Throughout the course of human history, there have always been a few individuals who have undertaken tasks, often at considerable personal risk, for the benefit of others. They were not necessarily well-known, but they chose to go against the flow and do what seemed the most appropriate thing at the time. One such individual was Karl-Albert Brüll who, during the early 1940s was an officer at the German prisoner-of-war camp known as Stalag VIII-A at Görlitz in Silesia. Before the war, he had been a lawyer who enjoyed music. At Stalag VIII-A, he became an unsung hero who secretly opposed the monolithic Nazi thinking and went out of his way to protect the imprisoned Jews at the camp. He advised them not to escape, arguing that their life in Germany or German-occupied France would be more dangerous than life inside the camp. And if it had not been for officer Karl-Albert Brüll, Messiaen’s iconic and far-reaching work Quatuor pour la fin du Temps may never have been written.

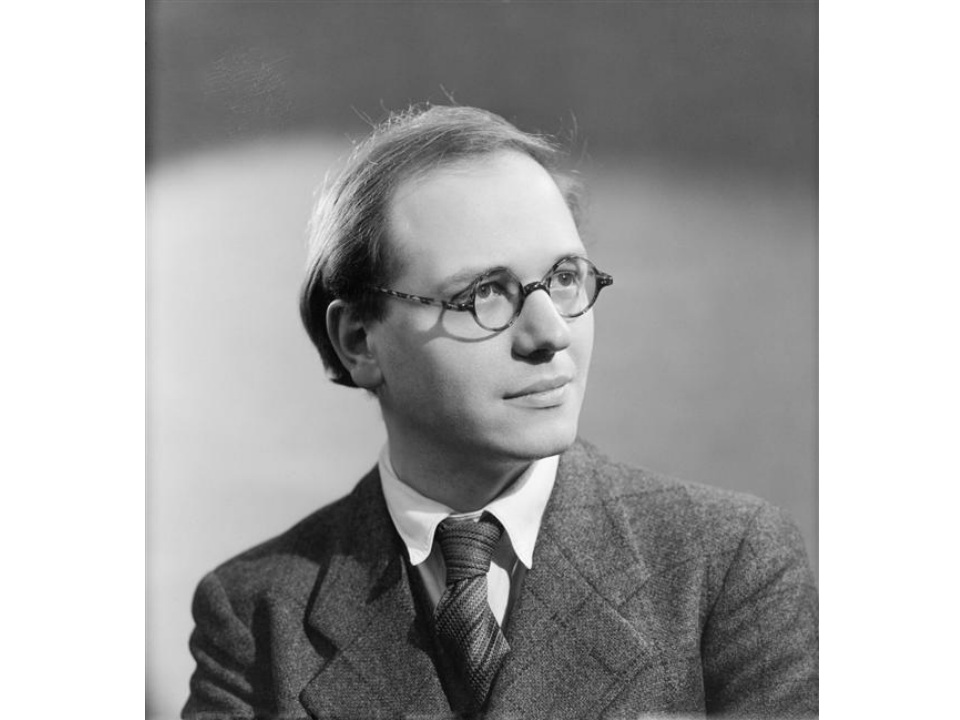

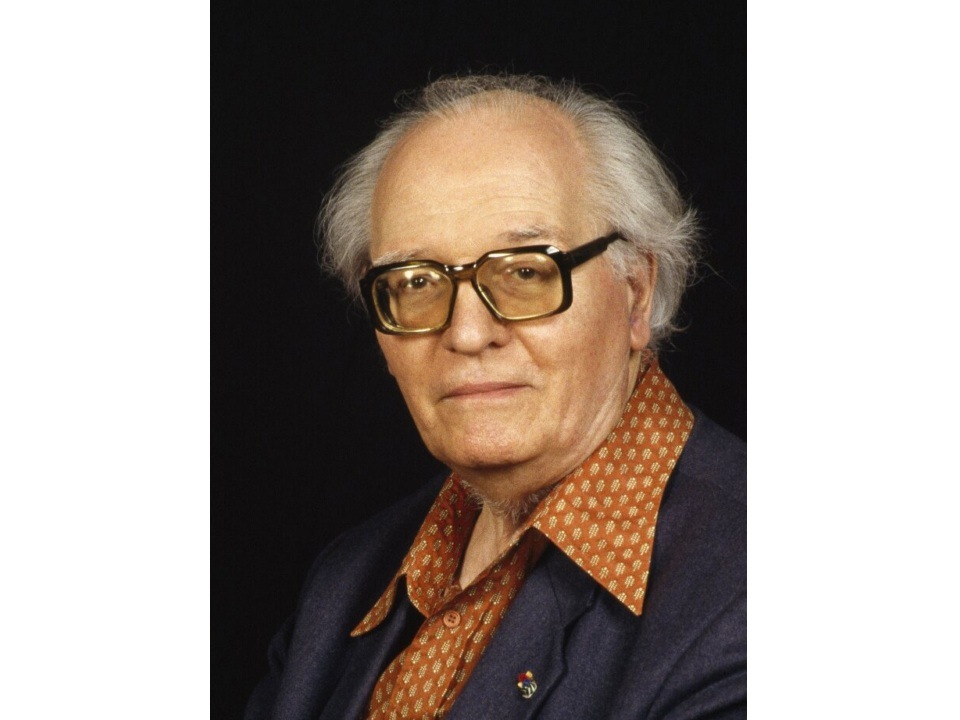

Olivier Messiaen was one of the most significant composers of the twentieth century. He was also an organist with a passionate interest in ornithology. He wrote a vast amount of music and during the 1930s, taught at the renowned Ecole Normale de Musique in Paris. Messiaen was also organist at the Église de la Sainte-Trinité, a post he held for 61 years. In 1939, at the beginning of what was to become World War II, the 31-year-old composer was drafted into the French army. Because of his poor eyesight, he was enlisted as a medical auxiliary rather than an active soldier.

