And that’s another thing. One of the few aspects of British life that I miss are the crisp spring mornings, the Sunday Times, the Chinese take-aways and the daffodils. And the country lanes. I used to delight in pottering along those quiet little roads; the sort with overgrown grey stone walls on either side and a strip of uncut grass meandering down the middle. Sometimes, I would drive down an inviting lane just to see where it went, to discover eventually that it led to a muddy farmyard.

Michael McCarthy wrote, “Britishness as a cultural identity has become surrounded by doubts and misgivings in recent years…yet it is clear…that a sense of Britishness stubbornly persists in millions of people and that a very prominent component of this is a feeling for the countryside”. The countryside, he explains, “is regarded as not merely an alternative to, or escape from the town but that the landscape is seen as special, even unique, in itself: the unthreatening mix of the farmed and the wild, which is pretty and charming, rather than grandiose and magnificent.” It’s not surprising that one of the best-loved national songs refers to “England’s green and pleasant land”.

Some years ago, Britain’s National Trust organized a survey to find the nation’s favourite poem about the “great British countryside”. The short-list included works by Thomas Hardy, Christina Rossetti, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Alexander Pope and Robert Bloomfield. Many of the poems speak of days of long ago, such as the lovely but fairly typical lines from Elizabeth Barret Browning: “Hills, vales, woods, netted in a silver mist, Farm, granges, doubled up among the hills, And cattle grazing in the watered vales, And cottage-chimneys smoking from the woods.”

In his superb book The English: Portrait of a People, Jeremy Paxman writes, “In World War One, soldiers were dispatched to the Front from towns and cities throughout Britain. Their loved ones sent them postcards showing churches, fields and gardens, above all, villages. This, the unstated message went, is what you are fighting for.”

Gerald Finzi (1901-1956): Eclogue in F major Op. 10. Roberto Plano (pno), Nuova Orchestra da Camera Ferruccio Busoni cond. Massimo Belli. (Duration: 12:25; Video: 1080p HD)

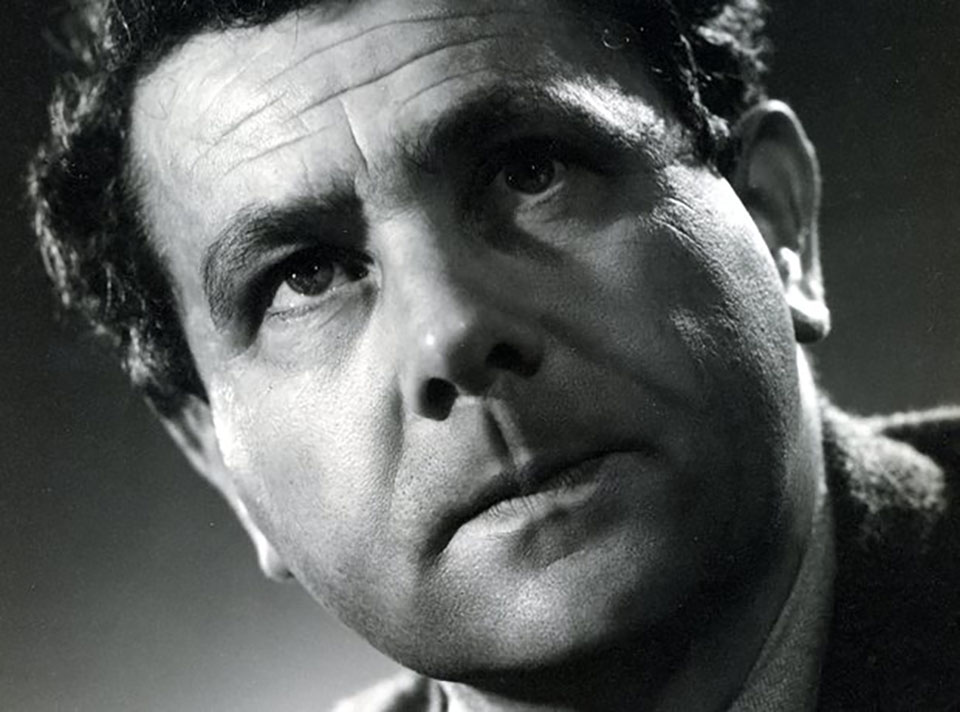

Gerald Finzi would have appreciated the bucolic picture painted by Elizabeth Barret Browning. Although his music is neglected today, he became one of the most characteristically “English” composers of his generation. When he was a boy, his father died just before Gerald’s eighth birthday and during his formative years, he suffered the loss of all three of his brothers, events that contributed to his somewhat melancholy outlook on life. He found solace in the poetry of Thomas Hardy and Christina Rossetti and later set some of their poems to music.

This curiously titled work dates from the late 1920s, around the same time he was writing his Grand Fantasia and Toccata for piano and orchestra. It was evidently intended to be part of a piano concerto which never materialized. The ancient word “eclogue” comes from Middle English eclog which in turn originates in the Latin ecloga. By the seventeenth century, the word had come to mean pastoral poems about rural life and indeed Finzi’s piece is a celebration of the English landscape. It’s a remarkably beautiful and melancholy one-movement work for piano and strings. The composer reworked it twice but oddly enough it wasn’t published or performed until 1957, a year after his death.

George Butterworth (1885-1916): The Banks of Green Willow. Portland Youth Philharmonic, cond. David Hattner. (Duration: 06:35; Video: 1080p HD)

This is Butterworth’s best-known work, another pastoral piece that evokes the atmosphere of the English countryside. Composed in 1913 for small orchestra, it’s a companion piece for Two English Idylls that Butterworth had completed a couple of years earlier. All three works are based on English folk songs that the composer came across in Sussex. He made many trips to rural areas in search of folk songs and eventually collected over four hundred of them. The Banks of Green Willow was the last work that he wrote and the last of his own music that he heard, when his friend Adrian Boult conducted the first performance in 1914.

Butterworth would have probably become a composer of international standing had his life not been cut short during the First World War. His bravery in the trenches had already earned him a Military Cross. At the time, the Battle of the Somme was raging and in August 1916 amid fierce fighting, Butterworth was shot dead by a sniper. His body was hastily buried at the side of a trench but was never recovered.

And in case you are wondering about the line Meadowsweet, and haycocks dry, it comes from an evocative yet deceptively simple short poem entitled “Adlestrop” written in 1914 by Edward Thomas, a contemporary of Butterworth. He was best known for his poetical depictions of rural England. Sadly, he too was killed in action during the First World War; in 1917 at the Battle of Arras, soon after his arrival in France.