Many of Shinzo Abe’s fellow party members disagreed with his decision1 when he dissolved the Diet in November. But the gamble paid off and he has won another term to become one of Japan’s longest-serving Prime Ministers.

Calling a snap election may have been a shrewd political move but it also raised questions about the timing, given Japan’s current economic state. “Now is not the time to dissolve the Lower House,”2 said Hiroshi Shikanai, Mayor of Aomori – a city in the north of Japan’s largest island, Honshu. “We’re faced with issues that require co-operation between the central and local governments, such as measures to boost regional economies and fight population decline, but the election will create a vacuum,” he added.

The Land of the Rising Sun is certainly in a situation which is a far cry from the heady days of the 1980s boom period, when the Japanese corporate world was nicknamed Japan Inc. because of the close relations between the business sector3 to the government, which seemingly aided the former in exporting goods.

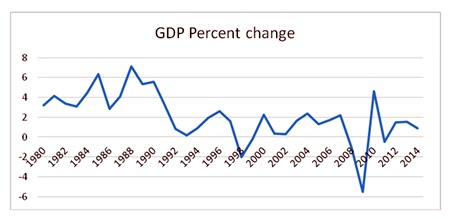

When in the late 1990s Japan’s huge post-war economic growth came to a halt and the asset price bubble burst, the government’s reaction was to embark on public works projects to stimulate demand. These projects included massive spending on roads but only resulted in a huge increase of public sector debt and the economy continuing to stagnate (see chart 1).

Chart 1

Chart 1

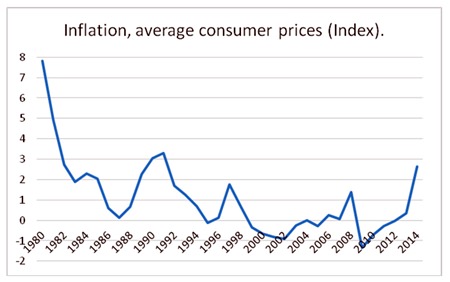

The next attempt to check the slump was to implement structural reforms; but these only led to deflation. Falling prices may sound like a favourable thing, particularly when it comes to the cost of living. However, it is bad news if you have investments, it increases the real price of any debts and can counterbalance the shoots of economic recovery (see chart 2).

Chart 2

Chart 2

In 1998 Princeton economics professor Paul Krugman published a paper entitled Japan’s Trap, which recommended embarking on a policy to boost inflation and thus cut long-term interest rates and promote spending, even though this was precisely the form that Japanese policy took in the 1930s under Korekiyo Takahashi’s finance ministry, and we all know where that led.

In the early 2000s, the government embarked on its own version of Krugman’s recommendations. The policy came to be called quantitative easing and was not about printing huge amounts of new money, but in fact increasing the money supply in the banking system by buying bonds and similar products.

The effect of this was some small improvement in demand; however, deflation remained. That hasn’t stopped the Bank of Japan though, which has continued to implement quantitative easing policies ever since. If you thought the Federal Reserve was dogmatic, the Bank of Japan is on a different level altogether.

Footnotes:

1 http://www.economist.com/news/21636467-shinzo-abe-wins-easily-weak-mandate-voters-romping-home

2 http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/11/21/national/politics-diplomacy/mayors-governors-cast-doubt-on-abes-dissolution-gambit/#.VJFGi7QcSM8

3 http://www.investopedia.com/terms/j/japaninc.asp

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: info@mbmg-group.com; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook: /MBMGGroup |