After the fall of France in 1940, Messiaen was captured in Verdun where he’d been working as a hospital nurse. With the other prisoners, he was transported to the German prisoner-of-war camp known as Stalag VIII-A at Görlitz in Silesia, now close to the Polish border. He was imprisoned for nine months and conditions in the camp were harsh. Nearly 50,000 French and Belgian prisoners were huddled into three barracks built to hold 500 prisoners each. Prisoners were under-fed and unprotected from the brutally cold winter weather.

“When I arrived at the camp, I was stripped of all my clothes, like all the prisoners,” Messiaen said. “But…I clung fiercely to a little bag of miniature scores that served as consolation when I suffered. The Germans considered me to be completely harmless, and since they still loved music, not only did they allow me to keep my scores, but an officer also gave me pencils, erasers, and some music paper.” The officer to whom Messiaen referred was of course Karl-Albert Brüll who was evidently excited by the presence of a well-known composer. He provided not only manuscript paper, but also extra food and even posted a guard at the door of an isolated barracks to enable Messiaen to work in privacy. Messiaen was excused from routine chores and assigned an early-morning watch, to accommodate his interest in ornithology.

Thanks to Karl-Albert Brüll, Messiaen was able to write Quatuor pour la fin du Temps (“Quartet for the End of Time”), described by music historians as one of the most important works of the twentieth century. It is scored for the unusual combination of violin, cello, clarinet and piano: the only instrumental players who happened to be imprisoned at the camp. The piece was written over the course of several months and was rehearsed each day as sections were completed.

