In the early hours of 23rd March, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that his father and independent Singapore’s first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, had died.

Lee’s death brought tributes from leaders around the world, including UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and US President Barak Obama. “He was a true giant of history who will be remembered for generations to come as the father of modern Singapore and as one the great strategists of Asian affairs,” President Obama said shortly after the announcement.1

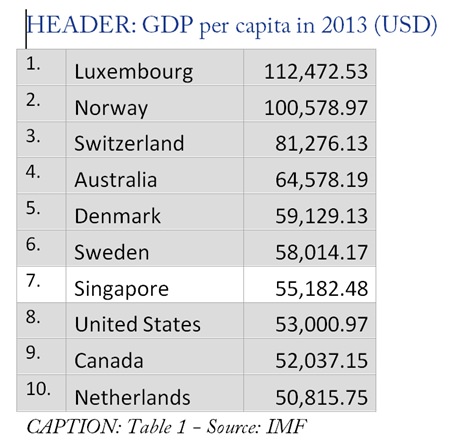

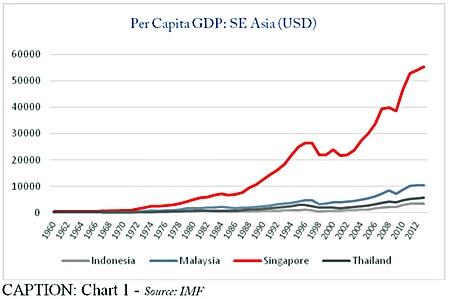

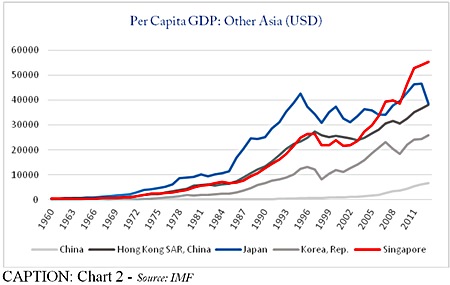

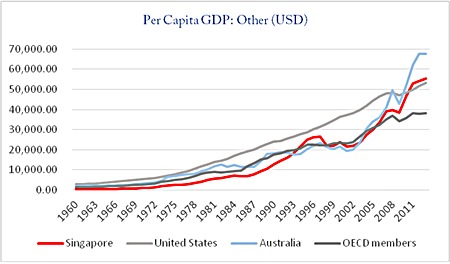

A Cambridge-educated lawyer, Lee is widely credited with building Singapore into one of the world’s wealthiest nations on a per capita basis.2

This was no small feat, given the tumultuous beginnings independent Singapore had to endure.

In the aftermath of World War Two, the island remained a British colony and began a slow process to winning total self-rule. This was finally achieved in 1959, when Lee’s People’s Action Party won an overwhelming majority in elections to the new Legislative Assembly.

Having fulfilled Lee’s objective to enroll Singapore in the newly-formed state of Malaysia in 1963, it became clear that the island’s affiliation to Kuala Lumpur would not work. In August 1965, Lee tearfully announced the dream of unity was over. “For me, it is a moment of anguish. All my life, my whole adult life, I have believed in merger and unity of the two territories,” he said3.

Lee’s government then used Singapore’s independence, geography and its people’s education to create one of the world’s prominent financial centres.

Taking its place on the world stage, Lee strengthened Singapore’s ties with the US and played a key role in the development of ASEAN, forging strong links with Thailand, and the Philippines, in addition to neighbouring Indonesia and Malaysia.

For forty years from 1970, the island-state enjoyed economic growth rates to rival any among the East Asian tigers.4

Lee’s foreign policy transformed ASEAN into a group primarily concerned with trade: freer trade in the region was beneficial to Singapore as a centre of commerce.

After stepping down as Prime Minister in 1990, Lee took on a role as Minister Mentor to his successors – Goh Chok Tong and then his own son – until retirement in 2011. He saw eastern Asian success as the triumph of “Confucian values” (discipline, order and respect) and promoted Singapore as the centre of “Asian values”.5

In a letter of condolence to Lee’s son, Singapore’s president Tony Tan said, “Many doubted if Singapore could survive as a nation but Mr. Lee rallied our people together and led his cabinet colleagues to successfully build up our armed forces, develop our infrastructure and transform Singapore into a global metropolis.”6

One important aspect of Lee’s time in power was investment in education to create a highly-educated workforce, fluent in English. Tan acknowledged that “Establishing English as the common working language enabled Singaporeans to have more equal opportunities to learn, communicate and work regardless of race.

“Because of these policies, Singaporeans today are able to leverage on our bilingual and bicultural edge to take advantage of the opportunities that present themselves around the world,” Tan went on to say.

There can be little doubt that Lee Kuan Yew made Singapore what it is today, one of the major players in the global economy.

Footnotes:

1 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/22/

singapore-lee-kuan-yew-dies-91

2 idem

3 August 9, 1965, as quoted in The Theatre and the State in Singapore: Orthodoxy and Resistance, Terence Chong

4 idem

5 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/22/lee-kuan-yew

6 http://www.hrdmag.com.sg/news/one-of-the-

greatest-leaders-of-the-century-dies-198430.aspx