I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not much good at dancing. Not much good at all. To be more precise, I am completely useless. I’d have a better chance of parsing Sanskrit than doing a tango. When I was a student at high school, we used to have Christmas Social Evenings in which there would be dancing, games and other enforced forms of merriment. I used to dread them, especially the dancing. In the weeks before the event, physical education lessons would be replaced by dancing lessons in which we were all obliged to learn dances such as The Valeta and the Boston Two-Step, both of which date from the 1900s and were considered hopelessly old-fashioned by us teenagers of the Fabulous Fifties.

Incidentally, I borrowed the rather enigmatic expression The Dance of Life from the title of an early sound film made in 1929, which was an adaptation of a popular play exploring the personal struggles and ambitions of a group of vaudeville performers. Strangely enough, nobody knows exactly when people started to dance even though dance seems to be present in every culture across the world. It was probably a natural expression of joy or elation or perhaps even – in its early days – frenetic bodily motions to frighten away undesirable animals. The earliest historical records of dance are cave paintings in India which date from about 8,000 BCE and Egyptian tomb paintings which depict dancing activities in about 3300 BCE. Although dance for ceremonial or religious purposes might have existed without musical accompaniment, it’s difficult to imagine dance without music. For the last couple of millennia music and dance have become inextricably intertwined.

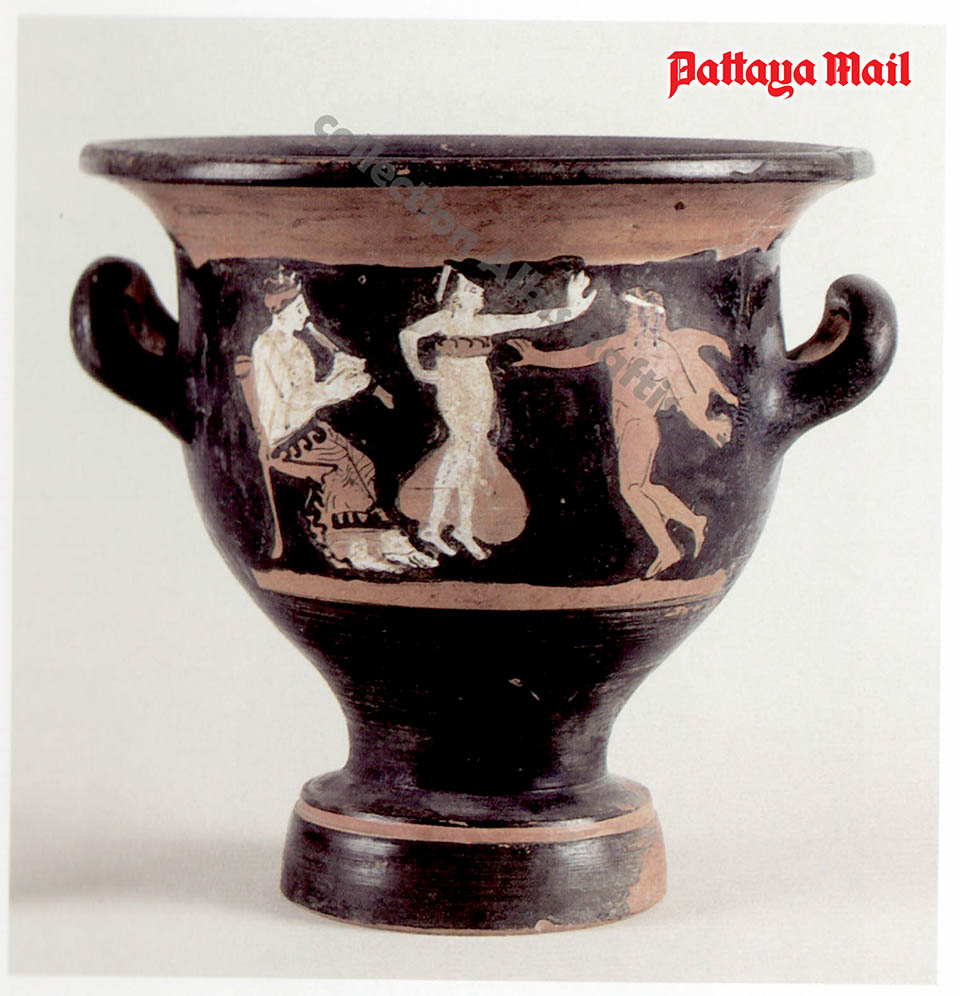

Formalized dancing was practised among the ancient Greeks and was an important part of everyday life. Many household objects such as drinking vessels depicted images of dancers and musicians. Dance was incorporated into celebrations of the wine god Dionysus (and later the Roman god Bacchus) and into ritual dances at the ancient Greek Olympic Games. The Greeks took dance seriously, because dance-training (gymnopaidai) was a foundation subject in school for both boys and girls. Even so, we don’t know an awful lot about what the music sounded like.