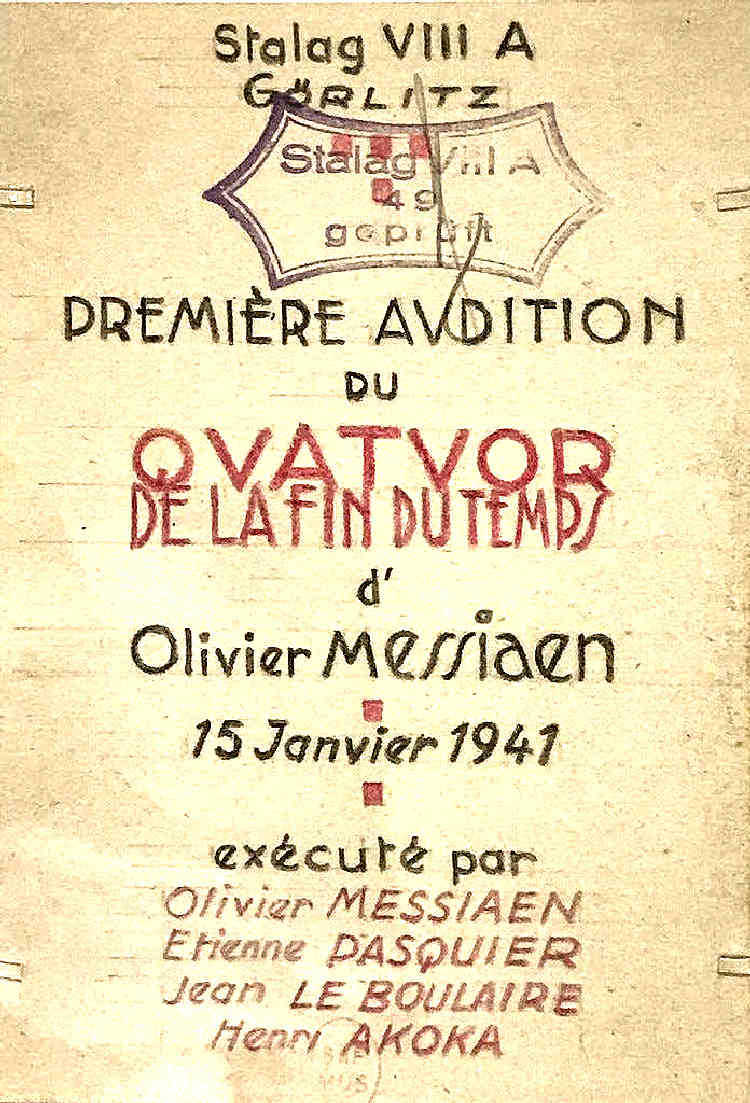

The quartet was first performed in a prison hut – Barrack 27 – at Stalag VIII-A on the evening of 15th January 1941 to a cramped audience of about four hundred prisoners and a few German officers seated on the front row. Outside the hut, snow covered the ground and the temperature was below zero. For many huddled together in the unheated hut, it was the first time they had heard chamber music of any kind. “Never had I been listened to with so much attention and understanding,” Messiaen recalled. Probably with a considerable degree of perplexity too, for Messiaen’s music is rarely simple. A fellow-inmate at the camp designed the concert program in Art Nouveau style, to which an official German stamp of approval was added. In the following weeks, the courageous officer Karl-Albert Brüll arranged for Messiaen’s return to France and conspired in the forging of the necessary documents.

