This week and next we have part 2 in a special report from Tim Price, Director of Investment with PFP Wealth Management.

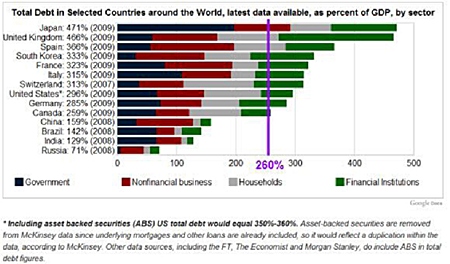

Investment conclusion #2: while it doesn’t make sense to hold the debt of bankrupt countries (see graph 1 for some of the more visible culprits), it makes sense to own bonds issued by the most creditworthy sovereigns. Particularly if Soc Gen’s Albert Edwards is onto something with his deflationary “Ice Age” prognostications. The Edwards thesis, in brief, is that in a cooling global economy, equities de-rate in isolation and versus government bonds, which re-rate in absolute terms.

These charts come via Chris Martenson and his excellent blog. A recent post, the self-explanatorily titled “Death By Debt”, makes the damning point that we are all trapped in an expanding credit system that has run into its terminal phase. We are used to living in a financial environment in which credit has grown exponentially. Global debt has been growing in a “nearly perfect” exponential fashion throughout the 1970s, the 1980s, the 1990s and the 2000s.

“In order for the 2010 decade to mirror, match, or in any way resemble the prior four decades, credit market debt will need to double again, from $52 trillion to $104 trillion.”

Needless to say, this is not going to happen, although there would appear to be politicians, presidents, intransigent single currency blocs and bankers out there who believe it might.

Graph 1

Graph 1

“It explains why Bernanke’s $2 trillion has not created a spectacular party in anything other than a few select areas (banking, corporate profits) which were positioned to directly benefit from the money. It explains why things don’t feel right, or the same, and why people are still feeling queasy about the state of the economy. It explains the massive disconnects between government pensions and promises, all developed and doled out during the prior four decades, cannot be met by current budget realities.

“Our entire system of money, and by extension our sense of entitlement and expectations of future growth, were formed during, and are utterly dependent on, exponential credit growth.

“What will happen when credit cannot grow exponentially? .Debts cannot be serviced, the weaker and more highly leveraged participants get clobbered first (Lehman, Greece, Las Vegas housing, etc.) and the dominoes topple from the outside in towards the centre. Money is dumped in, but traction is weak. What begins as a temporary programme of providing liquidity becomes a permanent programme of printing money needed in order for the system to merely function.”

Note that Martenson uses the word “function” as opposed to, say, “thrive”. This is because the system has gone beyond the point of no return.

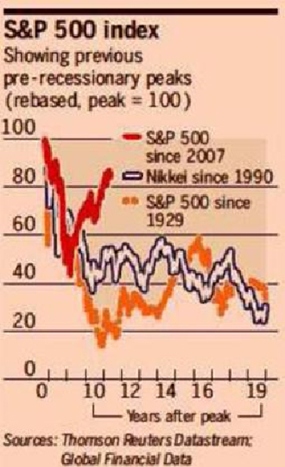

Graph 2

Graph 2

Fed chairman Bernanke during his June 7th address at the International Monetary Conference in Atlanta made no explicit mention of introducing QE3. He did concede that monetary policy rates would be kept at exceptionally low levels for an extended period, but we already knew that. Like a consistently spoilt child, the equity market didn’t like what it heard and went into a sulk. But there is merit in looking beyond the short term to see the longer term trend. The Financial Times published graph 2 in its weekend edition last month.

Its impact may not be immediately clear, so let us try and spell it out like crystal. After two previous historic busts, the S&P 500 (1929 to 1948) and the Nikkei 225 (1990 to, well, today) spent the subsequent two decades losing up to 80% of their value. In other words, after a colossal boom and a once-in-a-generation collapse, equity markets can and will disappoint all those taught to believe in stocks for the long run.

The last several years (the bounce in the red line for the S&P 500) would seem to diverge from the historic path implied by the other two graphs. Perhaps the recovery of the last two years was a false one, bought by the trillions of stimulus poured into the market by a desperate Fed? Time, as always, will tell.

But if the comparison is a fair one, and we think it is, it is also time to reflect on what a sensible allocation to equities should be in the context of a balanced portfolio positioned primarily for capital preservation. The good news (if any) from the chart is that there is time for this reflection before deciding just how much, and how fast, to get out of Dodge.

The above data and research was compiled from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither MBMG International Ltd nor its officers can accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the above article nor bear any responsibility for any losses achieved as a result of any actions taken or not taken as a consequence of reading the above article. For more information please contact Graham Macdonald on [email protected]