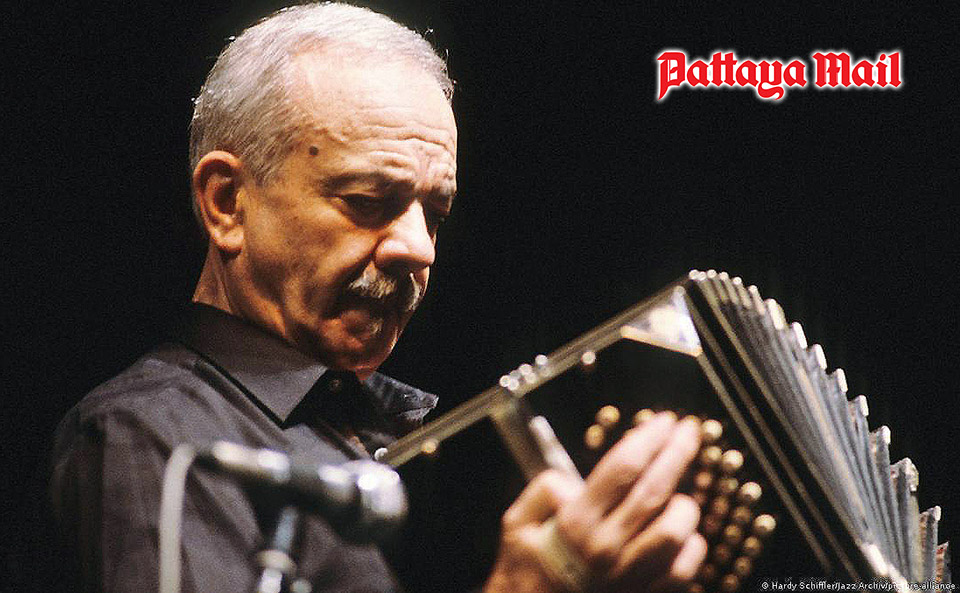

I wonder if you can describe a bandoneón? If you can’t, scroll down and you’ll find a photo of one. It looks like a large square accordion and it’s played by drawing the air through bellows (by pushing and pulling) which causes the internal reeds to vibrate. The air is routed to the individual reeds by buttons at each end of the instrument. Although it resembles an accordion, for technical reasons it’s considered a member of the concertina family. The bandoneón first appeared in the middle of the 19th century. It was a development of the concertina and invented by the German instrument dealer Heinrich Band, who with touching modestly, named the instrument after himself.

During the late 19th century, German and Italian emigrants took bandoneóns to Argentina, where they were enthusiastically adopted into tango music. By the early 20th century, bandoneóns were being produced in Germany solely for sale in Argentina and Uruguay. In 1930, twenty-five thousand of them were shipped to Argentina alone. You may be wondering why I am telling you all this. (The thought had occurred to me. – Ed.)

Well, at Ben’s Theater recently a splendid concert featured not only a Piano Trio by Brahms but also The Four Seasons, a suite of pieces composed by the 20th century Argentinian composer Astor Piazzolla, who – among other things – was a virtuoso bandoneón player. He began playing it at the age of eight, after his father spotted a secondhand one in a New York pawn shop. He wrote his first tango at the age of nine and the following year took music lessons with Béla Wilda, a student of Rachmaninoff. Wilda taught Piazzolla how to play Bach on the bandoneón.

This was the last concert of 2023 at Ben’s Theater and given by Mahakit Lerdcheewanan (violin), Marcin Szawelski (cello) and Suvida Neramit-Aram (piano). They opened the concert with the Piano Trio No. 1 in B major, Op. 8 by the 19th century German composer Johannes Brahms. He completed this impressive work in January 1854 when he was only twenty-one, a staggering feat for one so young. Two months earlier Brahms had met Robert and Clara Schumann for the first time. Schumann was highly impressed with the young composer and referred to him “the young eagle”. However, thirty-five years later during the summer of 1889, the self-critical Brahms returned to the work with the intention of trimming what he described as “youthful excesses.” In September that year, he wrote to Clara Schumann, “You cannot imagine how I trifled away the lovely summer. I have rewritten my B major Trio and can now call it Op 108 instead of Op 8. It will not be so dreary as before, but will it be better?”

Although Brahms made extensive changes and reduced the first movement to half its original length, he didn’t change the wonderful opening theme, an expansive heart-warming melody. It’s one of his most memorable tunes and has a passing resemblance to the main theme in the last movement of his First Symphony. This opening section sounded magnificent, and Marcin’s superb luminous cello tone was remarkably beautiful. Later, the violin takes up the melody which Mahakit played to perfection. The entire opening section was one the highlights of the concert with impeccable playing from all three musicians. The middle section has many reminders of Beethoven and the musicians created a magic moment near the end of the movement with the pianissimo passage.

