Perhaps during the next few weeks, you might be thinking about buying a few bottles of bubbly. We tend to associate sparkling wines with celebratory occasions, because they are light, fizzy and frothy and seem by nature more suited to joyful glugging rather than thoughtful sampling. The bottles look rather special too, for they nearly always come with an expensive-looking silver or gold top foil that conceals the wire cage holding in the cork. Nothing looks more imposing on the table or bar than a few bottles of sparkling wine. In theory, you could make a sparkling wine from virtually any grape but some work better than others. There are hundreds of different sparkling wines made throughout the world, many of exceptional quality. Wine makers frequently offer at least one sparkling wine among their products and in recent years some excellent American sparkling wines have attracted attention.

In Europe, there are a few dozen sparklers which have become classics. France produces many, including Blanquette de Limoux which hails from the Languedoc region and made from the little-known Blanquette grape. Some French sparkling wines are known as crémant followed by the name of the place of origin. They are invariably high-quality wines, made using traditional methods. For example, Crémant de Bourgogne is from Burgundy and made from both Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. The fresh and fruity Crémant d’Alsace uses a wide variety of grapes including Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Riesling, Auxerrois and Chardonnay.

Italian Prosecco is made mostly from the Glera grape and the popular Moscato d’Asti, as the name implies, is made from Moscato grapes in the province of Asti. There’s the light and frothy Lambrusco, one of the few sparkling red wines. It comes from the north-east of Italy and made, not surprisingly, from the Lambrusco grape. Cava is the most popular sparkler in Spain and comes from the Penedés region and made from the obscure trio of Parellada, Xarel-lo and Macabeo. Sekt is the German word for the ordinary sparkling wines of Germany and Austria.

And then there’s Champagne. In his splendid book Wine, Hugh Johnson writes, “It was by some of neatest and most painless public relations the world has ever seen that champagne came into power. Somehow, at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, it just seemed to fall into its ready-made slot in the social pattern. What, we now must ask ourselves, did they drink at weddings, christenings, launchings…before they had champagne?”

You might be surprised to know that Champagne is a place; or more precisely an area, in and around the French city of Reims, which lies about ninety miles north-east of Paris. Around the city lie the Champagne villages (or crus) – about three hundred of them. And despite what the old song says, there was no single person who invented champagne. It evolved over many years as new technologies were developed. French regulations allow for seven different grape varieties to be used in making Champagne but the most common grapes used are Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. Chardonnay is a white grape of course, but the other two are red. If the Champagne is made from 100% Chardonnay it’s described as blanc de blancs.

