Professor Bernanke’s academic lack of interest

Even proponents of the policies that have taken the global economy to the brink, such as Bernanke’s predecessor Alan Greenspan, admit that these policies are a huge experiment, lacking any scientific grounding or precedent.

Indebted western economies currently remain deeply mired in the depths of Kondratieff’s winter despite the unconventional stimulatory economic policy and smorgasbord of bailout packages. The three asset classes which perform best during this winter phase are, as previously stated, gold, bonds and cash. Gold has already risen from below USD250 per oz to a peak of USD1901.35 per oz last year. It has the potential to climb rather higher than that before the end of the winter period, but it also, in the longer term, appears inevitably condemned to fall back below USD1000 per oz, meaning that investors holding gold need to keep an eye firmly on the exit door. Bonds and cash each face the horns of a vicious dilemma.

The Dilemma

Central bank policy has created a feedback loop where, in a kind of Pavlovian nightmare, investors are, in the short term punished for prudent, strategically appropriate asset allocations and rewarded for wild, excessive and speculative behaviour. Sadly, unless you are prepared to take a leap of faith based on blind belief in the power of central banks, this will inevitably end in the failure of these government sponsored speculative excesses. It is a difficult challenge for many portfolio managers, let alone individual investors, to maintain the required focus, understanding and discipline in the face of such manipulations. The best performing portfolio managers ask two key questions –

* Which asset classes offer better risk/reward than cash?

* How to get the best cash returns?

US Bond and T-Bill rates dictate both global interest rates and investment returns, but one month T-Bills now pay annualised interest of just 0.05% and one year bonds just 0.13%, a negative real return once inflation is factored in. The benchmark 10-year note has been gyrating around the 2% per annum level for some time. To get a 3% annual return you have to buy long-dated (30 years to maturity) treasuries with the added caveat of price volatility between now and maturity, i.e. if interest rates increase by just 1% then the capital value of 10-year notes would instantly fall by the best part of 10%. For thirty year notes the price drop would be almost three times as bad. This becomes even worse if interest rates increase more.

| Date | 1 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 yr | 2 yr | 3 yr | 5 yr | 7 yr | 10 yr | 20 yr | 30 yr |

| 2/1/2012 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.72 | 1.27 | 1.87 | 2.65 | 3.01 |

Flawed theory: Bonds and Bernanke’s blind man’s bluff

Bond prices have pretty well reached their apex with interest rates on US Treasury Bills having fallen to almost zero. This is likely to endure for as long as Bernanke & Co. continue to press ahead with flawed stimulus policies.

Although negative real rates (interest rates minus inflation) look as though they are here for some time and longer term rates (such as 30-year government bond rates) can fall, especially if manipulated by government policies, interest rates look certain to move higher over time thus pushing down the price of bonds. While this scenario may not be imminent – MBMG’s near term expectation is for prices to continue to increase – it is all but inevitable, and may be dramatic once it takes root, so investors need to know where the exit door is located.

Given the heightened risks surrounding investing in gold or bonds, cash emerges as the hardiest asset class in times of economic winter despite the pressure that investors face to chase higher-yield/higher-risk investments. This is the ultimate central bank manipulation and is generally justified by reference to a range of economic theories including The Taylor Rule which is a formula developed by Stanford economist John Taylor in 1993. It was designed to provide central banks with guidance on setting interest rates in response to changing economic conditions by systematically reducing uncertainty and increasing the credibility of the central bank’s future actions through the process of fostering predictable price stability and full employment.

One of the key elements of the theory is that any rise or fall in inflation should at least be matched by relative increases or decreases in base interest rates, thereby dampening growth with higher interest rates when growth leads to inflation, or by stimulating economic activity (spending and investment) by cutting rates in times of low growth. As it is not possible for interest rates to drop below zero, an implied negative rate from Taylor’s Rule would seem to justify “printing money” – the introduction of new money supply by central banks, now universally known as Quantitative Easing (QE) – as means of stimulating growth.

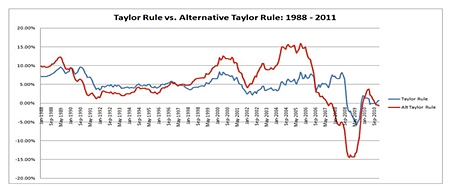

A problem arises, however, from the fact that in 1999, Taylor wrote a further paper in which he discussed and tested a number of variants to his original theory. It is these variants that have been cited by Bernanke when defending his fiscal and monetary policies. This strongly contrasts with Taylor’s position as he is now distancing himself from these departures to his original theory due to their failure to stand up to historical experience and investigation (see graph this page).

Specifically, the variants of Taylor’s Rule suggest very different responses to the financial crisis. Whereas Taylor insists that his original theory, which better stands up to historical evidence, suggests only limited QE in the initial stages of a financial crisis, Bernanke is citing an unproven or even discredited variant of the rule, which is based on forecasted rather than actual inflation and a larger gap between actual and potential economic growth. Bernanke’s monetarist postulate supports loose monetary policy and massive levels of QE. – H. J. Huney, 2011

To be continued…

| The above data and research was compiled from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither MBMG International Ltd nor its officers can accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the above article nor bear any responsibility for any losses achieved as a result of any actions taken or not taken as a consequence of reading the above article. For more information please contact Graham Macdonald on graham@mbmg-international.com |