The scherzo (skert–soh) second movement was beautifully light and graceful with some especially sensitive string playing. The “trio” section, which is the central part of the movement, was particularly successful with exquisite playing from pianist Suvida Neramit-Aram. Brahms transforms the original opening phrase into a captivating waltz-like melody and the players brought forward the beautiful lilting rhythms. The return to the scherzo was especially commendable, with lively string articulation and a perfect ending to the movement.

The third movement, marked Adagio (very slow) opens with a spacious, solemn hymn-like melody on the piano answered by the strings. Suvida brought out the sense of wonderment in the music and both Mahakit and Marcin played with great sensitivity. The beautiful and poignant cello solo in this movement was superbly played (as usual) by Marcin with his fabulous singing tone and his perceptive sense of phrase and line.

The finale opens with another cello melody, this time with a rather dark Hungarian flavour. The musicians brought a compelling sense of urgency to the melody. This movement is full of restless, ominous music and was given a powerful performance, especially Suvida who played with drive and passion. It was rightly, a power-house performance marred only by occasional moments of weak ensemble. At times, the violin and piano were simply not together but this may have been because the violinist could not see the pianist and direct eye-contact was impossible. Nevertheless, I was impressed by Suvida’s remarkably competent performance, though at times the piano tended to dominate.

Violinist Mahakit Lerdcheewanan is on the staff at the College of Music, Mahidol University and is the Assistant Concertmaster (or Deputy Leader, as they say in Britain) of the Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra. He has also performed in the United States and was concertmaster for the TPO during its 2022 tour of Europe. Marcin Szawelski is from Gdańsk in Poland and he’s the Principal Cello with the TPO. He began his musical training at age seven and later earned a Master of Arts in Cello Performance from Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music. He currently teaches cello and chamber music at the College of Music, Mahidol University and has written two textbooks for cellists.

Pianist Suvida Neramit-Aram studied with Thailand’s foremost piano teachers and completed her Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance from Lynn University. Suvida, a Master of Music at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music and a Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance at the University of Texas. Suvida has performed at London’s Royal Albert Hall and at the Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall.

The second half of the concert featured a performance of Astor Piazzolla’s suite Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas (“The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires”) which was composed at various times during the 1960s. The work consists of four tango-style pieces originally conceived as separate compositions though today they are usually played together as a suite. The Spanish word porteño (pohr-teh-nyoh) refers to someone born in Buenos Aires.

The tango originated in the 1880s in Argentina and Uruguay and was immensely popular in bars and various places of ill-repute. But Piazzolla – with his special kind of genius – brought the tango to new heights; no longer a simple dance but a powerful and complex expressive form that evokes the soul of Argentina. The pianist Arthur Rubinstein advised Piazzolla to seek tuition from Alberto Ginastera, Argentina’s leading composer and to study the scores of music by Stravinsky, Bartók and Ravel. All this influenced the new sophisticated tango style which was called nuevo tango, and it incorporated elements from jazz and classical music. The Four Seasons was originally scored for Piazzolla’s own quintet of violin, piano, electric guitar, double bass and of course, bandoneón.

This compelling and attractive music became so popular that over the years, it has been arranged for different ensembles. Piazzolla’s music is often dark and sombre, using minor keys and sudden changes of mood. Dreamy lyrical passages are contrasted with others which are melodramatic and intensely rhythmic, dominated by the infectious rhythms and flavour of the tango.

It seemed to me that Mahakit, Marcin and Suvida really caught the essence of this sultry and brooding music. The playing seemed more secure and there was a much greater sense of ensemble. In the first movement, the musicians captured the warm, exotic flavour and in the second movement, I was particularly impressed with the string playing and the way they dealt with the dynamic, theatrical ending. In the third movement, the cello solo from Marcin was beautifully phrased and the harmonics in the top register sounded magical. I thought that Mahakit’s violin playing was particularly expressive in this movement and brought a sense of timelessness, before the jazzy coda took the movement to a close. It was brilliantly played.

The last movement (Winter) opened with beautifully expressive playing from Suvida. The cello solo (yes, another cello solo) from Marcin was perfection itself, as was the sensitive accompaniment to the following violin solo. The movement ended with an affectionate glance back to the music of the Baroque with echoes of Pachelbel and the original Four Seasons composed by Vivaldi. It made a compelling end to an excellent and musically exciting concert.

Incidentally, we must thank the legendary and slightly daunting French teacher Nadia Boulanger for The Four Seasons. Among her students were many world-class musicians including Daniel Barenboim, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, John Eliot Gardiner, Philip Glass, Roy Harris and Quincy Jones to name but a handful. Piazzolla was on the point of abandoning his tango-style music altogether, preferring to regard himself as a “classical” composer. In 1953, he went to study with Boulanger. He presented her with several of his classically-inspired compositions but she felt the music didn’t have a personal quality. Piazzolla finally admitted that he played bandoneón and wrote tangos. Then he played for her a tango piece he had written earlier. Nadio Boulanger told Piazzolla to throw away his “classical” compositions. Pointing to the tango manuscript she exclaimed, ‘There is Piazzolla! Never leave it!”. And he didn’t.