Is the Australian property market truly resistant to a bubble burst, or is it just a disaster that’s taken a while, but is now ready to happen?

For the last five years or so, I’ve been warning about a future crisis in Australia. So far, it hasn’t come to anything. But that doesn’t mean to say that the danger has passed.

That’s because this economic threat comes in the form of a housing price bubble. As any student of 2008, or even medieval and ancient history, will tell you – bubbles don’t go away. Instead, they just inflate and inflate. The problem is we never really know when the maximum capillary length has been reached and the whole thing pops, taking investors with it.

In Australia, the bubble began with the deregulation of the financial sector from 1985. This removed lending controls on banks, with the aim of opening financial markets up to greater competition, allowing savers to earn more interest and borrowers to take on loans at lower rates of interest.1 This created a new low-inflation, low-interest-rate economic environment in Australia.2

This sounds all very good in theory: more competition in the banking sector means a better choice for customers, as commercial banks vie for market share. The problem is that when it comes to loans, as individuals, we don’t necessarily know the full implications of what’s on offer – as we all saw with the US subprime crisis in 2007/2008.3

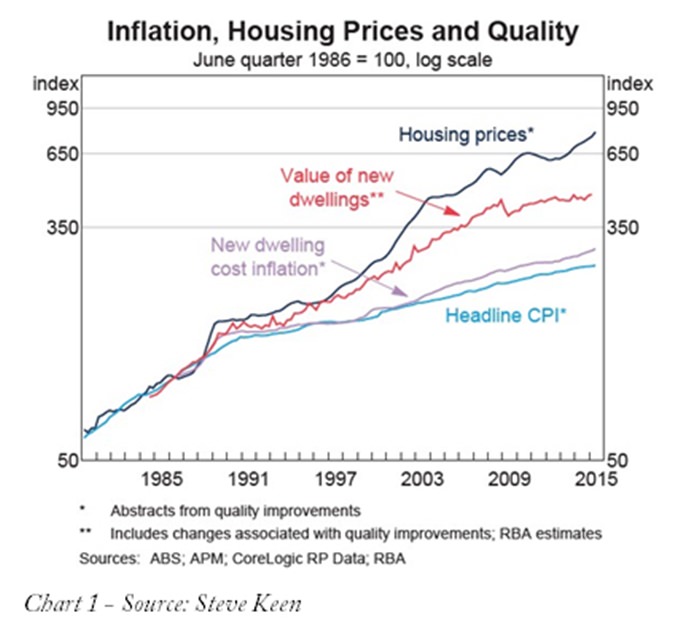

Once people get easier access to mortgages, house prices go up (see chart 1). As house prices go up, people have to borrow more to buy a place to live. In the face of escalating prices, the government embarked on a series of First Home Owner Grant programmes. The amount depends on the state: most give out between A$10,000 and A$15,000 towards a place and the Northern Territories government offers A$26,000.

Yet again, though, this helping hand has contributed to a further increase in the price of a home at a rate way above inflation and actual values.

In just the first nine years of the grant scheme (2000-2009), the public sector contributed A$200 million to the housing market to date. Yet, at the same time, there was a A$2.8 billion increase in mortgage debt – Australia’s sub-prime lite as Steve Keen, my colleague at IDEAeconomics, called it.4

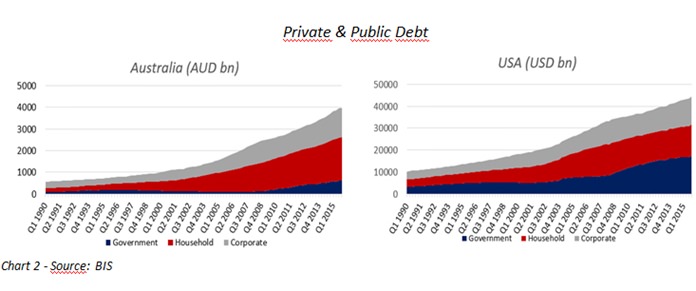

The consequence of all this is spiralling household debt; which Australia has been experiencing since the early 1990s (see chart 2).

The global economic situation doesn’t help Australia either: largely due to asset values and interest rates. Overall, share prices have risen significantly over the last seven years. This was particularly true between 2009 and 2013 when, then Federal Reserve chairman, Ben Bernanke used quantitative easing to deliberately push up stock prices, in an attempt to boost US economic growth.5

To be continued…

Footnotes:

1 http://fsi.treasury.gov.au/content/downloads/PubSubs/000090d.pdf

2 See ABS data

3 http://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/09/financial-crisis-review.asp

4 http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/03/22/fhb-boost-is-australias-sub-prime-lite/

5 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/11/03/AR2010110307372.html

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation.

MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: |