On the surface perhaps, music and painting would seem to have quite a lot in common. They’re both forms of creative expression that can evoke feelings and emotions. Both can transcend language barriers and connect with people from all walks of life. They both can inspire, uplift and move us in profound ways. Both music and the visual arts were influenced by the ideas that brought about the Renaissance and the Baroque. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both music and the visual arts have been influenced by movements like impressionism, abstractism and minimalism.

But delve a little deeper and some important differences emerge. For one thing, music and painting appeal to different senses: a painting exists in a physical space, music exists in time. You could for example, give a painting a quick glance and get the gist of it, recognizing the subject matter, the style, the visual composition and so on. You might even hazard a guess as to who painted it. The more the painting interests you, the longer you’ll probably want to look at it.

You can’t do this with music. Of course, you might spot a few clues about the origin of the music within a few seconds and you might be able to identify the composer. But if the piece lasts half an hour, you’ll need to invest half an hour of your time to hear what it’s all about. Except for recordings, you can’t do a “fast-forward” and select a few audio samples. We could go into more philosophical detail at this point, but that might take us too far off the point.

One thing seems certain though: the arts can inspire each other and visual arts can inspire the creation of music. The concept probably appeared sometime during the late nineteenth century. In 1874, the Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky wrote a suite of piano pieces entitled Pictures at an Exhibition. It was to become a showpiece for virtuoso pianists and it took its inspiration from a selection of drawings and watercolours by the composer’s friend, the well-known Russian architect and painter, Viktor Hartmann, who had died the previous year. The work has become more well known in Ravel’s 1922 orchestral adaption. William Hogarth’s picture, A Rake’s Progress inspired a short opera by Stravinsky of the same name, and some of William Blake’s paintings were the starting point for the 1931 ballet music Job by Ralph Vaughan Williams. When the composer Gian Carlo Menotti was commissioned to write an opera for NBC television, he found inspiration from a picture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Adoration of the Magi by Hieronymus Bosch. The result was the much-loved children’s opera, Amahl and the Night Visitors.

The process can work in reverse. The American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler was so impressed by Frédéric Chopin’s Nocturnes that he created a collection of paintings depicting moody night-time scenes. The Russian artist Vassily Kandinsky’s work was influenced by his synesthesia, a neurological condition in which one sense triggers another. In Kandinsky’s case, he saw colours when he listened to music and used this experience to create extraordinary paintings that he sometimes named after musical terms.

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936): Trittico Botticelliano (Botticelli Triptych). West German Radio Symphony Orchestra cond. Cristian Măcelaru (Duration: 20:20; Video: 1080p HD)

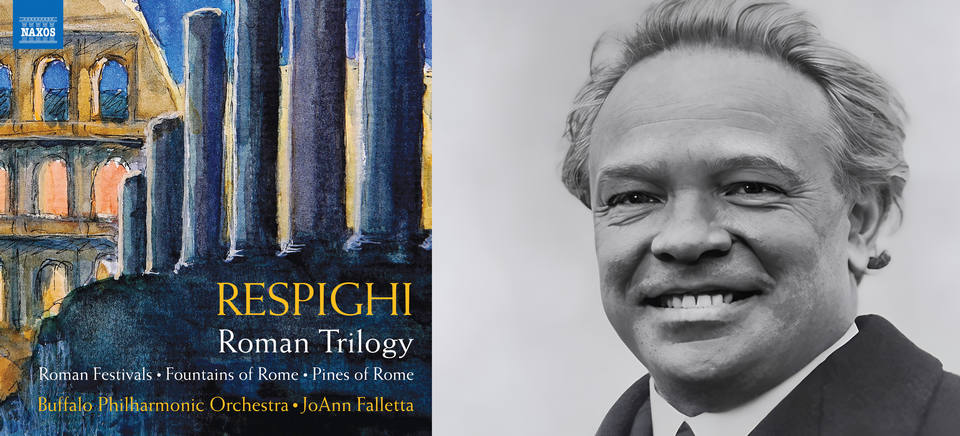

Ottorino Respighi was an Italian composer, violinist and musicologist. He’s best known for his three orchestral tone poems: Fountains of Rome, Pines of Rome, and Roman Festivals. Often known as The Roman Trilogy, they’re fascinating dramatic works which are brilliantly orchestrated with an abundance of infectious melody and captivating imagery. Respighi was born into a musical family and not surprisingly, encouraged to pursue a musical career. Oddly enough, his early studies in music were something of a hit-and-miss affair but despite the shaky start, Respighi eventually became one of the leading Italian composers of the 20th century. Even so, I think his highly personal musical style deserves much more attention. We simply don’t hear enough of Respighi.

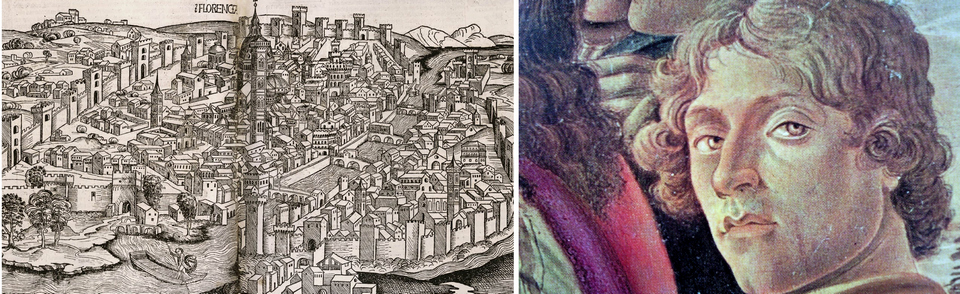

One of his lesser-known works is the Trittico Botticelliano (“Botticelli Triptych”) which is also known as Three Botticelli Pictures. Completed in 1927, the work is scored for small orchestra consisting of flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trumpet, glockenspiel, triangle, harp, piano, celesta and strings. Each of the three movements is a musical interpretation of three paintings by Botticelli, which at the time were on display at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. They still are.