Social dancing grew out of folk dances, many of which were simple and repetitive. The folk dances of the European Middle Ages were the starting point for formal ballroom dancing of centuries later. The royal courts took dancing to heart and it was there that the earliest forms of ballet emerged. By the 18th century, ballet has become an art. When it developed in the 17th century during the reign of Louis XIV, ballet became more than just a noble entertainment. It was a major art and an exercise in aristocratic education.

The Renaissance saw an increasing amount of dance music being published. The invention of the printing press opened the doors to music publishing and enormous collections of dance music were produced during the second half of the sixteenth century onwards. The most notable and prolific composers and arrangers were Michael Praetorius, Tielman Susato and publisher Pierre Phalèse who started a bookselling business in the town of Leuven. By 1575, Phalèse had produced nearly two hundred books of popular dance music, many of which were for the lute, a popular instrument at the time. At first, Phalèse outsourced his publications to various printers, but later produced his own using the state-of-the-art technology: movable type. To be fair, the technology wasn’t all that new, because the first movable type printing technology was developed in China during the 11th century.

The dance suite, intended for listening rather than dancing, emerged in the late fourteenth century and consisted of four of five dance melodies strung together, sometimes with an opening prelude. During the baroque, the dance suite became tremendously popular. Much of the music took the form of stylized dances usually in the form of instrumental suites. They consisted of dances such as the allemande, courante, sarabande and gigue and also intended for listening and courtly entertainment. Many composers contributed to the genre, notably Bach, Handel, and Telemann. During the eighteenth century, the dance suite fell temporarily out of favour but was revived again in the late nineteenth century, sometimes as a collection of dances from a ballet. Many composers have been attracted to ballet, an art-form that brings together the concepts of bodily action in space and time and usually with an underlying narrative.

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967): Dances of Galánta. London Philharmonic Orchestra, cond. Vladimir Jurowski (Duration: 15:23; Video: 720p HD)

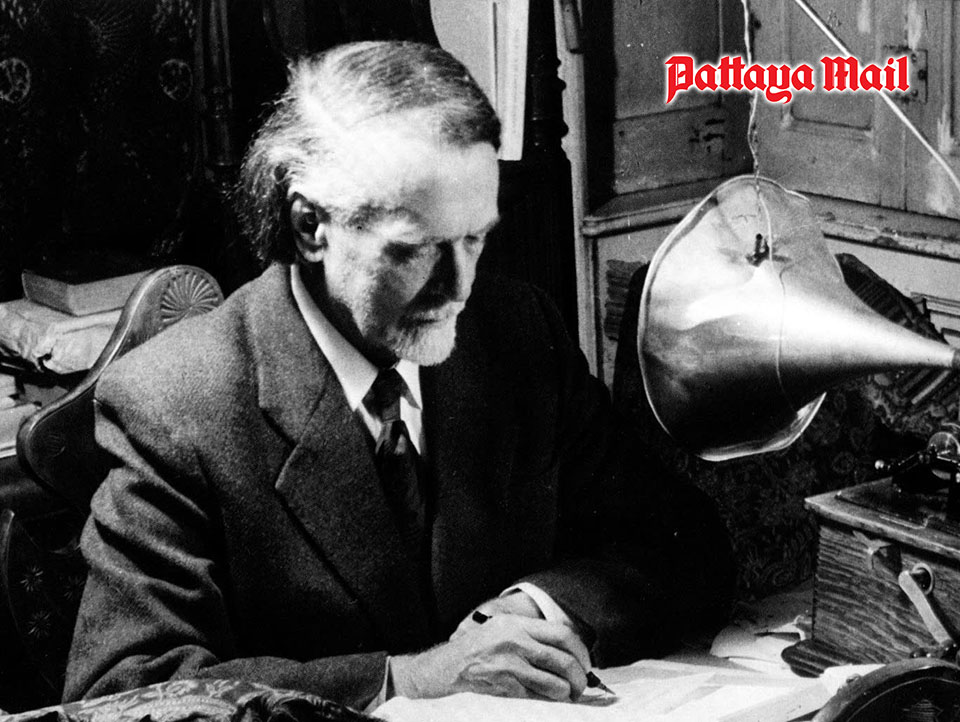

Kodály had a passion for folk music and in his early twenties, he visited remote Hungarian villages to collect songs. When audio recording eventually became possible, he recorded many folksongs on phonograph cylinders for later transcription into musical notation. He eventually met fellow-composer and compatriot Béla Bartók. The two became lifelong friends and champions of each other’s music. In 1959, Kodály caused a stir in social circles when the 77-year-old composer famously married one of his 19-year-old students from the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. My mother, who held upright moral values, was shocked.

