With the breakdown of money economy the practice of international barter is becoming prevalent.

– John Maynard Keynes, the Economic Consequences of the Peace, 1920

Every October in Greece, blue-and-white national flags go up on almost every public building and residence, as well as on the front of buses.

This is to commemorate ‘Oci (No) day, the day in 1940 when the Greek population collectively raised its eyebrows, gave a large tut and said ‘No’ to the Axis powers’ demands to enter Greek territory.

Parallels can be drawn with the Greek debt crisis today. Historical images of plucky little Greece standing up to powerful adversaries may come to mind – especially with German tabloid newspaper Bild lampooning the Greek Prime Minister1 and Finance Minister2 and its Greek counterpart Dimokratía making references to Nazism.3

Added to this, the Greek Prime Minister recently claimed €160 bn in compensation for a forced loan to German occupiers and destruction of Greece’s assets during World War II.4

Whilst it may be of little help right now to look into Europe’s murky past, one more recent reference could provide some light at the end of the tunnel – and it comes from right here in Asia.

Asian Financial Crisis

In July 1997, the inability of the Thai authorities to continue to defend the Thai Baht precipitated the Asian Financial Crisis. This led to both a period of initially painful adjustment and then sustained economic growth and prosperity and also to a rethink of financial regulatory systems across Southeast Asia. Arguably, the region was also more protected from the aftershocks of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) because of actions taken a decade before. Interestingly, there are some similarities between Asia in 1997 and Greece today.

Boom as a pretext

In the run-up to 1997, Thailand had been enjoying an economic boom: the average year-on-year GDP growth rate between 1987 and 1996 was 9.5%.5 In fact there had been similar economic trends across the region in the 1980s and 1990s.6 (See graphs 1 & 2)

Graph 1 Source: IMF

Graph 1 Source: IMF

Graph 2 Source: IMF

Graph 2 Source: IMF

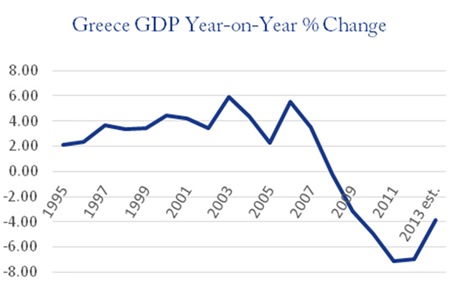

In the ten years leading up to the GFC, Greece had seen an average year-on-year rise in GDP of 4%.7 Its growth rate was higher than all other Eurozone countries, except Ireland and Luxembourg. This didn’t last, however: by 2008 it had dropped to just 0.2% year-on-year.8 (See graph 3)

Graph 3 Source: IMF

Graph 3 Source: IMF

In turn, Greece’s sustained economic boom and a lack of competition in domestic goods and services markets kept wage and price inflation consistently above Eurozone averages.9

Heavy borrowing

With the expansion of Southeast Asian economies came a huge increase in credit extensions – at a rate far higher than their GDP. A lending boom resulted, which expanded so rapidly that it ended up with excessive risk-taking, eventually to leading to heavy losses on loans.10

Greek public debt has been through the roof for some time, especially between 2000 and 2011 – it jumped by 50.5% in 1 year between 1999 and 2000, and has averaged at 8% more per year since 2000.11 The reason for such an increase before the GFC is that global credit conditions in the 2000s allowed Greece easy access to foreign borrowing12, although post GFC the increase in debt to GDP also reflects the contraction of GDP.

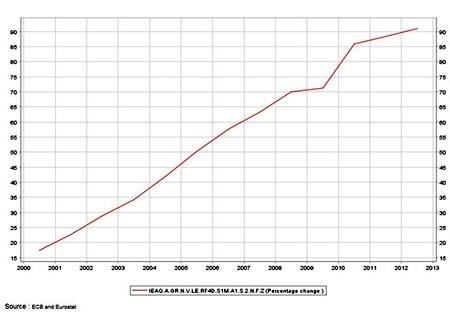

Whilst ECB and IMF reports use government debt as one of their main indicators, the level of household debt is more significant – especially as the crisis affects people as well as government, but also because private debt is a far greater driver of economic activity than government spending.

