Yesterday I was making some final corrections to a choral arrangement I’ve been writing recently and my thoughts drifted towards what the first choral music must have sounded like. There’s no way of knowing, of course. These days one instinctively goes to the computer to start a search of online articles but unusually, the computer had been switched off during a sudden thunderstorm. The next best option was to dig out my copy of the Oxford Companion to Music, an enormous tome of 1,400 pages with many fascinating articles.

Oddly enough, this distinguished volume contained little about the earliest choral music. But I’d guess that its history reaches back beyond recorded time. Perhaps humans initially made vocal sounds together in the form of shouting to scare away unwanted predatory animals. This might have been one of the earliest examples of people making using their voices together, unpleasant though they might have sounded. At some point in human evolution, perhaps even before recognizable speech began to develop, people discovered that they could also sing.

Countless centuries were to elapse before anything we would recognise as choral music appeared. The nearest thing to a western choir emerged in ancient Greece around the second century BC in the form of the chorus for Greek dramas. Choral singing in the form of simple chants was fostered in the Christian church. Chants that eventually known as Gregorian Chant consisted of a single melodic line and nothing else. Many examples of these strangely beautiful melodies still exist. The twelfth century French composers Léonin and Pérotin developed a choral style at Notre Dame in Paris known as organum in which the tenor singers held the chant melody, while the lower voices provided a sustained drone-like bass line. Incidentally, the word “tenor” derives from the Latin, tenere meaning “to hold”. I bet you didn’t know that.

By the Renaissance (roughly between 1400 and 1600) choral music was well-established and had become sophisticated in its use of voices and harmonies. Secular choral music – especially madrigals – began to appear, thanks largely to the invention of printing. Choral music flourished during the Baroque and in a way has rarely faded from popularity, for the concept of people singing together is a part of many different cultures.

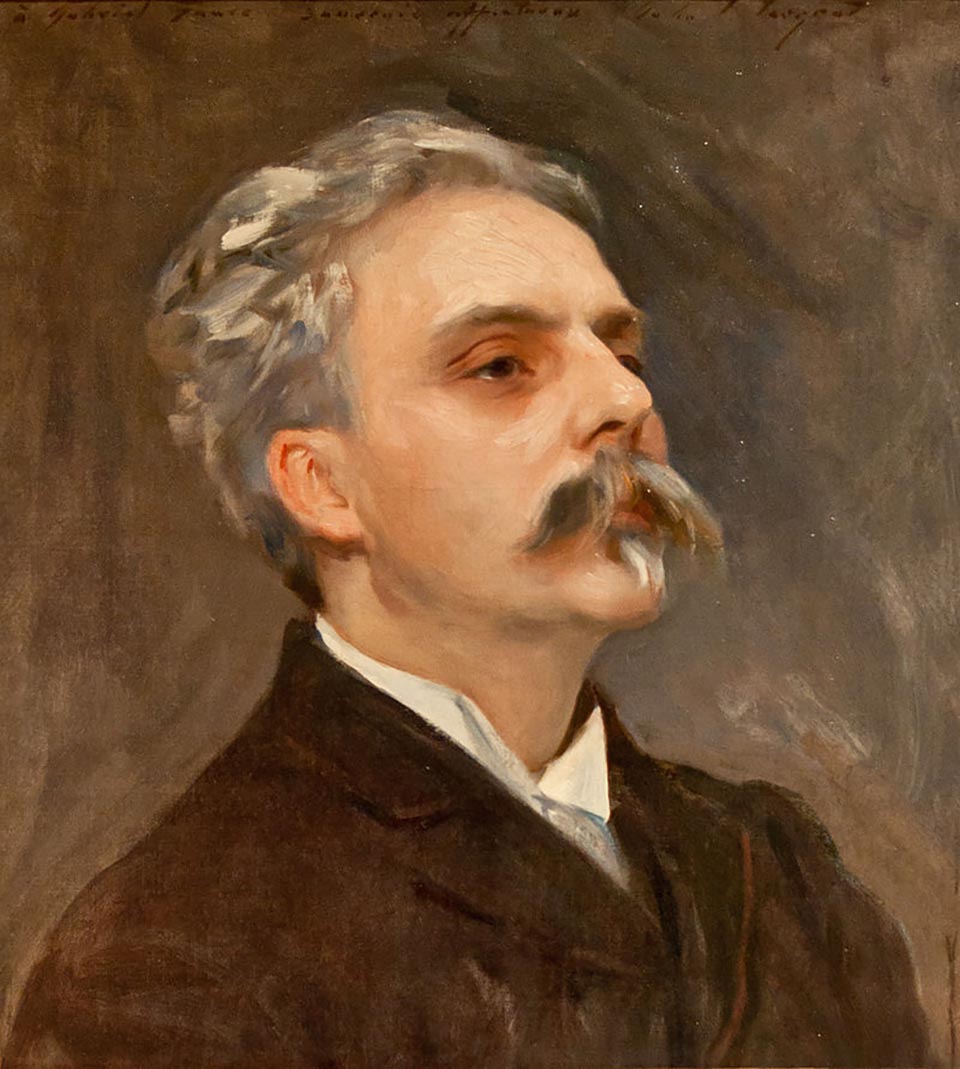

Years ago, as a student, I discovered a lovely choral piece by the French composer Gabriel Fauré (Gah-bree-ell Fo-ray). It was his Requiem Op 48 and I acquired a much-loved 1960s recording by King’s College Choir when it was at its peak. At the time. the music was a revelation to me, because along with captivating melodies, Fauré often used daring harmonies and unexpected changes of key.

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924): Requiem, Op. 48. Laurence Guillod (sop), Thomas Tatzl (bar), Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir cond. James Gaffigan (Duration: 39:11, Video: 1080p HD)

The work was composed during the late 1880s, revised in the 1890s and finally completed in 1900. Strangely enough, no one knows exactly why Fauré composed this work, though there has been much speculation. Some writers suggest that it was almost certainly a musical tribute to his father, who died in 1885. However, the composer himself said in a letter to a friend, “it wasn’t written for anything – for pleasure, if I may call it that.” Fauré was a religious sceptic and wrote, “Everything I managed to entertain by way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem, which moreover is dominated from beginning to end by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest.”

Gabriel Fauré was born in Pamiers, a lovely old town in southwestern France about 45 miles south of Toulouse. His musical talent began to show when he was a boy. In adult life he wrote, “I grew up, a rather quiet, well-behaved child in an area of great beauty but the only thing I remember really clearly is the harmonium in the little chapel. Every time I could get away, I ran there…I played atrociously…but I do remember that I was happy.” At the age of nine, the young Gabriel was packed off to Paris to study the organ and indeed became a renowned organist as well as a respected composer.

The requiem of course, is traditionally a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased people. Perhaps because Fauré has no religious beliefs, his requiem is quite different in outlook from many that were written by other composers. It is more of a concert piece than liturgical music. The music is calm, reflective and lyrical and full of beautiful melodies. It’s cast in seven sections, but the most popular movements are the Sanctus (15:11) Pie Jesu (18:46) and In Paradisum (32:08). I’m not going to go into technical details about the work, because there’s an excellent and detailed analysis of it at Wikipedia.

Fauré scored the Requiem for two soloists, chorus and orchestra and the vocal writing is fascinating, because sometimes the choir sings in union, at other times Fauré uses rich choral harmonies by dividing the tenor and bass sections. The ethereal last movement, In paradisum is stunningly beautiful and fittingly, the work was performed at Fauré’s own funeral in 1924.