In summer no less than around 9 million people1 tend to visit Spain for a holiday. With its hot climate, beaches, culture and excellent food, it’s no surprise that it is so popular. However, whilst tourists take in the sun and sangría, daily life for the local people is as hard as it’s been for decades.

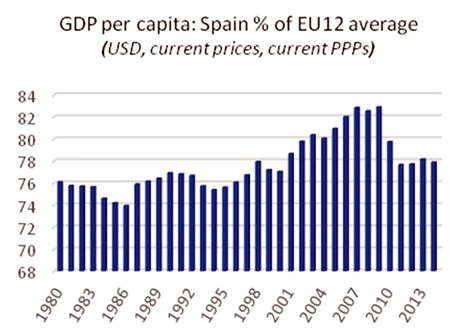

Rising from the ashes of an oppressive dictatorship, Spain became an example of how an EU member could develop. From joining the EEC in 1986, until the global financial crisis hit, Spain’s per capita GDP consistently gained on the EU average (see chart 1).

Chart 1 – Source: OECD.

Chart 1 – Source: OECD.

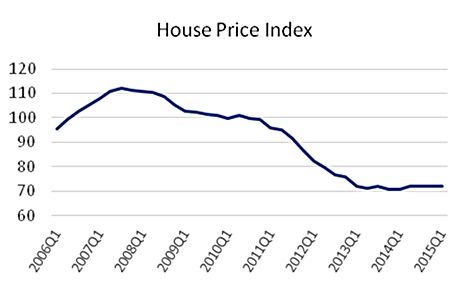

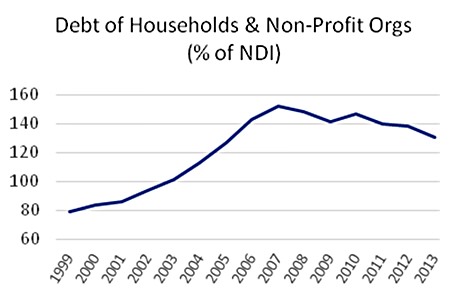

The problem was that, along with the huge investment in infrastructure (by 2011 the country had 69% greater motorway density than in 1996, for example2) came a massive increase in construction: 15 million new buildings and 4.2 million new homes appeared between 2002 and 2011 – representing a 20% increase. What’s more, 15% of those 4.2 million homes were built in 2005-2006 alone.3 With that came a significant rise in house prices and household debt (see charts 2 & 3), as banks offered mortgages of up to 50 years for 100% of the market price.4

Chart 2 – Source: Eurostat

Chart 2 – Source: Eurostat

Then, the height of the Spanish bubble came as the US housing market was about to burst, leading to the global financial crisis (GFC).

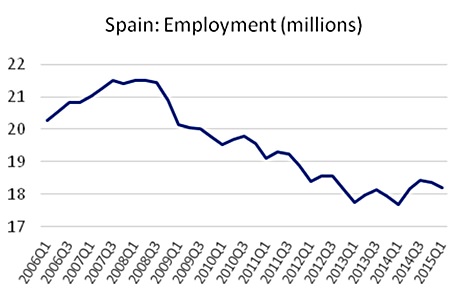

By 2006, the ECB’s base interest rate (EURIBOR) was more than double that of just three years previously.5 As some 94% of mortgages in Spain are based on variable interest rates,6 monthly repayments quickly became much higher at a time when employment figures nosedived (see chart 4).

Chart 4 – Source: Eurostat

Chart 4 – Source: Eurostat

The bubble burst meant that Spanish banks were excessively exposed to toxic property assets – between 2007 and 2013, loan defaults of property developers and construction firms jumped from 0.6% of the total bank lending in these sectors to over 25%. Across all sectors, the non-performing loan ratio went from 0.7% of lending to 13.6% over the same period – that figure doesn’t even include the toxic loans placed in the bad bank SAREB.7

Chart 3 – Source: OECD

Chart 3 – Source: OECD

Loan defaults on houses led to foreclosures, which numbered over 270,000 between Q4 2011 and Q1 20158. When the government intervened in July 2012,9 around half the loans in the Spanish banking system were given out by the regional, unlisted and poorly-regulated savings banks (cajas).10

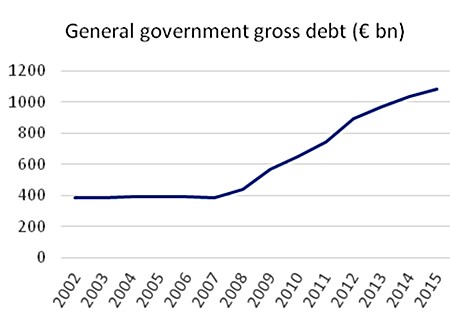

The national government was also adversely affected by the burst: its public debt rose by 133% between 2006 and 2012 – and is still rising today.11 Some of this was down to money used to bail out the banking system. However, the main reason was that government spending had increased significantly between 2000 and 2009.12 This expenditure had been largely covered by revenues from property-related taxation;13 once the bubble burst and people stopped buying houses, government revenues took a hit (see chart 5).

