Perhaps the best horror movie of all time, director James Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) epitomizes the mad scientist in movie history. When Dr Praetorius (Ernest Thesiger) proposes to Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) that they establish a partnership to bring the dead back to life and create a female mate for the Frankenstein monster, it all sounds pretty horrific. In fact the film is a sly and subversive work that smuggled shocking material past the censors by disguising it in the trappings of horror.

Whale’s masterpiece was mostly misunderstood in the 1930s, but today’s audiences are much more alert to the buried hints of homosexuality, necrophilia and sacrilege. Most of these themes center around Dr Praetorius who, as a sideline, keeps tiny humans in sealed bottles, camps it up at every opportunity and shows an unhealthy interest in corpses. The movie, of course, is a sequel to the 1931 Frankenstein in which the monster (Boris Karloff) just about survives being burned in a mill and staggers forth into the world to be misunderstood all over again.

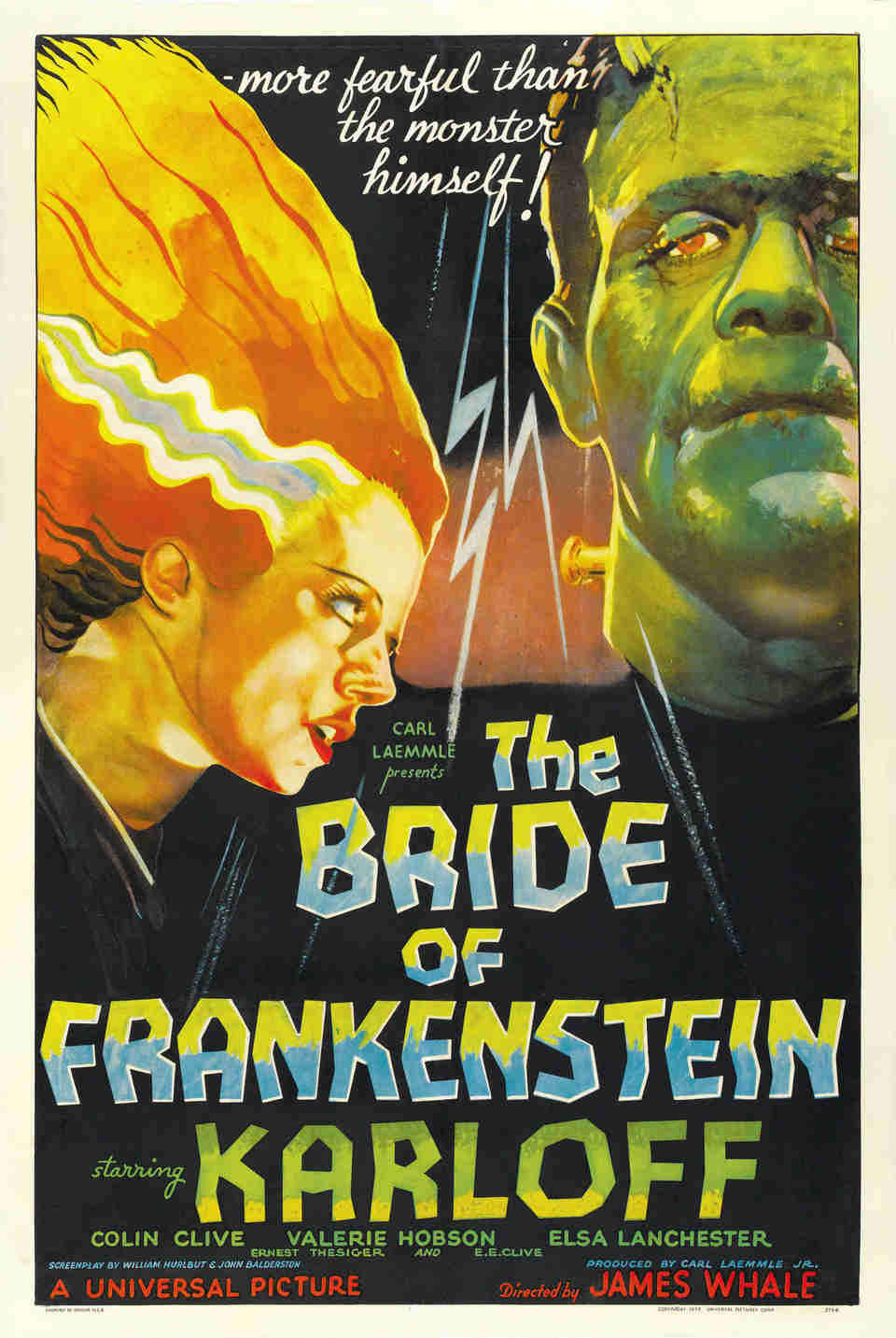

Elsa Lanchester plays author Mary Shelley, who appears briefly in the introduction, but also has the unbilled role of the Bride. She provides one of the immortal images of the cinema with lightning-like streaks of silver hair in a weird hairstyle. Whale based his inspiration for the Bride on a character from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) from where he also borrowed the platform lifting Bride to the heavens accompanied by bolts of lightning. A later movie Young Frankenstein (1975) used the same props which Mel Brooks discovered in Hollywood storage.

The star, of course, is the Monster played again by Karloff with aplomb. Actually his name is not Frankenstein, but it scarcely matters. Unlike the 1931 version where the Monster had no speech, Bride allows Karloff to learn the words “Wine good, fire no good” from a blind violin-playing hermit and later to tell Praetorius that he wants “Friend like me”. The famous scene in which the Monster dines with the hermit (O.P.Heggie) is touching as the latter thanks God for sending him a visitor to break his loneliness. In a later scene with Dr Praetorius, the Monster sits down to a candlelit dinner over a coffin and Karloff puffs contentedly on a cigar. Later generations would call this black comedy.

