriculture and to improve their standard of living. The first was established at a Hmong village on Doi Pui in Chiang Mai Province and now has spread to Chiang Rai, Lamphun and Mae Hong Son. Over the years, the Projects have been instrumental in the conversion of the poppy fields being turned into groves of temperate fruits and vegetables.

Under the dynamic direction of the King’s close colleague, Prince Bhisadej Rajani, who was the Director of the Projects, operating from his base at Chiang Mai University, there are four research stations and 35 Royal Project Development Centres which incorporate some 300 villages, comprising 14,000 households and approximately 90,000 farmers.

The Royal Development Projects Board, under the Office of the Prime Minister, also serves as the secretariat for the Chai Pattana Foundation which is directly responsible for the work related to the royal development projects. Now, many decades later, the results can be seen in the new life which has come to many of the mountain villages. Greenery has returned to once-denuded forest areas and barren hills and the opium cultivation, a cause of extreme national concern, is virtually a past era.

“The key to the success of the Project lies in His Majesty’s guidelines,” explained Prince Bhisadej. “They focus on obtaining knowledge, through research, avoiding bureaucratic entanglements and swift action to respond to the villagers’ needs, while promoting self-reliance,” he added. “The effectiveness of this approach has been applauded internationally.” For example, in 1998 the Royal Project won both the Magsaysay Award for International Understanding and the Thai Expo Award for attaining the quality standard of Thai Goods for Export.

HM the King’s own views were that development must respect different regions, geography and peoples’ way of life. “We cannot impose our ideas on the people – only suggest. We must meet them, ascertain their needs and then propose what can be done to meet their expectations,” HM the King pointed out.

The King’s ideas were in direct contrast to the bureaucracy’s wish to impose standards from the top down, with the inflexibility inherent therein. “Don’t be glued to the textbook,” he admonished developers “who,” he said, “must compromise and come to terms with the natural and social environment of the community.”

The King saw no need to spare any sensitivities – if there were any – because he felt that the government approach is costly and authoritarian which is why it has “failed miserably to address the country’s problems.”

Epilogue

Thus, through the illustrious decades of his rule, HM the King was the very embodiment of his Oath of Accession that, “We will reign with Righteousness for the Benefit and Happiness of the Siamese People.”

The world’s longest-reigning Monarch was “the light of his land, the pride of his people and a shining example to all peoples of a troubled world.”