Now then, what were you doing in 1956? I suppose if you are under the age of sixty-five your answer will probably be “not a lot”. Well, I have to admit that in 1956 I was a very small boy but not a particularly distinguished one. I was a passable pianist, though my mother was far better. I did a bit of composing and played the cello in our local orchestra which used to meet every Wednesday evening. We didn’t have a television in those days because nobody did. At least, not on the British island where we lived because it was too far from the transmitter. The radio was the sole means of receiving sounds from the outside world.

My parents listened to the BBC’s quaintly-named Home Service (later re-named Radio 4) but I liked the BBC Third Programme (later Radio 3) for classical music and Radio Luxembourg for popular music. My father was somewhat dismissive of Radio Luxembourg but to me it seemed exotic and glamorously remote, broadcasting from a tiny country (actually a Grand Duchy) near the heart of Europe. Not until many years later was I to discover to my disappointment that many of the programmes were pre-recorded in London.

In 1956, Radio Luxembourg started playing Perry Como’s hit song Hot Diggity a merry melody if ever there was one, but with absurdly childish lyrics. I soon discovered that the song had taken the two main melodies of an orchestral piece entitled España by Emmanuel Chabrier. Yesterday, I checked the origins of the song online and discovered that two song-writers are credited. Two song writers? It seems extraordinary that two people were necessary to invent the vacuous and half-baked lyrics when the melody had already been brazenly stolen from someone else. Daylight robbery, if you ask me.

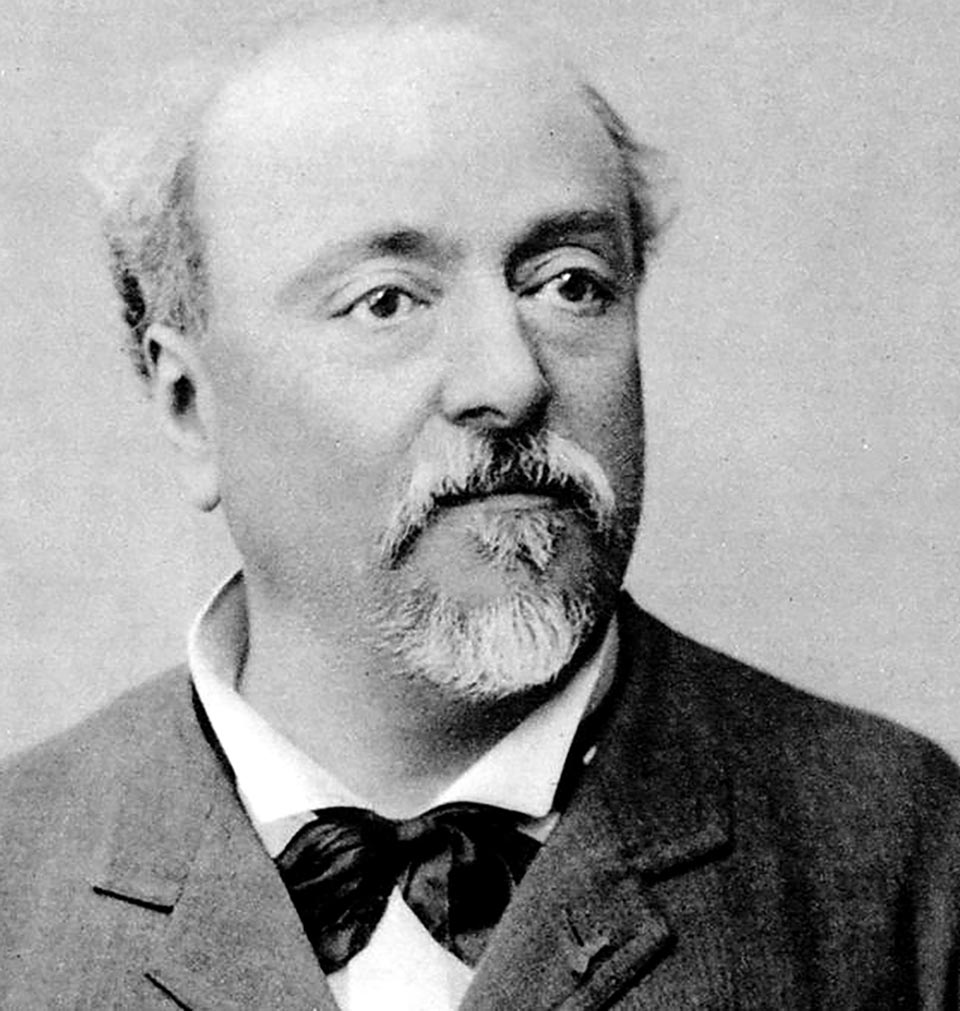

Chabrier was a French composer and pianist known today for just a handful of pieces. As a teenager, he became attracted to music and painting but his bourgeois parents didn’t approve of an artistic career so he was packed off to Paris to study law. While there, he also studied piano and music theory although he never had formal tuition in composing. He eventually got a job as a civil servant while immersing himself in the artistic life of Paris. He eventually became a full-time composer but being self-taught gave him the freedom to create his own musical language, undaunted by established conventions.

This colourful and evocative piece is Chabrier’s most well-known composition. You’ll almost certainly recognise the melodies if you’ve never heard the work before. In 1882, Chabrier and his wife toured Spain and visited all the major cities from Barcelona in the north to Málaga in the south. One of the letters he wrote during the tour states that on his return to Paris, he would compose, “an extraordinary fantasia which would incite the audience to a pitch of excitement.”

And he did just that. España was originally written for piano duet but later brilliantly orchestrated by the composer. It was encored at its first performance and well-received by the critics, bringing overnight fame to Chabrier. Even Gustav Mahler later declared it to be “the start of modern music”. Today the work falls easily on the ear and it’s full of delightful melodies and Iberian rhythms. It’s even more impressive when we remember that the composer was self-taught. This video is streamed in ultra-high definition, so you’ll need a pretty fast connection to see it at maximum resolution.

Emmanuel Chabrier: Suite Pastorale. Philharmonic Orchestra of Radio France cond. John Eliot Gardiner (Duration: 20:49; Video: 1080p HD)

Like España, this work also began life as music for piano, in this case a suite of ten pieces entitled Pièces Pittoresques (“Picturesque pieces”), written in 1880 while the composer was on a convalescent holiday in Normandy. Chabrier later arranged four of the pieces for orchestra and renamed the new incarnation Suite Pastorale. The movements are entitled, Idylle, Danse Villageoise, Sous-bois and Scherzo-valse. Incidentally, Sous-bois means “under the trees” but I don’t suppose the other titles require translation.

The work begins unusually with a solo for the triangle: just three quiet notes. If your hearing is a bit dodgy, you might not hear them at all. Then comes a lyrical flute solo over pizzicato strings, with lovely transparent woodwind writing. The Danse Villageoise is somewhat gentrified with light and effective woodwind and brass writing. The third movement is a wonderfully atmospheric piece and with shifting chromatic harmonies that seem to anticipate the music of Ravel. The spirited last movement starts out as a lively waltz but the pastoral mood is never far away and there are some lovely delicately scored passages. This accomplished music makes one wonder why Chabrier’s work is so neglected these days. C’est la vie, I suppose.