Chart 5 – Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2015

Chart 5 – Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2015

So with a high level of public debt, rising unemployment and a worrying number of foreclosures; what did the government do? Concentrate on its own debt, of course. It announced austerity measures in May 2010 worth 1.5% of GDP and further measures of the next six months’ worth an estimated 5% of GDP in total. These measures included a 2% rise in VAT.14

Unsurprisingly, this policy has done nothing to boost economic activity. GDP has barely recovered, house prices are still low and consumer prices fell by 0.6%, on average, in the first half of 2015.15 Employment statistics have been reduced to ‘good news’ announcements: such as the recent publication of statistics showing 295,600 more people in work in Q2 2015. What was not mentioned in this announcement was that around half of these jobs were in the service sector (i.e. tourism during its peak period) and whether the positions were temporary or permanent.16

Despite the sharp upturn in public debt, the percentage of Spanish public debt to GDP was at under 47% when austerity was announced. By comparison, Greece was at 106% and Germany at 54%. By the end of 2014 Spain’s debt had reached 78%; but then GDP fell by 1% on average between 2009 and 2014,17 so the debt figure is not as dramatic as at first glance.

Also, the recent past has shown that the way to increase government revenue is to encourage a growing economy, not a shrinking one. After all, a government’s budget is not a giant version of an individual’s bank account.

As Prof. Steve Keen, my colleague at IDEA Economics, pointed out in his 2015 Outlook paper,18 if a government runs at a surplus, it means that it’s getting more tax from the private sector. Thus, the private sector is earning less – and therefore likely running up debts – in order to keep the government in surplus. Proof of this in Spain is that private consumption is falling: Q1 year-on-year consumption has dropped by 2.6% between 2006 and 2015.

So it looks like Spain is heading for the debt deflation that has hampered Japan for the last 25 years.19 As with Greece, it is in the Eurozone, so is straight-jacketed regarding monetary policy.

It’s time for austerity to stop before it’s too late: the government of Catalonia, Spain’s richest region, has declared its next elections in late September as a plebiscite on whether it remains part of the kingdom.20 Otherwise before the national government acts, the bell could already have tolled.

Paul Gambles has completed CFA level 1 and is licensed by the SEC as both a Securities Fundamental Investment Analyst and an Investment Planner.

Footnotes:

1 http://economia.elpais.com/economia/2014/09/

22/actualidad/1411372040_587378.html

2 Infrastructure in the EU: Developments and Impact on Growth, European Commission, Occasional Papers 203, December 2014

3 Instituto Nacional de Estadística

4 http://www.expansion.com/2010/08/28/

empresas/banca/1282946807.html

5 European Central Bank

6 http://economia.elpais.com/economia/2014/08/

22/actualidad/1408697674_140579.html

7 William Chislett, Spain’s Banking Crisis: a light in the tunnel, Real Instituto El Cano, 2014.

8 http://elpais.com/elpais/2015/08/01/

media/1438446912 _132166.html

9 http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/assistance_ eu_ms/spain/index_en.htm

10 Willim Chislett, Spain’s Banking Crisis: a light in the tunnel, Real Instituto El Cano, 2014

11 Eurostat

12 IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2015

13 Juan Carlos Hidalgo, Looking at Austerity in Spain, Cato Institute,

http://www.cato.org/blog/looking-austerity-spain

14 Spain’s Economic Crisis: A Timeline, Daily Telegraph, 8th June 2012

15 INE, Spanish National Institute of Statistics

16 http://www.efe.com/efe/america/economia/baja-el-desempleo-

en-295-600-personas-y-sube-empleo-411-800-espana/20000011-2671474

17 Eurostat

18 Steve Keen’s Economic Outlook 2015, http://www.ideaeconomics.org/

19 ibid

20 http://ccaa.elpais.com/ccaa/2015/

08/03/catalunya/1438626621_703380.html

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook: /MBMGGroup |