In Part 1, I compared Greece’s current predicament with the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. In the second part of the article, I look at how the IMF helped Asia out of crisis, what lessons it learned and whether these are or could be applied to Greece.

Solutions for Asia…

With the export figures in mind, and the fact that nothing can be done on a local level to counter the issue, it is worth noting that there is nothing to prevent Greece from pulling out of the Euro. Neither the founding EU Treaties nor the latest (Lisbon) Treaty make any provision for withdrawal from European monetary union.1 Even the people at the ECB cannot find a legal obstacle.2 Of course, while this may make some economic sense, it will eventually come down to political will – as did joining the Euro in the first place.3

In its 2000 report on the Asian Crisis,4 the IMF took a critical look at the effectiveness of its programmes to the countries affected. It categorised its assistance into four main parts:

* Tight monetary policies

* Fiscal objectives

* Structural reforms

* Clear government guarantees of bank deposits.

The IMF report concluded that, when firmly applied, tight monetary policies reversed pressures on the exchange rate and prevented inflationary spirals. In Korea and Thailand, the result was negative real interest rates; however, it also resulted in currency depreciation and rising inflation. So much so that, after a brief period, interest rates were raised to high levels bringing about stable markets and currency levels.5

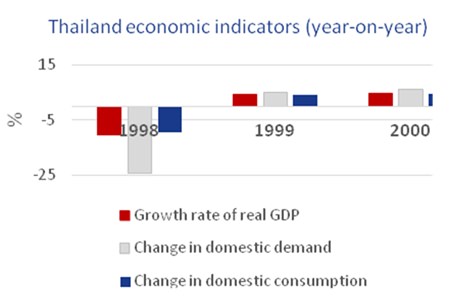

The IMF now believe that the programme’s initial fiscal objectives were too tight: the affected countries’ economies were contracting and private demand collapsed, creating “massive current account surpluses.”6 This makes sense, as if a government tries to recoup more money, it is the private sector which will naturally have to pay. This then has the effect of reducing demand, as noted by my colleague at IDEA economics, Prof. Steve Keen in IDEA’s Outlook 2015 paper.7 Having noticed this, and recognizing that Thailand, Indonesia and Korea all had strong fiscal positions and low public debt before the crisis, the IMF eased its fiscal requirements to prop up demand.8 In Thailand’s case, this certainly seems to have worked. (See graph 1)

Graph 1 Source: National Statistics Office, Thailand

Graph 1 Source: National Statistics Office, Thailand

The IMF’s demands for financial sector reform varied according to the country. However, there were three common threads across Thailand, Indonesia and Korea: closing insolvent financial institutions; recapitalization of potentially viable ones; close supervision of weak financial institutions by the central bank; and a strengthening financial supervision and regulation up to international standards.

Although these measures were implemented, the IMF’s report suggests that the organization’s initial requirements didn’t focus sharply enough on the financial sector and corporate issues; and that pace and sequencing would need to be perfected in future cases.9 Especially, cynics might argue, if those future cases occur in developed economies whose citizens may be less willing to suffer the economic hardship inflicted on the citizens of South East Asia.

In reforming the financial sector, it became evident to the IMF that governments must give clear guarantees of bank deposits. During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, 16 Indonesian banks were closed down to prevent haemorrhaging of public money to support them. However, no guarantee of bank liabilities was announced until January 1998, creating public anxiety.10

… why not remedies for Greece?

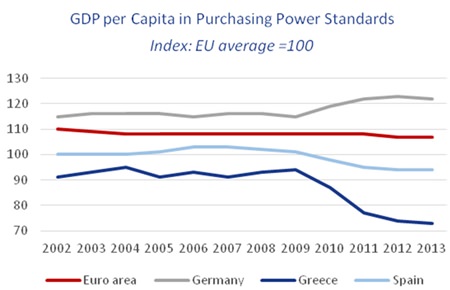

If the IMF recognized that tight monetary policies were seen to be adversely affecting demand in Asian economies, why on earth is Greece being put through austerity measures now? It is clear that these measures have not helped the Greek economy emerge from its post-crisis troubles. In fact by 2013, Greeks were almost 20% poorer than the average EU citizen than back when the Euro began in 2002.11 (See graph 2)

Graph 2 Source: Eurostat

Graph 2 Source: Eurostat

Similarly, a bank run was narrowly averted in Greece in February 2015: the Greek government was locked in talks with the IMF and other creditors and the lack of progress made bank depositors nervous. During negotiations, Greek companies and households removed EUR 7.6 bn from their bank accounts, reducing Greek bank deposits to their lowest levels in 10 years.12 The risk is apparent again: although Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis is hopeful a deal will be reached by 5th June – the next repayment deadline – he has admitted that Greece does not have the funds to make the payment.13

Yanis, along with some of the other leading characters in this latest Greek drama, is well-known to and highly regarded by the IDEA Economics team. However, some of us, or at least I certainly do, disagree with his deep and undoubtedly sincere commitment to keeping Greece in the Euro. Yanis would be very unlikely to initiate a unilateral exit from the single currency; however, it may not be his choice to make for much longer.

