“Then there is the music: colourful, lush, grand and intimate, vast and deeply personal all at the same time. The composer creates the most incredible musical waves that sweep over you. In the space of seconds his music can reduce you to tears, an emotional assault of the most delicious and cathartic sort… he can create frisson – a sudden physical thrill, like a chill or shiver or tingle of excitement – more easily than any other composer.” So writes the well-known cellist and writer Daniel Lelchuk, but whose music is he describing?

It could only be that of Giacomo Puccini. In his day, Puccini (poo-CHEE-nee) was a musical superstar whose international fame was matched by his colourful lifestyle. He was attracted to speed and the fascination for the modern world which was beginning to emerge. He adored fast cars and fast boats, hunting and fishing; he enjoyed drinking and cooking meals for friends; he chain-smoked cigarettes and high-nicotine Toscano cigars for most of the day and often well into the night. And as well as fast cars, he also enjoyed the company of loose women.

His first car was a 1902 French De Dion-Buton which wasn’t particularly fast and could manage about 25mph on a good day. Despite its clunky looks, it caused admiration and amazement on the local streets, for at the time there were only about nine hundred cars in the whole of Italy. His second car was an ill-fated Clément Bayard which on one disastrous occasion, when being driven by his chauffeur, fell into a ditch on a dirt road and overturned, pinning Puccini underneath. He could have been killed, but escaped with a fractured leg, though it was many months before he fully recovered.

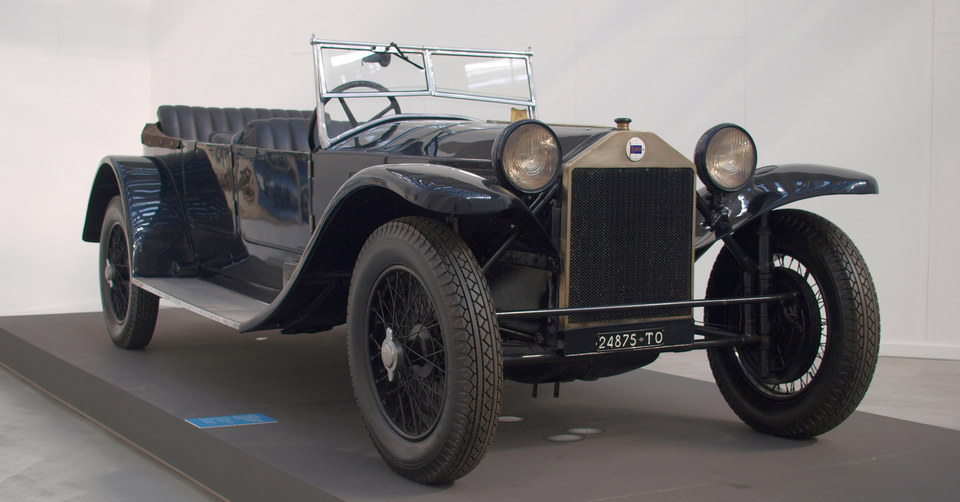

From then on, he acquired a series of sporty cars and his last one was a Lancia Lambda, in which he made his final car journey. He had previously been diagnosed with throat cancer (which was more advanced than he or his wife realised) and his doctors recommended an experimental radiation treatment available at a hospital in Brussels. On 4th November 1924, Puccini went to Pisa station in his Lancia Lambda to catch the train for Brussels. Unfortunately, the radiation treatment probably came too late and the cancer proved fatal. He never returned to Italy, for he died in Brussels at the relatively young age of sixty-five.

Puccini had been born in December 1858 into a family of musicians in the Italian town of Lucca where he was named, somewhat grandly as Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini. The family was established by Puccini’s great-great-grandfather who in the mid-eighteenth century was the maestro di cappella of the Cattedrale di San Martino in Lucca. Thanks largely to hard work and good luck, Puccini eventually became the leading Italian composer of his generation and considered the greatest composer of Italian opera after Verdi.

Puccini was the leading exponent of the genre of opera known as verismo (Italian for “realism”) in which stories from real life were used. Unlike classical opera, the verismo approach focused not on gods, mythological figures or royalty, but on ordinary people and their problems, sometimes of a romantic or passionate nature. Puccini’s best-known operas works include La Bohème (1896), Tosca (1900), Madama Butterfly (1904) and Turandot which was unfinished at the time of his death in 1924, but completed the following year by the Italian pianist and opera composer Franco Alfano. In these works, the music and drama are seamlessly matched and have become the most-performed operas in the repertoire.

The most striking feature of Puccini’s music is his ability to create magic and effortless lyricism in just a few notes, but he was also a master of orchestration. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Puccini produced work relatively slowly, usually about one opera every four or five years. The writing of Madama Butterfly was further slowed down due to the consequences of the car crash in 1903.

Even a hundred years after his death, Puccini’s operas remain so popular that a concert programme of his music is almost certain to sell out. And it did at Ben’s Theater in Jomtien, at a recital given recently by soprano Anna Caterina Cornacchini accompanied by pianist Anant Changwaiwit who has become a regular performer at Ben’s. Billed as Favourite Puccini Opera Arias, the small stage was beautifully set up, the gleaming Yamaha piano taking centre pride of place with attractive crimson-red curtains set against a black background.