Botticelli, as you may recall, was one of the greatest humanist painters of the early Renaissance. He was born in Florence in 1445 and important not only because he was a brilliantly talented painter, but also because he was one of the first Western artists to depict non-religious subjects. The idea that art could be created for pleasure, and not merely serve religious purposes, was something of a breakthrough at the time. During his long career, Botticelli’s work revealed an emerging knowledge of human anatomy and perspective with an emphasis on beauty and detail. His paintings often show social interaction between ordinary people. Influenced by the revival of Greek and Roman ideas, the goddess Venus is the subject of many of his most famous works.

The first movement of Respighi’s Trittico Botticelliano is entitled La Primavera (Spring). It is a musical depiction of Botticelli’s painting of the same name completed sometime around 1480. The painting has been described as “one of the most controversial paintings in the world”, perhaps because it is so enigmatic and can be interpreted in different ways. The painting depicts a group of people from Greek classical mythology in a garden full of fruit trees. Centre-stage is a dreamy-looking Venus, who stands beneath a floating and blindfolded Cupid, armed with his traditional bow and arrow. The west wind, Zephyr is depicted by the grey, shadowy figure at the extreme right who appears to have an unhealthy interest in the nearby nymph Chloris.

The blindfolded Cupid is taking aim at the unsuspecting Three Graces, the three youthful goddesses who embody all things beautiful, joyful and abundant. At the extreme left is the scantily-clad Mercury with his (barely visible) winged sandals, apparently attempting to dislodge a ripe fruit with his trident. Although it is not entirely obvious what is going on, this is a wonderful picture, full of humour, movement and activity, and Respighi reflects this in the busy opening movement with its exuberant evocation of spring. Woodwind and upper strings play sparkling trills while the horns and other instruments play a repeated short fanfare-like figure a though announcing the coming of spring. The bassoon introduces a renaissance-sounding dance tune, which is later played by the full ensemble. The orchestration is brilliant, light and transparent; the music full of joie de vivre and with sumptuous harmonies. It’s segmented, almost like a series of colour photographs. The movement ends with quiet trills from the violins, suggesting perhaps a light spring breeze rippling through the fruit trees.

The second movement (06:02) derives from Botticelli’s 1474 painting Adoration of the Magi which refers to the arrival of the Magi who have come to visit the new-born Jesus. This was a favourite theme among European painters and Botticelli was commissioned to paint the scene at least seven times. In the Biblical nativity story, the Magi are also known as The Three Wise Men or The Three Kings and first mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew. Their identity and origin are shrouded in mystery. Some Biblical scholars believe that the Magi (a Greek word) may have been members of a priestly caste rather than kings, revered for their knowledge of astrology and the magical arts which at the time were intertwined with religion, science and astrology.

In the painting, Botticelli replaced the Magi with deceased members of the Medici family, presumably at the request of Gaspare di Zanobi del Lama who commissioned the work. Many of the other people in the picture are chatting with each other, others are just looking on passively. Three of the subjects seem to be gazing out at the viewer. One of them is Botticelli himself, who like the film director Alfred Hitchcock did five hundred years later, added himself as one of the “extras”. He is the man wearing the modest yellow cloak at the far right of the picture.

Respighi’s musical version of the scene opens in a meditative mood with a lilting bassoon solo, later to be joined by oboe. Later we hear from the woodwind, the medieval hymn Veni, Veni Emanuel (“Oh Come, Oh Come Emanuel”) and the Italian Christmas song Tu scendi dalle stelle (“You descend from the stars”) eventually taken up by the strings and magically transformed into new musical ideas. Sometimes the music sounds distinctly Oriental, for the Maji were supposed to have come from the East. The music wends its way slowly through different moods and keys (at one point arriving in the unusual key of G flat) and creating an evocative and pastoral sense of wonder and mystery.

The third and last movement (14:45) is inspired by the painting La nascita di Venere (“The Birth of Venus”), one of Botticelli’s most famous and recognizable works. The picture shows a fully-grown and somewhat wistful Venus floating to the shore and standing, slightly uncomfortably on a gigantic scallop shell. On the left, Zephyr, the west wind, blows her ashore and carries in his arms Aura, the lighter wind. To the right of the picture, a levitating woman holds out a heavy dress for Venus to wear. She is one of the three Horae, the Greek minor goddesses who attend to the needs of Venus.

The music, like the forms in the painting is beautifully shaped with delicate lines. The flute plays an Arabic-sounding melody and gradually we can feel an underlying sense of slow, organic growth in the music as new melodic lines emerge from the glistening textures. The music suggests the movement of the water and the gradual increase of tension and loudness perhaps suggest the growth and the rising of the god Venus. It reaches a musical climax and then, suddenly, silence. The music retreats almost to nothing. The piece ends with the gentle undulations of the waves slowly receding as the goddess departs. It’s a musical gem.