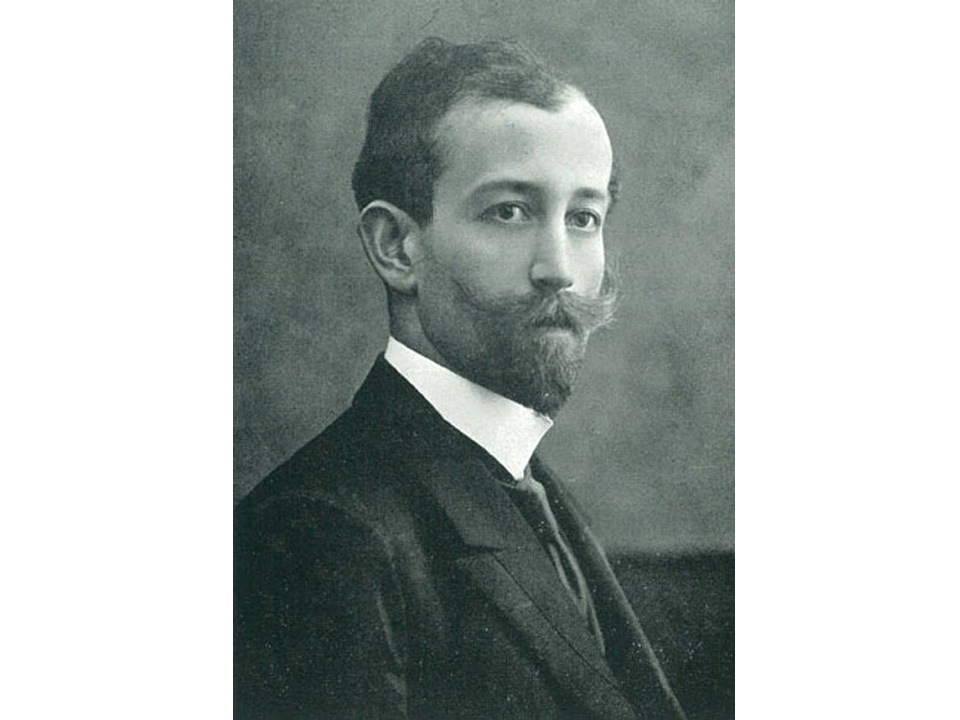

The Quartet for the End of Time has since justifiably become one of Messiaen’s best-known works and was aired once again recently at Ben’s Theater Jomtien at a concert appropriately entitled Echoes from the Abyss. The concert was given by a quartet of established professional musicians: Yada Lee (violin), Sarai Arsa (cello), Sooksan Ratanapol (clarinet) and Eri Nakagawa (piano). They opened the concert with the Quartet for Piano, Violin, Clarinet, and Cello, Op.1 by the slightly obscure Austrian composer Walter Rabl. The opus number reveals that it was the composer’s first publication and it had previously won first prize in 1896 at a prestigious competition for young composers sponsored by the Viennese Musicians’ Society. Johannes Brahms was the Honorary President and a judge of the competition and was also known as a vigorous promoter of competitions to bring young talents to the fore. At the time of the competition, Walter Rabl was completely unknown.

Rudolf Felber writes, “Rabl’s chamber works are influenced by both Schumann and Brahms, but they are fresh and enjoyable compositions of considerable artistic worth.” Even so, with a mere handful of published works, Rabl stopped composing entirely at the age of thirty and devoted himself to conducting and vocal coaching the rest of his life. Perhaps his music seemed just a bit too old-fashioned for the early years of the twentieth century.

At Ben’s Theater, the musicians gave a compelling performance of the Rabl quartet, which is musically conservative but at times is technically demanding. I was especially impressed by the quartet’s sensitive performance of the second movement, the Adagio molto, in which the playing was perfectly balanced with a fine sense of phrasing and “placing” of the notes. There was splendid articulation from pianist Eri Nakagawa and delightfully rich string tone enhanced by the clear liquid clarinet tone of Sooksan Ratanapol. This second movement seemed to me one of the highlights of the evening.

The lilting third movement contained echoes of Johann Strauss II, whose music was all the rage in Vienna at the time. The joyful fourth movement showed the players at their virtuosic best, passionate music yet played with a charming lightness of touch and superb articulation. Eri Nakagawa provided some brilliant piano playing in this movement and the quartet brought it to a triumphant ending. I think Brahms, to whom the work was dedicated. would have enjoyed this enthralling and colourful performance.

Violinist Yada Lee has a distinguished international career as an orchestral musician and a concert violinist. She holds degrees from Mannes School of Music and Oberlin Conservatory and received an Artist Diploma from The Glenn Gould School of The Royal Conservatory. She has appeared as a guest violinist with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and has performed with Symphoniker Hamburg, the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra and the Canadian Opera Company. She made her New York solo debut at Lincoln Center in 2014, performing Prokofiev’s challenging first violin concerto.

Sarai Arsa started playing the cello when he was thirteen and later became a student at the College of Music, Mahidol University where he studied with Marcin Szawelski, a regular performer at Ben’s Theater. In 2019, Sarai played cello solo in the Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations with the Mahidol Symphony Orchestra. He also took part in the inaugural season of the Korean National Symphony Orchestra in Seoul in 2021 and performed on their 2022 European tour at concerts in Hungary, Slovenia and Poland.

Sooksan Ratanapol is currently the Principal Clarinetist of Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra. He studied at Universität für Musik und Darstellende Kunst Graz, Austria and later at the Staatliche Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst in Stuttgart. During his orchestral career, he has performed with many orchestras such as the Stuttgarter Kammerorchester, Junge Oper Stuttgart, the Saigon Philharmonic Orchestra, the Siam Philharmonic and the Bangkok Symphony Orchestra.

Pianist Eri Nakagawa is a native of Osaka, Japan and has been on the Piano Faculty of Mahidol University College of Music since 1995. Before then, she taught at Ball State University, Indiana where she later completed her Master’s and Doctoral degrees. She has been guest pianist and professor at many universities world-wide. Eri has performed at many festivals including the Corfu Festival in Greece and the Sicily International Piano Festival in Catania. At Mahidol University, she has played more than ten concertos with the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra.

The second part of the concert featured the Messiaen quartet which is a challenging work both technically and artistically. The composer had always been fascinated with bird-song and often incorporated birdsong transcriptions into his music. In his preface to the Quartet, he mentions blackbirds and nightingales. However, the single most important driving force of the Quartet was not birds, but Messiaen’s devout Catholic faith. Messiaen explained that the work was inspired by the text from the Book of Revelation, the final book of the New Testament and the expression “the end of time” alludes to the Apocalypse. The quartet is dedicated “to the Angel of the Apocalypse”.