On 1st April of this year, the Greek government submitted a 26-page proposal14 to its lenders (the Brussels Group – IMF, European Commission and ECB), which included structural reforms to the financial services sector. These proposals included outlining a strategy to ensure stability of the Greek banking system; giving the Bank of Greece more power in consumer protection; and tackling the non-performing loans problem. However, this document was rejected by the two organizations because it “lacked detail and substance”, according to one EU official.15 On reading the document, I have to conclude the Brussels Group was right in this instance.

That said, surely this is an opportunity for the IMF to take the lead, as it did in Asia, and set out structural reforms which it saw work in 1997. Thailand is now ranked a creditable 27th globally in the Regulation of Securities Exchanges and a decent 37th in Soundness of Banks according to the World Economic Forum’s 2014-2015 Global Competitiveness Report.16

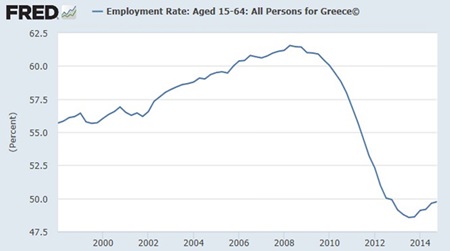

Instead of working with Greece to tackle its issues, it seems from the outside that the IMF is at the table – along with its Brussels Group colleagues – merely waiting to reject another new proposal from Greece17 and demand full payment whatever the consequences. Meanwhile normal people in Greece suffer (e.g. unemployment levels). (See graph 3)

Graph 3 Sources: St. Louis Federal Reserve & OECD

Graph 3 Sources: St. Louis Federal Reserve & OECD

When it comes to historical analogies, perhaps it is more useful to look not to 1940 but to 1919, when in the Paris Peace Talks an entire nation was stripped of what liquid wealth it had and was demanded to make “impossible payments for the future.”18 That nation, by the way, was Germany.

| “I cannot leave this subject as though its just treatment wholly depended either on our own pledges or economic facts. The policy of reducing Germany to servitude for a generation, of degrading the lives of millions of human beings, and of depriving a whole nation of happiness should be abhorrent and detestable, – abhorrent and detestable, even if it were possible, even if it enriched ourselves, even if it did not sow the decay of the whole civilized life of Europe. Some preach it in the name of Justice. In the great events of man’s history, in the unwinding of the complex fates of nations Justice is not so simple. And if it were, nations are not authorized, by religion or by natural morals, to visit on the children of their enemies the misdoings of parents of rulers.” – John Maynard Keynes, the Economic Consequences of the Peace, 1920 |

Footnotes:

1 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/collection/eu-law/treaties.html

2 http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scplps/ecblwp10.pdf

3 http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/1095783.stm

4 Recovery from the Asian Crisis and the Role of the IMF, IMF 2000,

https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/062300.htm

5 idem

6 idem

7 http://www.ideaeconomics.org/blog/2015/1/13/steve-keens-2015-outlook

8 Recovery from the Asian Crisis and the Role of the IMF, IMF 2000,

https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/062300.htm

9 idem

10 idem

11 Eurostat

12 http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/b27058d4-d3d7-

11e4-99bd-00144feab7de.html#axzz3b7i5q8y1

13 http://www.wsj.com/articles/greece-will-make-its-

next-imf-payment-says-yanis-varoufakis-1432657288

14 http://im.ft-static.com/content/images/55b27a7e-

d87c-11e4-ba53-00144feab7de.pdf

15 http://www.euractiv.com/sections/euro-finance/greek-

reform-list-fails-impress-lenders-313491

16 http://www.weforum.org/reports/global-competitiveness-

report-2014-20159bc55d1da1d5=RootFolder%3D% 252F

personal%252Fsimon%255Fh%255Fmbmg %252Dgroup%

255Fcom%252FDocuments%252FMBMG% 2520IA%2520Updates

17 http://www.rte.ie/news/2015/0525/703622-greece-bailout/

18 John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Chapter IV, Part III, 1920.

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook:/MBMGGroup |