As well as being a singer, Anna Caterina Cornacchini is a multi-instrumentalist, choir director and composer. She graduated in 1999 from the Rossini Conservatory in the Italian city of Pesaro where she specialized in opera, viola and composing. She later won a scholarship to the prestigious Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna (Bologna Academy of Music) and holds a Master’s Degree in film music composition. She has performed in many important theatres and has taught in music schools in New York, Italy and China. For a time, she was a student of Luciano Pavarotti and has played many operatic roles. Last year she undertook a tour in China where she performed in twenty-five theaters in major Chinese cities.

The concert opened with the famous aria O mio babbino caro (“Oh my dear papa”) from the 1918 Puccini opera Gianni Schicchi. Anna Caterina gave a powerful rendition of the soaring melody and brought out the rich emotion of the aria. I enjoyed her dramatic stage presence, timing and sense of phrase, with a beautifully sympathetic piano accompaniment from Anant. The next item was the aria Si, Mi chaimano Mimi (“Yes, they call me Mimi”) from Puccini’s four-act opera of 1895, La Bohème. This is one of the composer’s most popular operas; set among the young crowd of artists and hangers-on living in the Latin Quarter of Paris in the 1840s. Anna gave a fine performance which brought out the drama of the aria and the haunting pianissimo passages were especially effective.

Anant Changwaiwit gave an atmospheric performance of a piano version of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s song Zdes’ khorosho (“How beautiful it is here”). It’s an arrangement by the Russian pianist Arcadi Volodos of a song from Rachmaninoff’s 12 Romances, Op.21 for voice and piano composed in 1901. Arcadi Volodos is one of the world’s most acclaimed pianists and predictably perhaps, the piano arrangement is technically demanding but Anant made the difficult music sound effortless.

From this point onwards, Anna Caterina departed from the printed programme, making it difficult for the audience to know what was going on. It became clear that she was not sure either. There were hasty discussions between each item and a general air of confusion. I received the clear impression that nothing had been planned and that the soloist was simply deciding the items on the spot, with little or no regard for the shape and continuity of the overall programme.

However, Anna gave a compelling performance of Un bel di vedremo (“One fine day”) from Madama Butterfly (1904), which was well-acted and brought out the tragic theme of the aria. In the opera, the aria is sung by Cio-Cio San (Butterfly) on stage with Suzuki, as she imagines the ship on the horizon bringing the return of her absent lover from America. It’s one of most melancholy moments of the entire opera. Anna gave the main theme a dramatic performance with plenty of energy and vocal power, much to the delight of the enthusiastic audience.

The Hungarian composer and virtuoso pianist Franz Liszt greatly admired the music of Verdi and in the years between 1855 and 1859, Liszt composed three piano works which were based on selections from two of Verdi’s operas. For Liszt, this was not a new idea, because apart from his own prolific output of music, he also wrote dozens of works based on music by other composers. He called the piano pieces based operatic “paraphrases” and drew freely from Verdi’s melodies create dazzling showpieces.

Anant gave a scintillating performance of Franz Liszt’s Concert Paraphrase on Verdi’s “Rigoletto” which is a brilliant but technically challenging piano solo. He handled the tricky staccato passages superbly and later in the work brought out the delicate melody which is heard beneath waves of chromatic rippling in the upper octaves. It was a superb display of virtuosity with striking dynamic contrasts and a compelling sense of pace. Anant has been a student at the College of Music, Mahidol University since 2007. In 2014, he received a Bachelor of Music Degree in Classical Music Performance with first-class honours and is currently studying towards a Master of Music in Performance and Pedagogy. Anant has performed the Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 2 with the Mahidol Symphony Orchestra. He has performed Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 and Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra.

The performers must have forgotten that the audience was expecting a programme of Puccini arias, for they then launched into two Neapolitan songs, and the connection with Puccini was not obvious, if indeed there even was one. The first was that old favourite, O sole mio (“My sunshine”) which dates from 1898. The melody achieved considerable fame in Britain in the 1980s when it was used in television commercials for a brand of ice cream. Anna Caterina gave a fine performance of the song and then provided a spirited performance of the second song, Funiculì, Funiculà. Composed in 1880 by Luigi Denza to lyrics by Peppino Turco it was intended to commemorate the opening of the first funicular railway on Mount Vesuvius. It became an instant hit, and after the sheet music was published it sold over a million copies within a year. Anna seemed to enjoy performing the song and accompanied herself on the castanets. It was a delightful performance which was much appreciated by the audience, helped along with a bright and lively piano accompaniment from Anant.

In complete contrast, Anant then played another of Liszt’s opera transcriptions, Liebestod the title of the final, dramatic music from the 1859 opera Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner. It is the climactic end of the opera, as Isolde sings over Tristan’s dead body. Liszt’s transcription dates from 1867 and the music represents Isolde’s emotional farewell as she joins Tristan in death. The transcription captures the beauty and drama of Wagner’s orchestral and vocal music, turning it into a powerful and expressive piano piece with flowing melodies, rich harmonies and emotional intensity. Anant gave a compelling account of this challenging work. As usual, his playing was brilliant and he created a wonderfully dark, atmospheric mood in the music. As so often happens in Liszt, the composer gives the performer an enormous technical challenge, to which Anant responded with a heroic performance. It was much appreciated by the attentive audience and brought the recital to a dramatic close.