The Bride of Frankenstein is mostly about Praetorius and the Monster, but there is a sub-plot involving Dr Frankenstein has to postpone his wedding date because of distractions in the laboratory. The climax comes in the celebrated Gothic tower with the bizarre apparatus t o use thunder and lightning to animate the cobbled-together body parts of the intended female marriage partner. Actually the Bride herself appears for only several minutes at the conclusion of the movie, but the impression is unforgettable. Elsa Lanchester’s ability to hiss like a swan in place of human speech sealed her reputation for ever in movie history.

Humor is a large part of Bride, perhaps its most obvious legacy. Frankenstein’s housekeeper Minnie (Una O’Connor) has a scream which would break glass. Then there’s the moment when Karloff saves the shepherdess who has fallen into the water and muses, “Yes a woman. Now that’s real interesting.” One advantage of horror films is that the actors can crank it up with bizarre mannerisms and elaborate posturings which would be quite unsuitable in ordinary movies. Later horror actors Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and Vincent Price all cashed in on this truism.

The horror genre also encourages visual experimentation. Starting with The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919), horror has been the cue for unexpected camera angles and light and dark shadows which later became the hallmark of film noire. Not to mention the hallucinatory architecture and artificial sets which dominate not only Bride but many horror pictures in all generations. Boris Karloff appeared in only one more full-length Frankenstein movie, Son of Frankenstein (1939) before the subject matter degenerated into slapstick comedy with Abbot and Costello. Not until the 1950s did serious Frankenstein movies appear under the auspices of Hammer. Since then, there has never been a pause.

Director James Whale (1889-1957) had a fairly short career as a director, but many biographical details can be glimpsed in the 1998 movie Gods and Monsters starring Ian McKellen. Whale, who was openly gay at a time when few dared to come out publicly, had an early romance with a friend killed in world war one and had several Hollywood greats to his credit. Not only the first two Frankensteins, but The Old Dark House and The Invisible Man. He stopped movie-making in 1941 and lived a quiet life devoted to painting and socializing. He committed suicide by drowning after a series of strokes left him in great pain.