Messiaen’s style of writing makes enormous demands on the players because he avoided regular rhythms and instead wrote ever-changing, unpredictable rhythmic patterns. I first came across this work in the early 1960s and even then, it was considered somewhat avant garde although even as a music student I found the work immensely captivating.

The opening short first movement, Liturgie de cristal gives a foretaste of the music to come. It begins with the clarinet imitating a blackbird’s song, the violin imitating a nightingale’s song followed by bird-like twittering from the clarinet and haunting, shimmering melodic lines from the strings. With the highly chromatic chords on the piano this is a challenge for the musicians, but they played with a sense of confidence and commitment and really seemed to grasp the essence of the music. The dramatic second movement was played with panache and exceptionally good ensemble given the difficulty of the work. The soft chromatic chords were beautifully played by Eri although the piano tended to dominate with the result that the entrancing melody played by the violin and cello was not always audible.

The third movement Abîme des oiseaux is for solo clarinet and was given a superb performance by Sooksan Ratanapol. This eight-minute-long movement contains many blackbird-like moments and although the tempo changes frequently, the music contains no time signatures to assist the player. It ranges in dynamics from almost inaudible to extremely loud – often on the same note. The player is sometimes required to play a high note incredibly softly and this is a challenge in itself. I was greatly impressed with Sooksan’s pure and luminous tone, his expressive performance and his impeccable sense of timing in the long pauses.

The fourth movement Intermède is a musical gem of its own, which starts with the instruments in unison. Written just for strings and clarinet, it’s in duple time throughout and is lighter in character than the other movements. The musicians played with a superb sense of ensemble and were perfectly balanced: a fine example of chamber music playing. I have always found that the fifth movement, Louange à l’éternité de Jésus is one of the most moving movements in the entire work. I would even suggest that it’s one of the most moving pieces ever written. It’s an extremely slow and lyrical piece for cello and piano taking the form of an extended melody; opening in the bright key of E major and drifting through other different keys as the piece unfolds. Cellist Sarai Arsa gave a stunningly beautiful performance of this majestic and captivating music. Messiaen was always very specific about dynamics and in this movement. However, the repeated piano chords were sometimes played too loudly and obscured the cello melody. Sarai has a lovely bright tone quality, especially in the higher range. The final moments of the movement were sublime.

The sixth movement, Danse de la fureur is furious indeed. Surprisingly, all four instruments play in unison throughout and the movement uses enormous contrasts in dynamics, ranging from ppp which is just about audible to ffff which is about as loud as you can get. This wild, terrifying movement features a jagged angular melody which morphs into different forms as the piece progresses. Messiaen himself wrote of this movement, “Music of stone, formidable granite sound; irresistible movement of steel, huge blocks of purple rage…” The four musicians gave a stunning performance of this intensely difficult movement with superb articulation and sense of ensemble.

The penultimate movement Fouillis d’arcs-en-ciel opens with cello and piano and once again gave the audience the opportunity to hear Sarai’s lovely cello tone. The piece contains various passages from the second movement and there is some cleverly written bird-like interplay between violin and clarinet. Again, the musicians performed impeccably with superb precision and complete control of the extended unworldly trilled notes towards the end of the movement.

The magical, hypnotic last movement Louange à l’immortalité de Jésus is incredibly slow, each beat lasting almost two seconds. For me at least, it is one of the highlights of the work. Scored for just violin and piano, the violin weaves a long, seemingly meandering but finely structured melody over an endless progression of hypnotic repeated piano chords. Yada and Eri performed the movement to perfection, though to my ears the piano sometimes seemed too loud. Even so, the two musicians brought out the mystical quality of the music and Yada’s lyrical playing and radiant violin tone matched the ethereal mood. Gradually and almost imperceptibly, the melody climbs higher and higher – to the highest note in the piece, after which it slowly dies away peacefully to silence, to heaven and to eternity.

This final movement reminded me again of Messiaen’s special kind of genius, for while the music can be appreciated at a highly technical level, it can also provide an intensely emotional and moving experience for anyone who gives it time. Perhaps it’s because the sound-world that Messiaen creates is so evocative: it takes us to an unknown country: to a distant shore at the far edges of our imagination.

This was yet another exceptional concert at Ben’s Theater. The four brilliant musicians displayed technical virtuosity and artistic understanding. It was a captivating success.