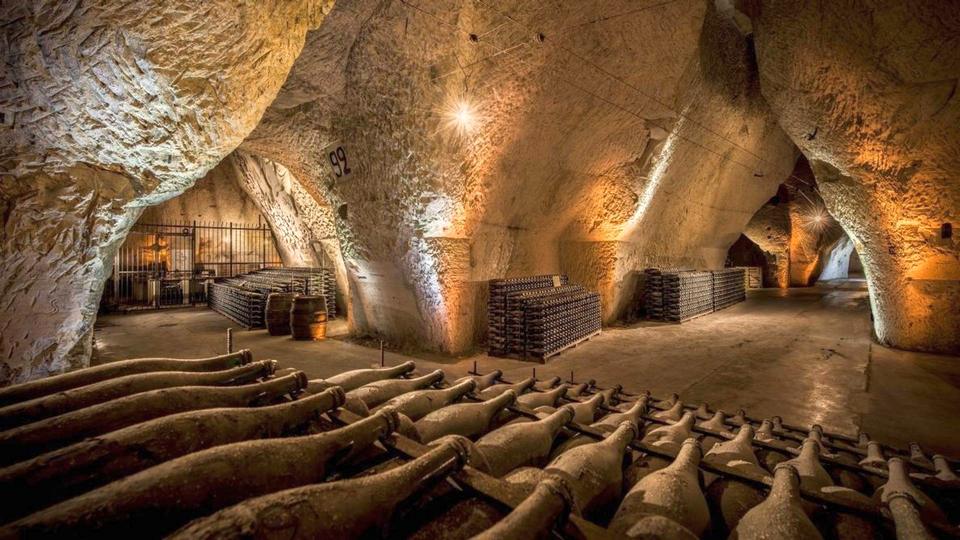

Champagne is relatively expensive for several reasons. For one thing, there is an enormous demand. In the USA alone, between 2019 and 2022 sales increased by more than 30%. The wine is made using a process known as the Méthode Champenoise which is lengthy, complicated and expensive. It is one of the most difficult wines in the world to make successfully. If these things interest you, there are several web sites that describe how Champagne is made.

There are over a hundred Champagne manufacturers or maisons (“houses”) as they are called. A couple of dozen, known as Grandes Marques, have achieved international fame and recognition. Each one makes wine of a particular and consistent house style. This is achieved by blending wines from different grape harvests, usually from three to five different years. For this reason, 95 percent of all Champagne is non-vintage and sometimes indicated by the letters N.V. on the label. The houses of Taittinger, Lanson and Bricout produce light-bodied Champagnes, whereas Charles Heidsieck, Moët & Chandon and Pol Roger specialize in more full-bodied wines. The boldest and fullest Champagnes come from Bollinger, Louis Roederer and Krug.

There are also “grower Champagnes” which are artisan wines made by the same people who grew the grapes. Unlike the major Champagne houses, whose major aim is consistency of style, growers have no need to go through the expensive and time-consuming process of standardization. This allows the grower to offer an individual product which is often cheaper. And incidentally, every bottle of Champagne carries a number preceded by a two-letter code which indicates the type of producer. For example, the code NM (Négociant-Manipulant) indicates that the wine comes from one of the large Champagne houses which buy their grapes from different growers then make the wine under their own brand. The code RM (Récoltant-Manipulant) indicates a grower Champagne.

But what is “vintage Champagne”? As the name implies, it comes from a single year. When the weather conditions in a particular year have been exceptionally good such as in 1995, 1996, 1999 and 2002 all the Champagne houses will release a vintage bottling. In less successful years, each house will make its own decision about whether to make a vintage wine. In contrast to non-vintage Champagne which must be aged for a minimum of fifteen months, vintage Champagne must be aged for a minimum of three years, this adding to the already high cost. Some producers age their wines for much longer. For example, Dom Pérignon releases its top-quality Champagne in three phases, known as Plenitudes. The first (P1) is aged for nine years, the second (P2) aged for 20 and the third (P3) aged for up to 40 years before release. These venerable wines are not cheap. The 1990 Dom Perignon P3 will set you back more than $4,500 (THB 154,000). And that’s just for one bottle. I tend not to drink it very often.