Zoltán Kodály (zohl-TAHN koh-DAH-yee) is best-known as the creator of the so-called Kodály Method of music education. He became interested in children’s music education in 1925 when he happened to hear some school children singing in the street. He was horrified by their tuneless squawking and assumed that music teaching in the schools was to blame. He set about a campaign for better teachers, a better curriculum and more class-time devoted to music, especially singing. His tireless work resulted in many publications which later influenced music education world-wide.

Kodály is most closely associated with a teaching aid he didn’t invent: the hand-signs. These hand-signs represent each note of the scale and were invented by the English minister and music teacher John Curwen in the mid-nineteenth century. Curwen also invented the Tonic sol-fa system of music education and the hand-signs were a natural extension of this. The hand-signs were used in Steven Spielberg’s 1977 movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but they were hardly necessary and were perhaps included to add a bit of gravitas to a rather implausible scene.

Kodály wrote his colourful and sparkling Dances of Galánta in 1933 using folk music of the Galánta region, now part of Slovakia. The work is in five sections and brilliantly orchestrated with the clarinet taking a prominent role, because it represents the traditional Hungarian tárogató, a single reed instrument whose conical bore produces a unique and slightly raucous sound, somewhere between that of an oboe and a soprano saxophone.

Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983): Dance Suite from “Estancia”. Frankfurt Radio Symphony cond. Andrés Orozco-Estrada, (Duration: 13.37; Video: 720p)

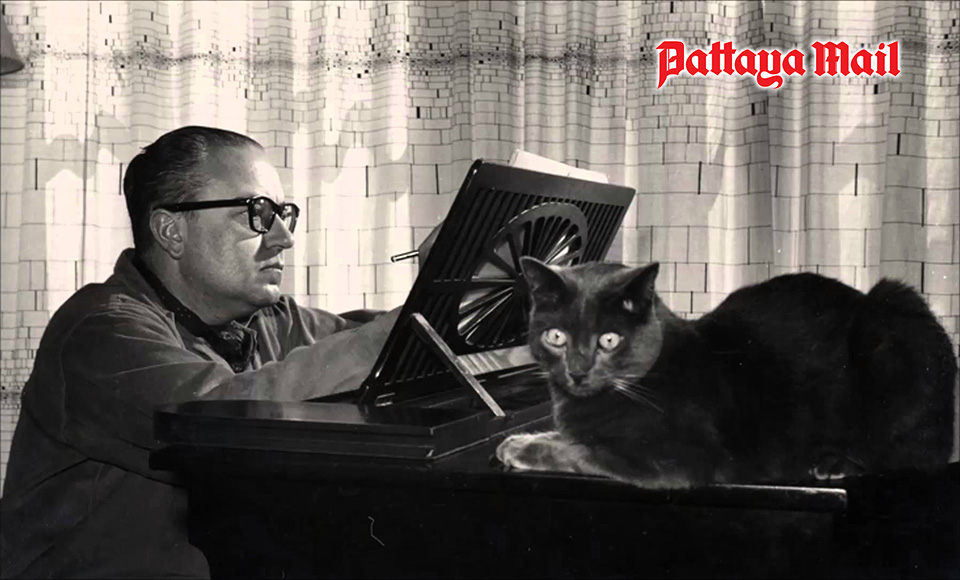

Now here’s something that really deserves to be better known: thrilling music from the composer Alberto Ginastera who was one of the most powerful voices in Argentine orchestral music. Ginastera (jee-nah-STEHR-ah) studied at the conservatoire in Buenos Aires, and later with the American composer Aaron Copland. Ginastera’s music can be challenging, percussive, thrilling, thought-provoking and sometimes even downright scary. The thunderous last movement of the dramatic First Piano Concerto was brought to fame in 1973 when it was adapted by the rock group Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Ginastera even approved of the arrangement, which relied heavily on keyboards and synthesized percussion.

Much of Ginastera’s music is nationalistic and draws on Argentine folk themes or other elements of traditional music. He greatly admired the traditions of the Gaucho, Argentina’s answer to the American cowboy. They were (and still are) celebrated for their solitary and nomadic lifestyles, superb horsemanship, elaborate attire and a culture deeply rooted in the country’s history.

The Gaucho culture forms the background to Ginastera’s 1942 one-act ballet Estancia (“The Ranch”). It’s a story about a city boy who falls for a rancher’s daughter, but the girl finds him weak and colourless compared to the macho and intrepid Gauchos.

Ginastera turned the ballet music into an exciting four-movement orchestral suite and if you haven’t heard Ginastera’s compelling music before, this is a great place to start. All the hallmarks of his style are there: his love of percussive sounds, his sparkling angular melodies and his tremendous sense of rhythm.

You would need a heart of stone to not be moved by the dazzling last movement Danza final (Malambo) (at 09:16) which is an absolute “must hear”. The closing section is thrilling, with relentless, cataclysmic percussion and brilliantly articulated playing. This fine German orchestra is superb and the musically-gifted and energetic conductor Andrés Orozco-Estrada clearly enjoys every moment of this action-packed music.