Liberalization of financial services in Greece triggered strong growth in private credit. This served to boost household consumption13 but it also put people in debt to jaw-dropping levels.

According to ECB figures,14 the ratio of household loans to disposable income jumped from 17.32% in 2000, to 90.95% in 2012. (See graph 4)

Graph 4

Graph 4

Fixed Currencies

For more than 40 years, the Thai Baht was pegged to the US Dollar. The fixed exchange rate had been changed three times, the last of which came in 1984 when the rate went from THB 20.8 = USD 1, to THB 25.15

External factors such as devaluations in China and Japan, a decline in semiconductor prices left the region’s economy vulnerable. The region’s financial structures were weak, leaving them at risk if there were a sudden withdrawal of capital.

That happened in 1997, as a net capital inflow of 6% of GDP in 1995 turned into a 2% outflow in 1997.16 Such a quick turnaround, coupled with a strong US economy, triggered a run on the Thai Baht and then on the Korean Won.17 Market confidence plummeted, the Baht was floated on 2nd July 1997 and its value had depreciated by 50% at the end of the year.18 The Won had been a managed floating currency and after 1990 its exchange rate with the USD fluctuated within certain parameters.

Having floated the Baht, the Bank of Thailand brought the currency to its ‘natural’ level and made exports more competitive, thus bringing in foreign currency. In January 1998, the Baht reached 55 to the US Dollar.19

As we stand, Greece does not have the luxury of floating. It no longer has its own currency and its monetary policy is mainly controlled by the ECB in Frankfurt. The only roles Greece’s central bank, the Bank of Greece, has today are printing Euros within Eurozone rules, selling gold sovereigns and trying to maintain price stability.

In the last ten years when the Bank of Greece was in charge of the whole system, the consumer price index (CPI) had fallen year-on-year from a catastrophic 18.02% in 1991 to 3.05%20 when it gave up most of its powers to the ECB in 2001. So, in spite of its previous difficulties in the 1980s and 1990s, it must have been doing something right.

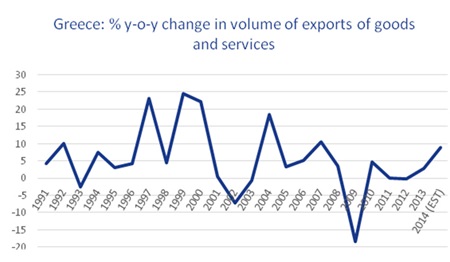

What is noticeable is the difference in exports once Greece had joined the Euro. Year-on-year percentage changes had been volatile for a long time beforehand but, apart from a brief recovery in 2004, volumes went south. Even though there have been slight upturns since 2010, they are a world away from pre-Euro levels. (See graph 5)

Graph 5 Source: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2015

Graph 5 Source: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2015

Footnotes:

1 https://pbs.twimg.com/media/B-McbwHCQAAHyin.png

2 http://www.bild.de/politik/ausland/yanis-varoufakis/

der-luegner-40198380.bild.html

3 http://www.thejournal.ie/memorandum-macht-frei-how-

one-greek-paper-views-the-second-bailout-351455-Feb2012/

4 Financial Times: http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/14c4da36-

c812-11e4-8210-00144feab7de. html?siteedition=intl#axzz3 UhUdMRTp

5 IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2015

6 Recovery from the Asian Crisis and the Role of the IMF, IMF 2000,

https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/062300.htm

7 Eurostat

8 Idem

9 IMF Country Report No. 13/156

10 Frederic S. Mishkin, Lessons from the Asian Crisis, NBER Working Paper No. 7102, April 1999, JEL No. F3, E5, G2

11 IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April, 2015

12 IMF Country Report No. 13/156

13 idem

14 http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/quickview.do?SERIES_KEY=

158.IEAQ.A.GR.N.V.LE.RF4D. S1M.A1.S.2.N.F.Z

15 XE.com

16 Recovery from the Asian Crisis and the Role of the IMF, IMF 2000,

https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/062300.htm

17 http://www.columbia.edu/cu/thai/html/financial97_98.html

18 idem

19 http://www.tradingeconomics.com/thailand/currency

20 www.inflation.eu

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook:/MBMGGroup |