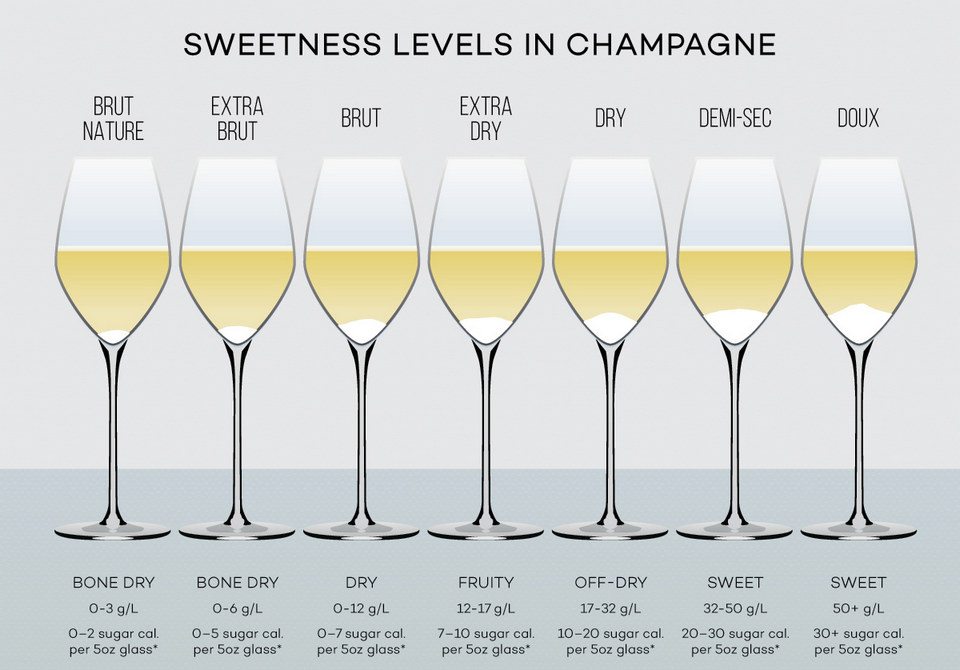

When you are buying Champagne or sparkling wines, it’s important to know the sweetness categories because they range from dry as the proverbial bone to the succulently sweet. The most popular is Brut which is medium dry.

If you are planning on buying some sparkling wine for the holiday season, there’s plenty of choice at all price levels. High quality Champagne will set you back about Bt. 3,000 per bottle. If you want something from the Grand Marques, you might need to pay up Bt. 4,000 baht and upwards. For example, Villa Market offers the famous Mumm Champagne Brut at Bt. 2,129; Charles Heidsieck Brut Reserve Champagne at Bt. 3,880 and Piper-Heidsieck at Bt. 3,980 but they also have some cheaper Champagne from the less-well-known names at under Bt. 2,000.

Wine Connection offers Bichat Brut at Bt. 1,599 as well as Prosecco and Cava. They also have the interesting Paul Martin Vintage Champagne at Bt. 1,999. Vines to Vino can supply the superb Bollinger Special Cuvée at Bt. 2,499; the Lanvin Brut Champagne at THB 1,399 and the Ernest Rapeneau Champagne Brut at only Bt. 1,199 (plus tax).

If you or your friends rarely drink Champagne, save your money and go for something more modest. Cava is a good choice and so is Prosecco; the obvious alternative to Champagne with a similar taste profile. It’s cheaper because it’s made using a process known as the Charmat Method in which the secondary fermentation takes place not in the bottle like Champagne, but in tanks. Most local outlets offer a choice of Prosecco brands, so it might be useful to buy two or three different ones and see which you prefer.

If you are a bit apprehensive about opening a bottle of Champagne (or any other sparkling wine for that matter), I can sympathize, because the pressure inside the bottle is about the same as that of a bus tyre. Never shake the bottle in the manner of Formula 1 racing car drivers. The cork should emerge with a gentle gasping “shlop” sound, not an explosive bang. That horrid popping noise instantly lowers the tone of any social occasion. Here’s an excellent video in which Erik Segelbaum demonstrates perfectly how to open the bottle easily and safely.

Sparkling wine tastes best at between 4-9°C (39-48°F) or slightly above refrigerator temperature. If in doubt, colder is safer. After opening, put the bottle in a wine bucket containing ice and water and if possible, leave it corked until it’s time to taste it. If you don’t manage to finish a bottle of sparkling wine at one session, you can leave it in the fridge for a short time. There’s no way you’ll get the cork back in again, but you can buy plastic air-tight stoppers with a pull-down lever that effectively seal the bottle. In this way, the wine stays fresh and the bubbles remain active for up to a couple of days. You can serve sparklers in either an ordinary wine glass or one of those tall, elongated tulip-shaped glasses, known technically as Champagne flutes. Forget those old-fashioned “saucers-on-a-stick” for they are completely useless for wine. Or, for that matter anything else.