It was a great pleasure to speak with the economist Prof. Steve Keen at the IDEA economics Asia launch in December.

Steve is one of only 13 economists in the world who predicted the global financial crisis.1 Not only that, he’s the chief economist of IDEA (of which I am an advisory board member) – a non-profit organization suggesting alternative solutions to the failing policy alternatives of quantitative easing and austerity measures which dominate central bank economics throughout the world today. Its board also includes respected economists Ann Pettifor and James K. Galbraith.

I’ve been reading a lot in the past year how the crisis is apparently over in some countries2 – even Mario Draghi, the head of the European Central Bank, has said so!3 From what Steve said during his talk in December, he shares my lack of faith regarding Draghi and others. Anyone who has read the excellent Lords of Finance4 by Liaquat Ahamed would know that we’ve only come full circle and returned to our roots when central bankers are once again ostracized as little more than charlatans, as they were following the Great Depression and World War II, two catastrophic events for which they were largely responsible.

So forgive my scepticism when I read that apparently quantitative easing (QE) has saved the day. According to some sections of the media, QE involves central banks printing money5. Central banks claim that eventually this new money gives incentive to financial companies to lend to business and individuals, stimulating spending.6

The ‘printing money’ claim is just not true. What the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan and the Bank of England have been doing is buying assets, such as bonds, mainly from non-bank financial companies. Instead of using the huge amounts of cash received, these financial institutions did not pump it into the economy as a whole: their traders started to speculate with it to bring in greater returns. The London Whale case is one example of what has been happening.7

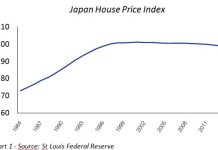

Any claim that QE has given people confidence to borrow money again is blown away by a look at the Federal Reserve’s own data. There was indeed a spike in private borrowing but that was temporary and soon tailed off back to immediate post-crisis levels (see chart 1).

Chart 1 – Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

Chart 1 – Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

The effect of QE on the overall economy has been minimal. In 2010, then Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke claimed that, “Higher stock prices will boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending. Increased spending will lead to higher incomes and profits that, in a virtuous circle, will further support economic expansion.”8

I don’t claim to be an expert in behavioural science but I really don’t see the connection between stock market prices and consumer confidence. If I hear on the news that the prices on the TSE, the SET or the S&P have gone up, it doesn’t inspire me to go out and buy anything. I’d hazard a guess that it’s disposable income and confidence in paying back credit that influences our purchasing decisions. But I’m not the head of a central bank.

One of the many interesting things mentioned by Steve at the event is the incredible practice of conventional economists to ignore private debt levels. They do this on the assumption that it represents a “pure redistribution” which should have “no significant macroeconomic effects” – as described by none other than Ben Bernanke.9

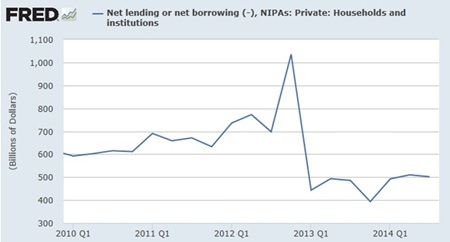

Frankly, this suggestion is absurd. I would venture to say that the rate of unemployment is a significant microeconomic indicator. A quick look at empirical data in the US since 1990 reveals that there is a massive correlation (0.93) between private debt levels and unemployment (see chart 2).

Chart 2

Chart 2

It is incredulous that, in spite of the global economy crashing under the colossal weight of debt, central bankers of major economies universally refuse to challenge the status quo. What is more worrying though, is that there are indications that another crisis is looming and we still haven’t learnt how to deal with the current situation.

It’s difficult to say when the crisis will come, or what will trigger it, but the recent crash in oil prices has all the hallmarks of such a trigger.

Some analysts believe that lower crude oil prices will act as a catalyst to make the booming shale oil industry more efficient.10 That’s all very well, but the rise in the shale oil industry has been financed by junk bonds.11

Junk bonds. Remember those? High-yield bonds with a high risk of default. In 2008, illiquidity of junk bonds – repackaged and backed by overvalued subprime mortgages – led to the GFC. A J.P. Morgan analyst estimates that, should prices for crude oil remain at the relatively low level of around US$65 a barrel for the next three years or so, up to 40% of all energy junk bonds could default.12 He added that even if default rates hovered at 20% to 25%, the consequences would be “dire”.

In fact it doesn’t necessarily take actual default to trigger a crisis. Merely the threat of default can make bonds illiquid: if everyone is trying to get out of them at the same time, no-one wants to buy them.

Does this mean we’re heading for the abyss?

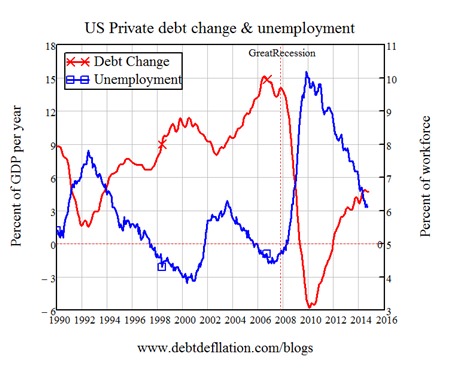

Possibly, but more likely Japan. If there isn’t a fundamental re-think amongst central banks, we could well be facing a prolonged period of deflation, with low economic activity as products and materials become less affordable. If that sounds familiar, that’s because it’s been happening in Japan for the last 25 years.

Since 1990, each tentative revival in Japan has given way to another collapse back into recession. This has happened because the Japanese government uses QE to stimulate the economy; just as the economy shows shoots of recovery, the government tries to reduce its own haemorrhaging debt. That starts a return to private sector deleveraging – where the rate of change of private debt is actually negative. This takes money out of the economy, and causes another recession. To offset this the government invests a fortune to provide stimulus and so it continues.

The US – and, given their penchant for QE, the UK – look likely to fall into this private debt trap. So, while 2015 may see some economic revival, it will be just a part of the vicious cycle.

Footnotes:

1 http://barnabyisright.com/2013/05/30/an-historical-warning-

for-proponents-of-a-modern-debt-jubilee

2 http://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesgruber/2014/01/29/

welcome-to-phase-three-of-the-global-financial-crisis/

3 http://www.marketwatch.com/story/euro-zone-crisis-

over-at-least-the-financial-crisis-is-2014-04-09

4 Liaquat Ahamed, Lords of Finance: The Bankers

Who Broke the World, Penguin, 2009.

5 http://www.torontosun.com/2013/03/28/printing-

money-doesnt-make-sense

6 http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/

quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

7 http://www.bloombergview.com/quicktake/the-london-whale

8 http://www.forbes.com/sites/robertlenzner/2014/06/20/the-fading-

out-of-the-feds-qe-bond-buying-may-mean-the-end-of-a-5-year-bull-market/

9 Ben Bernanke (2000), Essays on the Great Depression.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

10 http://fortune.com/2014/12/08/oil-prices-drop-impact/

11 http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2014/12/01/falling-oil-

prices-could-lead-to-massive-junk-bond-defaults/

12 ibid

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook: /MBMGGroup |